It is no overstatement to start this writing by saying that much of what grassroots feminism is today—in Brazil, Latin America, the Caribbean, and internationally—has the hands, the heart, the mind, and the militant energy of Nalu Faria (1958-2023). Nalu dedicated her life to building democratic, necessarily feminist and internationalist socialism. Beyond speeches and great narratives, she liked to be there in actual strategic building processes, sitting in circles, building syntheses, consensus, organization, and struggle.

We can write about Nalu from macro to micro, from local to international, or vice versa. Her practice was the expression of these and many other connections. In her farewell ceremony, Nalu’s contribution beyond the World March of Women was clear. Her sisters in struggle said she had many “homes.” One of Nalu’s homes is the SOF Sempreviva Feminist Organization, of which she was a member since the 1980s, where she was a coordinator, an organization that is a point of reference in grassroots feminist education, in feminist economy formulations, and in building the World March of Women in Brazil. Even before the WMW emerged, we see Nalu’s commitment, through the SOF, to bulding working class feminism—a milestone in this history was the feminist education efforts of the Cajamar Institute.

When the call to build the World March of Women came to Brazil, the SOF and the women’s secreatriat of the Unified Workers’ Central (CUT-Brazil) were the country’s representatives in this process. With her SOF sisters, Nalu saw in this proposal the possibility of building an international feminist movement with an anti-capitalist agenda to challenge the dynamics that had been institutionalized and guided by the UN agenda. From then on, she and her sisters became invested in this movement building, step by step, in Brazil and internationally, to make this possibility a reality.

Nalu had an eagle’s eye—she could see very far. Her strategic thinking was always coupled with her attention to detail: about the processes, the words used in writings and slogans, the colors on stickers, and the deeply political aesthetic expression of our feminism. Nalu said that the struggle has to be beautiful and colorful; it requires aesthetics that reflect the joy of women workers. Even when the topic was violence against women, there should be emphasis on the ability to overcome it, on resistance, on women’s strategies to break free from violence, overcome the pain, and defeat patriarchy.

In Brazil, the constitution of the WMW as a grassroots, diverse, left-wing movement carries the accumulated processes Nalu has been involved in since the 1980s. Since she first started her activist work—in the student movement in Uberaba, Minas Gerais, then moving to São Paulo—, another of Nalu’s “homes” was the Socialist Democracy, a faction of the Workers’ Party (PT). Nalu also greatly contributed to women’s self-organizing efforts in the PT and CUT. The struggles for child care and quotas for women’s participation in political spaces—including boards of directors—emerged from political formulations about the sexual division of labor as the basis of women’s oppression. These struggles have marked this process, where Nalu also worked to affirm that women workers are the political subject of feminism.

Nalu argued that the history of feminism was something we all needed to know well, identifying ideological continuities that sometimes seemed to be resolved, but would re-emerge in complex ways, traps that depoliticize the movement and weaken the collective subject. She encouraged us to learn about the history of socialist feminists, their internationalist movement building efforts, and their debates with the socialist movement and bourgeois feminism; the history of women who struggled for independence and against slavery in their countries; the history of women’s organizations, of different feminist currents and theories, but also the history of women’s groups in their neighborhoods.

Nalu always made a point about not creating hierarchies between those who think and those who do, and between generations, to understand the demands of each time and place by building syntheses that can take our struggles forward, without losing sight of our horizon of change when defining strategies and political efforts.

“How will this demand change the model and not just settle women a little bit more on the structure of capital?” she would ask. Nalu was one of the leaders of the victorious campaign against the FTAA in the Americas. And she insisted, in every step of this struggle, that it was not enough to “include” women in that neocolonial agreement, because the entire agreement had to be defeated, and the only way to do it was through great grassroots mobilization. From that struggle, feminist economy eventually consolidated in the formulations by Nalu, the WMW, and the Latin American Network Women Transforming the Economy (REMTE). It was not enough to identify that project’s negative impacts on women and work to alleviate them, because it was a neoliberal project by imperialism, which had patriarchy well articulated into its core.

Structural adjustment and reduced state ability to ensure rights and public services is only possible by increasing the amount of unpaid work women carry out to sustain life in the most precarious conditions. Bringing the sustainability of life to the center of politics and the economy and changing its structure, giving new balance to the production and reproduction spheres, are part of the feminist economy Nalu conceived and practiced throughout her political history. She said that, during difficult times, we must radicalize even further; we cannot give in to what seems to be the limits of the situation—we have to work to expand the frontiers of what is possible.

Nalu has always respected the political processes and preserved spaces of dialogue, addressing divergences, but building consensus, which is fundamental to build unity and make grassroots organizing massive. Nalu’s energies were complemetarily dedicated to women’s self-organizing and building strategic alliances with mixed-gender social movements. She was a great partner of women from the movements to discuss and build their own feminist perspectives, strengthening the movements as a whole. There are so many stories about Nalu’s importance for grassroots feminism from movements and organizations including La Via Campesina, the Landless Workers’ Movements (MST), Friends of the Earth, the Grassroots Movements’ Central (CMP), the National Students’ Union (UNE)—the list goes on. Ever since the first edition of the Margaridas’ March joining the WMW in 2000, Nalu has actively contributed to building it, which is Brazil’s largest mobilization of women workers from rural areas, water-based, and forest communities.

Nalu was a point of reference for the Brazilian and Latin American left. She worked on the People’s Brazil Front, the Continental Day for Democracy and Against Neoliberalism, ALBA Movements, and the International Peoples’ Assembly. In these and other spaces, she discussed the political and economic situation, proposals for Brazil, for regional integration and peoples’ sovereignty, for the anti-imperialist struggle, always coming from feminism. And this is one of Nalu’s great legacies for the left: it is necessary to overcome the view that feminism is separated from the socialist struggle, as if it were something “specific,” only subordinated to the “general” struggle.

The revolution Nalu fought for is necessarily socialist, feminist, anti-imperialist, and anti-racist. The ability to organize this struggle is built on the ground and by facing contradictions that are felt and experienced by the peoples, without fragmenting the struggles, but forging syntheses and finding in the grassroots struggle the solutions and alternatives that must guide anti-systemic political proposals. In this sense, Nalu contributed and was close to the CF8 Feminist Center March 8 in Rio Grande do Norte state, an organization that is also a member of the WMW coordinating body in Brazil. She draw attention to the way how organizing and actual economic transformation processes changed different dimensions of the lives of women from the state.

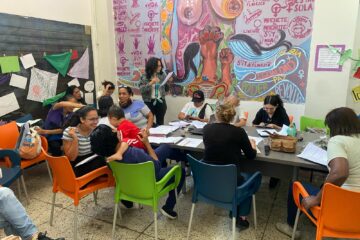

From Nalu, we learned the practice of feminist grassroots education. Across Brazil, we find activists from different generations who remember the workshops she facilitated, and which changed their perceptions about different topics. We learned that there are different ways to express how we see and experience difficult topics—from personal-political to geopolitical. We learned that political education is a process in which we face contradictions, untie knots, and move forward as a group, strengthening political subjects. “What was it like to do this activity? How did you feel?” were questions Nalu never forgot to ask after group dynamics. The answers would take a step further to disrupt the patriarchal dichotomy between reason and emotion. Nalu also left workshops with new perceptions. Her presence in the Emancipatory Paradigms meetings in Cuba, for example, brought inspiration and strength from people power building practices to our Brazilian experience. “What we learn, what we share, and pass along,” Nalu wrote about methodology. In recent years, Nalu has brought that accumulated reflection to the Berta Cáceres International School, always committed to listening and engaging in dialogue, even with the challenge of doing so on a virtual space, with different languages, and always having little time.

Since 2016, Nalu integrated the International Committee of the WMW, leveraging the WMW organization in the Americas and contributing to building the movement’s political agendas: from the formulation of the criticism against transnational corporations to the notion of the capital-life conflict and the processes of alliances and building of Capire.

All of these “homes” Nalu had were part of her community. And community is built from personal and political relationships, through care, affection, and solidarity. And also through joy, music, food, and party. All of these things mark Nalu’s story, recorded in different accounts by women and men from different generations and countries. Nalu sowed feminism, internationalism, and connection between struggles. She sowed many seeds, watered them, nurtured them, always willing to discuss, listen, and think together.

Nalu was one of those extraordinary people that we can tell they are when they cross our paths—with a unique characteristic that Nalu not only crossed our paths, but would stay with us, building pathways together.

Her passing due to a heart disease on October 6th this year left us with great sadness and sorrow, but with a great commitment to keeping her memory alive and finding ways to continue Nalu’s march, together.

Heritage

Poem by Camila Paula

The indignation and ability to organize the struggle

With commitment, strength, and tenderness

Of a revolutionary feminist

Has written so far the history that finds us today

Not ready, but standing to continue to write

The urgent radicality of a new time.

Well! To look at the horizon of a different world is a collective exercise

– yesterday and now –

And if a lighthouse turns off on the outside,

It’s time to enkindle what’s inside:

Deep from our backyard-continents

Let us be beacons of the stubborn hope we have learned

Joining hands: tenters of red-purple flags

Until the peace flag flutters

On this Earth in all its corners!

The pathway, comrades, remains the same:

The common good of equals.

Let us not be apart.

Let us do as we know –

With passion and yielding to no tyranny!

Sisters, friends, the March of rebellious solidarity still burns in us.

To dream, love, and change the world

Like Nalu Faria would.

Until we are all free!

Tica Moreno and Maria Fernanda Marcelino are World March of Women militants from Brazil.