The persistence of social inequality is directly linked with hundreds of years of deep-rooted patriarchal culture and with policies that have largely failed to expose and solve it.

Poverty is a long-standing, complex, multidimensional problem that permeates several aspects of society, including economic, demographic, political, social, ideological, and cultural ones. Internationally, there is a wide debate on how to conceptualize poverty and its definition, as well as on how to measure and fight it. Different formulations regarding what is conceived as “cost of living,” “indigence,” “unmet basic needs,” and “quality of life” are some of the variables taken into consideration when analyzing and defining it.

Under the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), poverty is comprehended as the deprivation of necessary conditions within a specific society so that its members can generate resources, fully develop, enjoy human opportunities, and achieve social goals. The term “human poverty” is presented as the antithesis of human development, as it is the denial of options and opportunities that can guarantee a long, healthy life with access to knowledge and social participation.

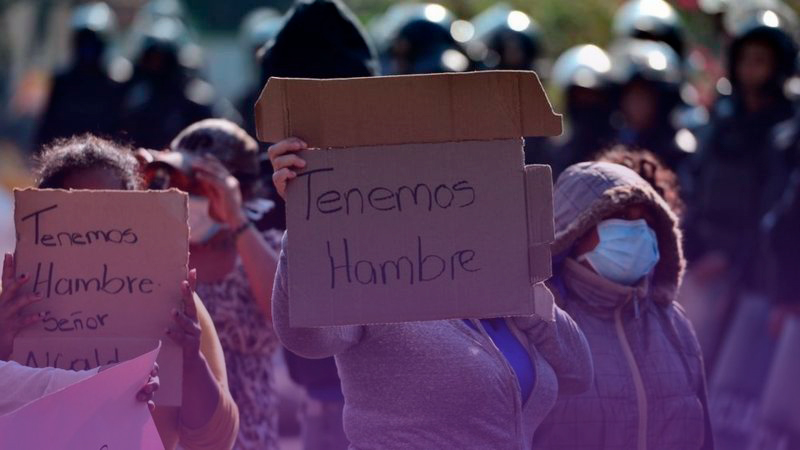

Poverty manifests itself in gender gaps or gender inequality across different aspects of society, particularly in terms of opportunities and access to health, education, employment and social security, and wages or income. Several organizations and institutions across different levels address the matter of women’s poverty as an expression of gender inequality. It’s through this approach that a gender perspective emerges and, therefore, the analysis of what is known as the feminization of poverty, influenced by factors such as violence.

Feminization of poverty and structural violence particularly affect women in Latin America and the Caribbean. Both phenomena are associated with historical factors. One example is the fact that Black people, Indigenous people, and women in poverty are often faced with more barriers preventing them from accessing justice and human rights. Many of these obstacles are the result of gender inequalities and the way they are replicated in institutional and government policies.

Structural gender violence has been named as such due to the need to explain interactions of violent practice across different social spheres. It’s not only about political repression, but also about alienation and the lack of access to goods and opportunities.

The persistence of social inequality is directly linked with hundreds of years of deep-rooted patriarchal culture and with policies that have largely failed to expose and solve it.

One Step Toward Exposing Reality

Since the 1980s, the phenomenon of poverty has been more thoroughly analyzed from a gender perspective. A study by the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) published in 2004 showed that “poor women outnumbered poor men, that women suffered more severe poverty than men and that female poverty displayed a more marked tendency to increase, largely because of the rise in the number of female-headed households.”[1]

Talking about the feminization of poverty is a way to demonstrate that men and women experience different realities regarding the economy and social life. Gender is a marker of poverty as much as race and ethnicity, geographic location, and even age.

As the Indian feminist researcher Gita Sen points out, “the probability of being poor is not randomly distributed across the population.”[2] The sexual division of labor imposes the domestic space and under-appreciated labor on women, thus establishing “inequality in the opportunities they have, due to their gender, in accessing material and social resources (productive capital ownership, paid labor, education, and training), as well as in taking part in major political, economic, and social decision making,” as researcher Rosa Bravo points out.[3]

She also points out that not only women’s material goods are scarcer, their social goods (education, culture, things that are accessed through social and cultural bonds) are also insufficient, due to their work conditions, as spaces are limited by the sexual division of labor, with hierarchies and separations. Women experience deprivation in the labor market, in the social protection system, and in their households. Today, we see how this reality has become aggravated in the region due to social isolation in times of pandemic.

According to the ECLAC document mentioned above, illiteracy rates are another manifestation of the constraints women experience in the labor realm. In 1970, in Latin America and the Caribbean, 30.3 percent of women were illiterate, over 22.3 percent of men, among the population aged over 15. While the gap has been reduced, it still remains: in 2000, the rate of illiterate women was 12.1 percent, while 10.1 percent of men were illiterate. One of the reasons why women leave school in adolescence is precisely because they have to undertake domestic labor.

The document also points out a significant increase in women’s economic participation as of the 1990s (from 37.9 percent in the early 1990s to 42 percent in 1999), but over the course of the years, the unemployment gap between men and women has gone up, not down.

From Reality to the Premises of Struggle

The feminization of poverty must not be looked at only in terms of precariousness of female-headed households. This means it must not be considered an isolated thing, as if it were a fact with no implications for families, communities, countries, and regions.

Indeed, global migration has been one of the main causes behind the feminization of poverty. Today, nearly half of the world’s migrant population are women. Several factors influence women migrating, including globalization, the desire for new opportunities, poverty, vulnerability of certain cultural practices, gender-based violence in their home countries, natural disasters, war, and internal armed conflicts. These factors also include the aggravation of the sexual division of labor in different industrial sectors and service industries in their destination countries, as well as a male-centric entertainment culture that creates demand for women as providers of this kind of entertainment.

How much has COVID-19 pandemic lock-down restrictions contributed to this reality? How have governments across the continent been treating this phenomenon? What’s the impact of public policies in changing this reality? What has been the contribution by feminist movements’ struggles across the region? These are questions that remain from this initial analysis into the matter.

[1] Understanding poverty from a gender perspective, published in English and Spanish by the Women and Development Unit of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), page 12.

[2] “El empoderamiento como un enfoque a la pobreza” [Empowerment as an approach toward poverty], published in Spanish in the book Género e pobreza: nuevas dimensiones (1998), by Ediciones de las Mujeres (Chile).

[3] “Pobreza por razones de género. Precisando conceptos” [Gender-based poverty. Clarifying concepts], published in Spanish in the book Género e pobreza: nuevas dimensiones (1998), by editora Ediciones de las Mujeres (Chile).

___

Marilys Zayas is a member of the Cuban Women’s Federation and the World March of Women.