When we talk of authoritarian governments, we do this based on what happens in other countries, because we see that authoritarianism advances and deepens to the same extent as neoliberalism does. Amid this pandemic, the meaning of this regime becomes more and more evident, as well as the need to change and build something different.

In Latin America, we may say that Guatemala, Brazil, Panama, Paraguay, Colombia, and other countries are very similar in their authoritarian governments scheme. They want to accumulate more capital by using military power, by stealing natural resources and, above all, by intensifying political, economic, cultural, and social violence. In most of such countries, there is no sovereignty, and the neoliberal model has been for a long time imposing conditions that make us dependent on imperialism.

The Background for the Conflicts in Colombia

Now I will concentrate on what is happening in Colombia, but, as I said, it is very similar to what happens in other countries. Although it has been five years since a peace deal was signed with Latin America’s biggest and oldest guerrilla group, unfortunately we’re still living amid an armed conflict.

Defending land, the territory, and peace is high-risk work. From the signature of the deal to August 14th, 2021, more than 1,224 people were killed, mostly people from rural areas, peasants, Indigenous people, and Black communities. There has being a sharp increase in mass killings and mass displacements in the country: 53.8% more than in the first half of 2020. This year, more than 378 people have been killed in mass killings. People are being killed because they have taken part in the national strike, which was an upsurge of social unrest. A young woman leader of the mobilization and other two women were killed on August 23rd.

Although it is said that most people killed during wars are men, femicide rates in Colombia are very high, especially considering that we, women, are war booty, objects of rape. Girls are victims of sexual abuse from a very young age, and many of those girls who go to the demonstrations and are taken by the police are raped in prison.

The creation of “false positives” is part of the war in Colombia. That means that the Colombian Army, by order of the president and of the generals, cunningly recruits young poor people, offers them a job and them kills them, puts the uniform on them, says they are guerrilla members and that they died in action. Thanks to the women’s organization for justice, they were able to prove this was happening, and generals have been convicted due to such “false positives.” In Colombia, organization and women empowerment is the only way to survive amid the war.

In the most remote districts (veredas), in rural areas, we, as women, play an important role in the organization of community as a whole. Nevertheless, I must say that our districts are militarized. Many murders are hidden, and people are afraid to denounce them. From the National Federation of Agricultural Trade Unions [Federación Nacional SindicalUnitariaAgropecuaria—Fensuagro], we have reports of a very large number of killings and disappearances, but we don’t denounce them, because families say that, if they do, they may be the next targets.

Colombia is fully militarized. The military power plays a key role in Latin America as a whole, but Colombia is especially strategic for the United States to intervene in Venezuela and other countries.

Peasant Women Struggling for Recognition

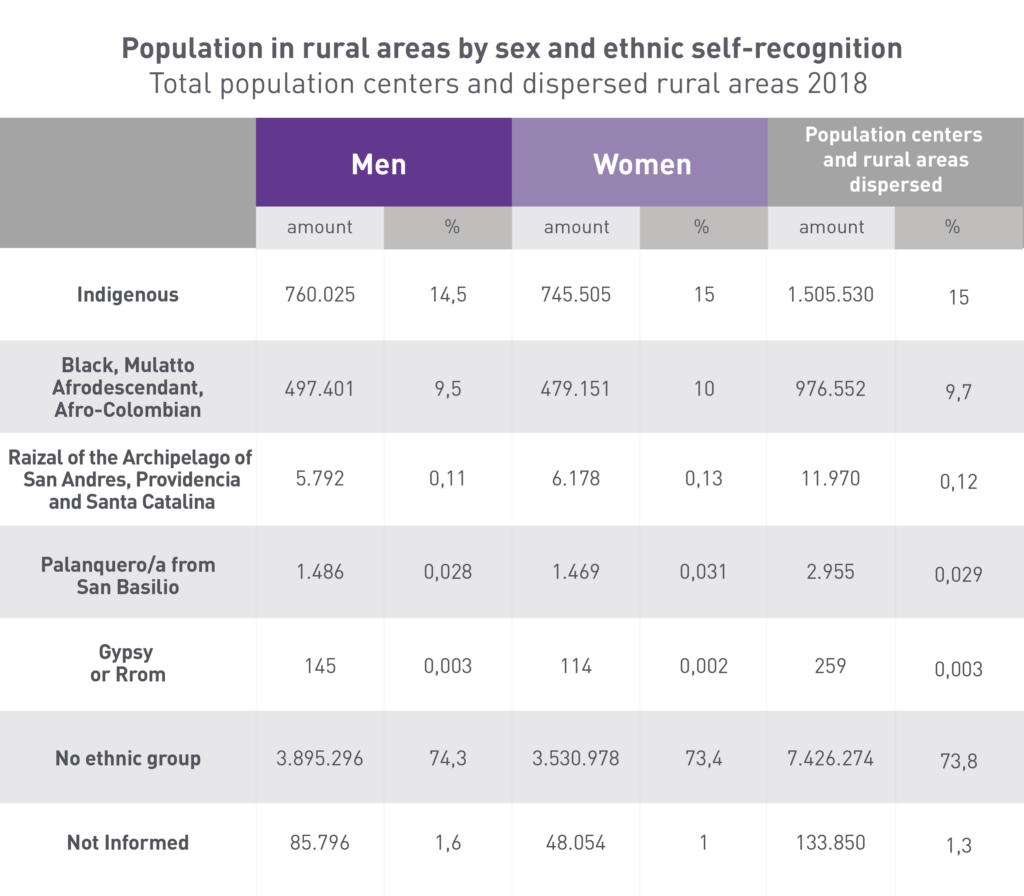

The institutional recognition of the Declaration on the Rights of Peasants is highly important to us. The table below helps us visualize the relevance of the struggle in Colombia, in Latin America, and around the world for recognition of peasant people as subjects of rights.

The “no ethnic group” fields in the table refer to peasants. We are 73.8% of the rural population of the country and, despite that, they don’t recognize us as peasants.

According to the Political Culture Research (Encuesta de Cultura Política—ECP), 83.6% of women interviewed in the scattered rural centers and districts identify as peasants. However, Colombia doesn’t recognize our Declaration. The rural population’s activities are being taken into consideration, but with no distinctions, since we are not recognized as subjects of rights.

In Colombia, women live in poverty, particularly peasant, Indigenous, and Black women. Age doesn’t matter: even when they are elderly, they have to keep working hard in quite precarious sanitary conditions, now worsened by the pandemic.

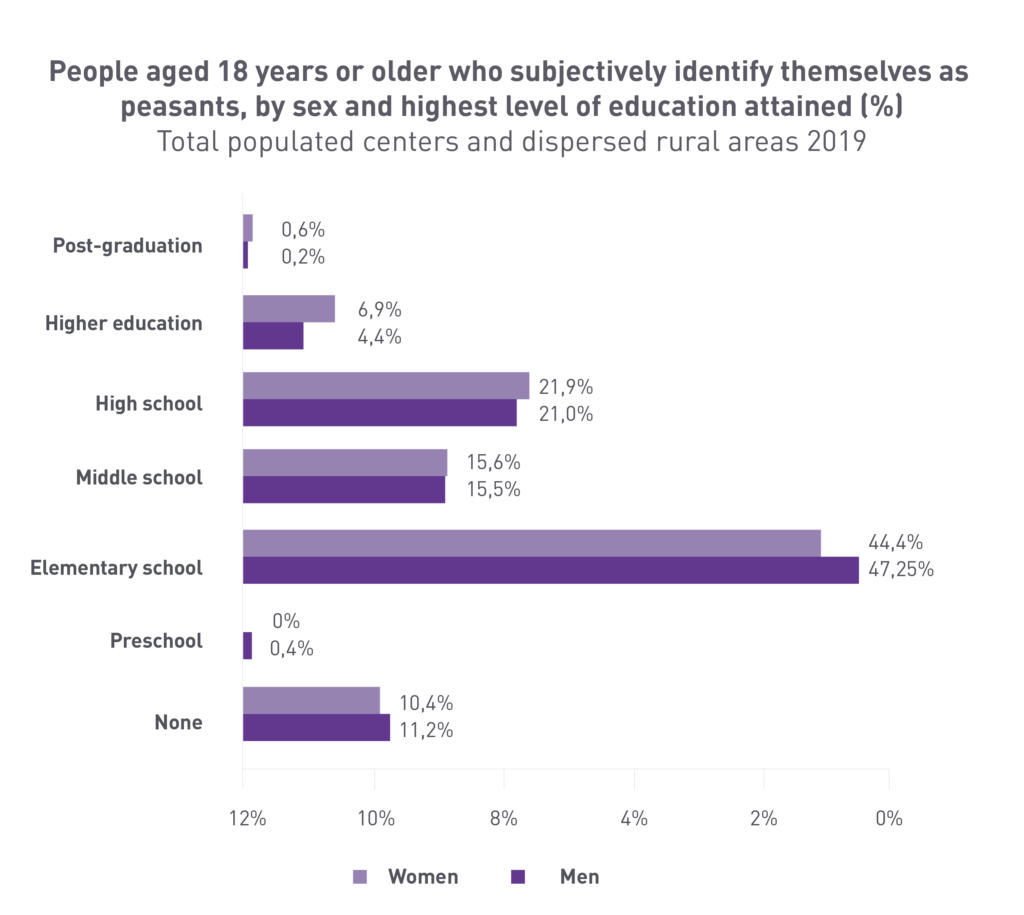

This same system forced women into being responsible for their families while they work outside the home. The research shows that there are no study opportunities. The possibility of getting into higher education is minimal. The majority of the population is limited to elementary school: to learn how to read and write. Work, in turn, is hard, because agribusiness has established large monocultures (such as banana and sugar cane), where women work as hard as man and earn lower salaries and have access to lesser conditions.

Despite all of this, we keep working and organizing resistances to keep advancing and buildingfood sovereignty. More than 15 million tons of food are imported every year. Despite the violence, the neoliberal attacks, and the oppressing laws enacted by the Congress, we keep organizing and farming with the social responsibility of peasant life and women.

Why We Need to Organize

In view of such negative, inflexible, and harsh circumstances, we argue that the organization must be the basis to support us in getting out of the crisis and building a new country. The only way to learn about what is happening and understand the meaning of this economic model that has an urge for destroying nature and humanity is through education. Not that from the traditional school, but rather grassroots education from the organization.

When we talk of organization, we talk not only of the small portion of the district, of the states, or of the country, but of an international alliance that enables unity and a model vision. When we say that we are women peasants, we say that the struggle must involve both rural and urban areas. One social sector alone cannot solve all issues. Unity among the people around the world is of essence.

The events in Turkey, Afghanistan, and in so many parts of the world must move us. We have to mobilize on a global level to have people’s rights be respected and the authoritarian governments, which advance day by day, be overthrown.

Popular Peasant Feminism

Popular peasant feminism is an integral part of the historical construction of what we live as women, and it is in our practices and our daily lives. The World March of Women has been helping us to build what feminism means: it must be collective, organic, and have its own and common identity that encompasses our work.

This globalized world wants to put an end to the peasant way of living. But we have a social duty to food sovereignty and food production. Our struggle for land is part of the feminist struggle. This is how we are, how we live, and how we farm the land. Our proposal is to politicize food sovereignty, politicize our own practices and, above all, discuss everyday life and social relations. If we fail to do so, we will separate ourselves from our sisters and comrades.

Our campaign to face violence against women is also a responsibility of the men of our organization. Change is not implemented through decree. We may create numerous laws, but they do not necessarily translate into action—as it happens in so many countries, where, although there are laws regarding violence against women, femicide doesn’t stop. The change we must make is one of consciousness, created day by day through discussions with our sisters and comrades, with society, and with other organizations. We need to start now. We can’t wait until we manage to change the government or to carry out the revolution to have new men and women.

____

Nury Martínez is a member of the Latin American Coordination of Rural Organizations (CLOC-Via Campesina) and of the National Federation of Agricultural Trade Unions [Federación Nacional SindicalUnitariaAgropecuaria—Fensuagro] in Colombia. This article is an edition version of her contribution to the “Feminist Struggles to Bring Down Authoritarianism” webinar, organized by Capire and the World March of Women on August 24th, 2021.