Settler societies depend on the continuous to accumulate resources and dispose natives from their means of life by uprooting any productive or sentimental relationship with their land. Landcentrism methodically acts for maintaining the permanency of settler societies, as control of land aligns with control over the conditions of survival. The territory targeted for colonial settlement is seen as “free land”, with no regard to existing communities.

Settler-colonialism is the systematic process of transforming territory by control over land, resources and inhabitants to establish a new permanent and exclusive political entity with a society that replaces, exploits and coerces indigenous spaces of livelihood.

In the case of Zionism, the objective was (and still is) to create an ethno-exclusive settler society on through “nativizing” the settler-immigrant society. This has been carried out through the drawing historical continuums between the land and the settlers by evoking biblio-religious discourses accompanied by a process of “memoricide”, the complete erasure of native histories and the construction of new settler histories. Crucially, the act of immigration to Palestine was termed as “return” to “the promised land”, biblically “Aliya”: the name given to the waves of Jewish immigration to Palestine.

As the sociologist Baruch Kimmerling wrote[1], “every bit of land which passed into the control of Jews, at least until 1947, was in the possession of someone else before they acquired it”. The economic price to be paid for land ownership and settlement was managed and acquired, mainly, by the Jewish National Fund (JNF), an organization that fulfilled the objectives of land acquisition discussed in the First Zionist conference. Through cultivation, Zionism realized the two pivotal pillars of settler-colonialism; territorial control through the appropriation of native land, and the establishment of a new social and political community. It played an important ideological role for Zionism; attracting further Jewish settler-immigration by creating demand for labor, food, housing, and a sense of community – resources that are vital for the formation of a national collective. It also fabricated a connection between the settlers and the land, necessitating a presence in, maintenance of, and later, sovereignty over land.

Cultivation is the operational extension of the Zionist myth of “making the desert bloom” reiterated in the Declaration of Independence and in the statements of numerous Israeli Prime Minsters. Settler-immigration to cultivable lands ideally located in close proximity to water resources was justified through the lens of modernization and civilization. It depends on the assumption that when the natives did “exist”, they mismanaged land (and water) and hence the white, modern settler can “unleash the true potential of the land” and “tame nature for the service of humanity”. This stems from the colonial-imperial logic that classifies the natives as inferior and barbaric and the settlers as superior and intelligent.

Hydro-Bordering: Between Imperialism, Occupation and Invasion

Pre-Nakba/State Period

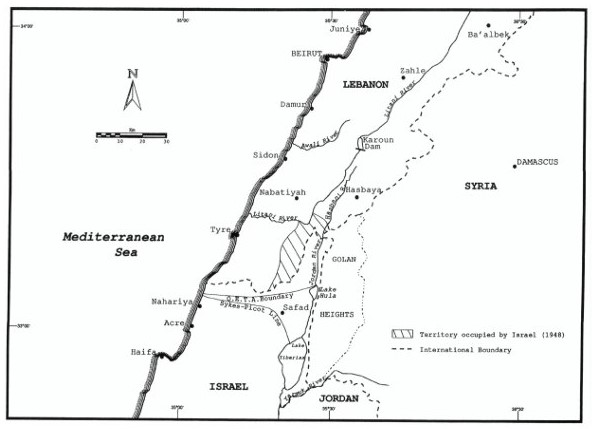

The area that encases Palestine was ruled by the Ottoman empire until its fall after the First World War. British, French, Italian and Russian officials engaged in secret talks to divide the area. These talks resulted in the Sykes-Picot agreement of 1916 establishing systems of mandate and direct governance in the ‘fertile crescent’, portions of Hejaz, Turkey, up till Mount Ararat. Imperial boundary making in the Levant is a direct consequence of the logic of unmaking/making of “productive” colonial spaces – something that coincided with Zionist aspirations. However, under this framework the majority of Palestine was allocated as an international zone. The northern boundary of Palestine at that time extended from a point just about Nahariya to a North-Western point on Lake Tabariya/Tiberias. The Balfour declaration challenged this arrangement in 1917. It was a written promise from the British government to Lord Rothschild to aid in the establishment of a “national home” for Jews in Palestine, that actually meant the British interests aligned with Zionist interests.

The Zionists’ aspirations in the Northern water were pronounced by the British in the 1920 British-Franco discussions where the former requested to expand the mandate boundaries to engulf the entire Jordan basin from the Mettula settlement [al Mattaleh] northward and eastward down to the Banias springs and the town of Quneitra, well in the territory of the French mandate. In return, the French received the right of direct governance in all of Syria and Lebanon, negating Sykes-Picot and killing any aspiration of independent Arab state. The parties compromised where unto all Jewish settlements in the North went under the British mandate in preparation for the Zionist takeover of the land, and the Golan Heights went under the French mandate. This was signed in 1923 between Colonel Paulet, French, and Colonel Newcombe, British.

Following the Palestinian peasantry’s revolts of 1936, the Peel commission presented the first partition proposal of mandatory Palestine. It divided the territory between a proposed Jewish state, Arab state and a British mandate zone; proposing a population transfer. The boundary drawn allocated the waterrich Northern districts and half of the Western coast to the Jewish state while the Arab state would get the lower half of the coast and the Southern desert and the majority of the Eastern frontier (Downstream Jordan river position). Jerusalem and Tel Aviv would remain under the British mandate. This proposal was rejected by both the Zionists and the Palestinian.

With increasing tensions and the horrors of the Second World War against the Jewish population of Europe, the League of Nations proposed the 1947 partition of Palestine, allocating more than half of the territory for a Jewish state. This was also rejected and ended in the 1948 war. Palestinians were expelled from their homes in what was known as the Nakba (catastrophe) and the Zionists declared the establishment of an Israeli state on the land evicted and claimed by their forces.

Post-Nakba/State Period

After the Zionist movement successfully managed to lobby the British and French mandates to include the fertile Upper Galilee and Hulla mars hes (known as Jorat al Thahab) in Mandate Palestine, the Israeli leaders were aiming for further territorial expansion. Operation Hiram was launched by the Israeli army occupying 18 villages on the Litani river elbow. Israel managed to cut a 2,000 dunams (2 km²) from Lebanese territories into its side of the Armistice frontier formulated in March 1949. Early on Israel trespassed on all three Armistice agreements and was eager to establish its position as a territorial maximizing hydro-hegemony. Israel was keen on controlling the Wadi Araba aquifers and mineral rich riverbeds, it established agricultural settlements well inside Jordanian territory in 1951 extending East of the line by 320 km², and occupying the Jisr al Majame’/al Baqoura area on the Yarmouk triangle. Further, Israel began operating its National Water Carrier project in the demilitarized zone North of Tiberias [Tabariya], a clear breach of the terms of peace with Syria.

To try to alleviate the “tensions”, the Americans proposed the Main Plan under the Johnston negotiations of 1953, to which Israel presented a counter-plan under the name of the Cotton Plan. Israel’s plan included diverting the Litani river water to the Hasabani river to be pumped into Tiberias [Tabariya] for pumping into the National Carrier. The plans failed with the rejection of the Arab league and Ben Gurion’s ascending to power. As Israel was completing its aggressive Carrier project depriving the riparian states from large water flows, the Arab Summit on 1964 recommended an Arab diversion plan to counter Israeli hydro-hegemony.

Failures of the Arab projects combined with the 1967 war meant that Israeli leaders no longer had to hide territorial expansionary plans. Israel invaded the Golan Heights, Cheba’ farms, and the West Bank that year. In doing so, Israel extended its control into the whole of the upper Jordan basin tributaries. The official map of the State of Israel published by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs does not recognize the West Bank and the Golan Heights as occupied territory and extends its international borders to their Eastern edges. The Golan is a hydro-strategic area and constitutes one third of Israel’s fresh water consumption. Controlling the Golan meant controlling Mount Sheikh/Hermon, a central aim for early Zionist hydro-politics. Further, occupation deprived Syria from its water share of the Jordan river basin.

Since then, Israel has been practicing full water control and depriving Syrian farmers from welling or accessing a portion of what is being accessed by Israeli settler farmers.

The invasion of South Lebanon 1978, operation Litani (named after the river!), followed by the occupation of 1982, and 2006 invasion were justified with security concerns. However, there is considerable doubt that ambitions in the Litani and Wazzani were indeed part and parcel of the aggressions.

The peace treaty with Jordan in 1994 gave rise to forms of hydro-hegemonic practices in negotiations. Firstly, the lands of Wadi Araba where Israeli settlements were built were demarcated under the Israeli territory. In return, Israel exchanged rocky lands, unfit for agriculture, to fall under Jordanian sovereignty. When viewing the satellite map of the region, one can see how all the riverbeds and springs, previously in the Jordanian territory were allocated to Israeli sovereignty (I name Wiba/Yahev springs, Paran, Arava, Shilhav and Shivya riverbeds).

Secondly, Article Four of Annex Two of the treaty explicitly mentions the right for Israel to continue using the water from wells drilled in the Jordanian side of Wadi Araba and request further water supplies under the veil of the Joint Water committee. Two occupied regions, al Baqoura/Nahariyam and al Ghamr/Tzofar remained under full Israeli control (in a ‘special regime’) for 25 years, where Israelis had unrestricted access to Jordanian water flows. Jordan was able to practice its sovereignty over these locations since november 2019.

Power imbalance

Concluding, I have attempted to put current Israeli spatial aggressions in the larger history of Zionist thought. What this study showed was the centrality of water in Zionist and Israeli bordering, a process that thrives on extending state control for maximum control over water resources. Israel is a settler-colonial state premised on hydro-territorialization whether through lobbying, negotiating or overt use of force.

I recognized the power imbalance and hence rejected the assumption that Israel is an equal actor in water conflicts, but rather as a hegemonic force historically and systematically appropriating land and water in Palestine and the region. The Zionist ambitions in extending the borders of the “future” state to the whole of Golan and Southern Lebanon materialized shortly after the state’s inception with total disregard to international laws. This was followed by practicing hydro-hegemony for the Jordan river basin and denying the shares of riparian states.

[1] Baruch Kimmerling, 1983. Zionism and territory: The socio-territorial dimensions of Zionist politics. University of California.

_____

Rama Sabanekh is a journalist and researcher. She writes on political economy, geography and violence in the Middle East. This article is a short version of the paper “Understanding Israeli Boundaries As Hydro-territorial: A Study In Zionist History And Practice”, presented for a King’s College London discipline.