With every passing day, we see digital technologies become an even bigger part of our everyday lives, our work, and our relationship with the environment and other people around us. These technologies are the products of big transnational corporations, which actually make a profit from these changes in our routines, from increasingly precarious and controlled work, and from the exploitation of nature—both as raw materials and as source of data.

Social movements that organize to change the logic of production, reproduction, and consumption in societies are tasked with understanding how these companies operate in the different sectors of the economy. “The challenge for those who dare to change the world is to construct a collective and objective analysis about the role of digital data and technology companies in contemporary capitalism,” the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research argues in its dossier Big Tech and the Current Challenges Facing the Class Struggle.

Dismantling the power of transnational corporations. Challenging free trade and its false solutions. Denouncing the logic of accumulation and exploitation that guide capitalist, patriarchal, and racist digitalization. Standing up for technology sovereignty and food sovereignty. These are some of the strategies to struggle for a society that will be centered around the sustainability of life.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, we increasingly observe the issue of digitalization in our everyday lives and across big production chains. We have seen it as we need digital devices to study and work; as precarious jobs on digital platforms grow; as land conflicts and digital surveillance rise, promoted by agribusiness. This is why Tricontinental uses the term CoronaShock, to demonstrate “the incapacity of the bourgeois state to prevent a health and social catastrophe while the social order in the socialist parts of the world appeared much more resilient.”

To encourage a continuous debate on data and technology on the agenda of grassroots and feminist organizations, we share below the excerpt “Big Tech against Nature,” from dossier #46 of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. The dossier is available in English, Spanish, Portuguese, and Greek, and aims to contribute to “analysing how these technologies work as part of the dynamic of capital accumulation.” Read the excerpt below:

*

Big Tech against Nature

If, on the one hand, CoronaShock limited the movement of people and commodities and produced ruptures in global value chains due to problems in the import and export of commodities, on the other hand, it accelerated the demand for digitalisation. It also led to a deeper application of technology to the industrial base and to the mode of production and distribution, both in urban industries and in extractive and agricultural industries, and it deepened the non-separation of working and non-working time, productive and reproductive labour, and spaces of labour and leisure.

In agribusiness, there was a growth in mergers, acquisitions, and deals between agricultural giants, technology giants, and these fintechs. This new infrastructure has resulted in a reorganisation of these actors, a movement which tends, over time, to lead to oligopoly. Such a reorganisation increases the need for massive data-capture in practically all the stages of the agribusiness chain. Moreover, it deepens the precarisation of public services by decreasing the availability of public information while increasing the supply of private platforms and Big Tech infrastructures for public services. This clearly interferes with the process of governments being able to make decisions in their countries.

The companies John Deere and Bosch are hegemonic in the area of tractors and machinery, while in logistics and sales, Cargill, Archer Daniels, Louis Dreyfus, and Bunge dominate. Then there are the big retailers: Walmart, Alibaba, and Amazon, among others.

Technology giants tend to migrate to the agricultural sector with a sort of vertical integration taking place not among companies of the same sector, but along the value chain, which shows the capacity of these companies to absorb and reorganise the chain vertically from the field to the consumer.

There are also tendencies towards the digitalisation of the planet in the realm of natural landscapes and resources as much as in the realm of genetic sequencing. For example, Microsoft is working in partnership with germplasm centres around the world to provide the infrastructure to digitalise these genetic banks. In 2018 at a World Economic Forum meeting at Davos, the Amazon Data Bank project was launched, aiming to catalogue and patent information relating to the genetic sequencing of seeds, seedlings, animals, and a variety of unicellular organisms on earth. This is merely the first step in the Earth Bank of Codes programme.

An oligopolistic market with colonial characteristics is emerging: transnational corporations, mainly domiciled in the Global North, always grant themselves patents and intellectual property rights, which have long invested in science and technology at the cost of extracting low value-added raw materials in the countries of the Global South. Moreover, this technological leap also entails a greater demand for other mineral and energy raw materials (lithium, iron, copper, and rare earth metals, for example), driving towards a more aggressive organisation of the international division of labour to guarantee their supply. In Bolivia, for example, the 2019 coup was directly related to the nationalisation of its lithium reserves, one of the largest in the world.

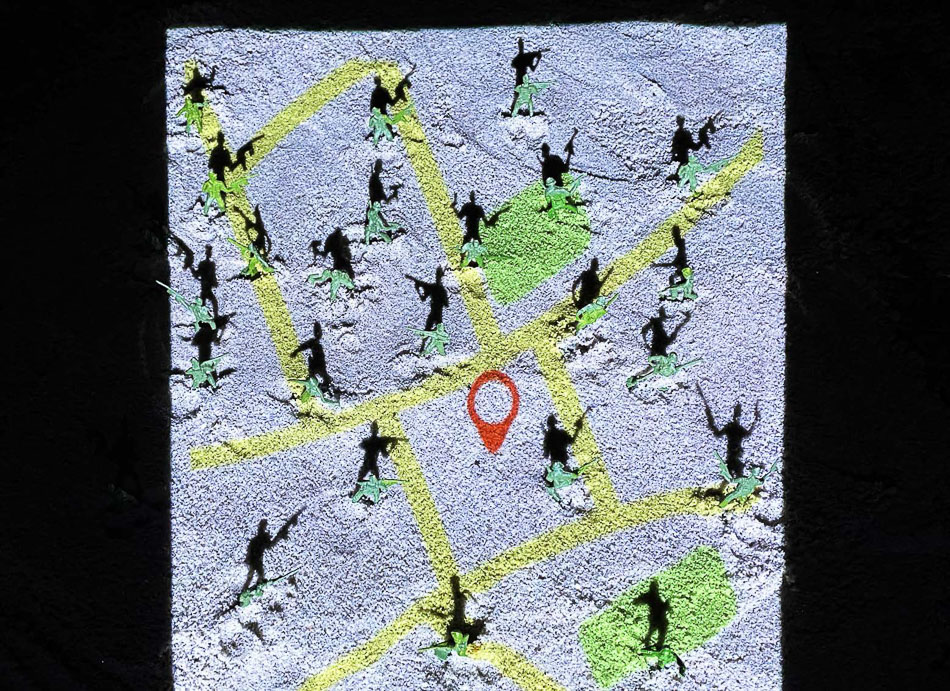

A reorganisation of the rural infrastructure sector is also underway. Over the last five years, companies like Syngenta, Bayer, and BASF have developed agricultural software and digital platforms which are installed on mobile phones to provide producers with agricultural recommendations. Today there are tractors equipped with artificial intelligence (AI) that collect information on soil humidity, composition, and the best location and the best season of the year to plant, etc. Farmers can also input their own data through their mobile phones. The collection of this data itself is not the problem, since in another social system this data could be harnessed to assist farmers in their work. In a capitalist system, however, the data is controlled by corporations for the benefit of their own profit-making. These companies own only the software but not the hardware, which is owned by other giants like John Deere and Bosch, who are developing AI and robotisation. The result of this is visible in robotic tractors, sensors, drones, etc.

These patents and the information produced by agribusiness giants need to be stored on the digital infrastructure of Big Tech companies: Microsoft has its cloud, Azure. Apple developed an Apple Watch for precision agriculture and created the Resolution app for farmers. Amazon has a storage function on Amazon Web Services intended for rural areas. Facebook is creating a digital consultancy app for farmers. Google has an institutional version of its Google Earth created for the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation, and so on. The primary consumers of these services are big agricultural producers in the commodity export market; meanwhile, 500 million peasant families do not have the means to access this new technology package. What they do have are their mobile phones, on which they can receive agronomic advice via SMS or WhatsApp based on information freely uploaded by other farmers. A large number of these applications are available ‘freely’ to small farmers in exchange for participating in a massive data-capture process.

This is where the issue of the integration of fintechs, Big Tech, and the agricultural giants emerges. In Kenya, Arifu – a company that belongs to the European telephony giant Vodaphone – offers agricultural consultancy via SMS and WhatsApp. Arifu has a partnership with Syngenta and DigFarm, enabling Syngenta to grow awareness of its seeds while DigFarm offers microcredit to Kenyan farmers. The structure of digital platforms makes this integration possible: they charge small fees, sell inputs, and allow for the use of digital currencies.

But how can artificial intelligence and the algorithm ‘read’ small farmers’ lands with their diversity of native seeds, for example, to enable corporations to offer free advice? Alas, this type of technology is intended for large extensions of land and monocultures. The integration of small farmers will not happen by selling technology packages but through microcredit and the digital currencies that have accompanied these platforms made available by the fintechs.

For this to happen, it will be necessary to reduce state regulation of the economy and of agriculture. This dynamic was seen most recently in India, where one million farmers occupied New Delhi, India between January and February 25 2021 demanding the scrapping of three laws that would put an end to the state regulation of the agricultural goods market. According to the new laws, instead of the state paying a fair price for peasants’ products, the market would be opened and deregulated, allowing big retail and technology corporations to take the place of and eliminate small retailers. In practice, this would mean that these large corporations would organise production and consumption in this sector.