We, as feminists, have the task to turn data into information, then turn information into knowledge, making it possible to measure and appreciate unpaid work and change the organization of this kind of labor.

Turning data into information, information into knowledge, and knowledge into decision making. These are the three steps of the statistical reflections on the work carried out by Cuban women toward an agenda grounded in feminist economy.

Feminist economy centers its concerns around the sustainability of life and the fulfillment of human and non-human needs. It integrates the production of commodities and the social reproduction of people into one process. All activities carried out to maintain a home are considered work and are appreciated as an economic contribution to society.

Sustaining Life

The fulfillment of human needs is the result of the process of production of commodities and reproduction of people. A powerful analysis of feminist economy allows to put the purpose of non-commercial work inside the household into play. Care work is essential for the sustainability of life and for the reproduction of labor power and society, and it generates a fundamental contribution for economic production, development, and welfare.

This is fundamental to review and expand the concept of work itself. Caring for other people is work. Economics and feminism are brought together to develop concepts, milestones for analysis, and research to provide a better understanding for the economy, as well as more evidence, tools, and knowledge for feminism.

Why Is Caring for Others Work?

Resolution I of the 19th International Conference of Labor Statisticians, which took place in 2013, broadened the definition of work: “work comprises any activity performed by persons of any sex and age to produce goods or to provide services for use by others or for own use.” The so-called “third-person principle” establishes this difference: if someone else can carry out an activity for me, it’s work. If it is non-transferable, then it is not work.

This is why work, as a concept, is different from employment. Work can be paid or unpaid, formal or informal, it can be carried out in or outside the home, it can take place in different pleasant or unpleasant circumstances and provide a wide range of rights and opportunities, which may reflect different contexts and stages of development. Employment provides income, economic participation, and financial security. Therefore, limiting the analysis to employment would be restrictive, as it would not include several types of work that are much more flexible and may be carried out for an undetermined period of time, such as care work provided for family members and volunteer work.

Activities carried out in and for the household correspond to labor time and contribute for the development of productive forces in society. The topic of time is key: how can time limit the development of human capacities? The answers are found in how necessary it is to produce in order to reproduce life, and how the “private” space of the house is subjected to the “public” space, the space of work and patriarchy.

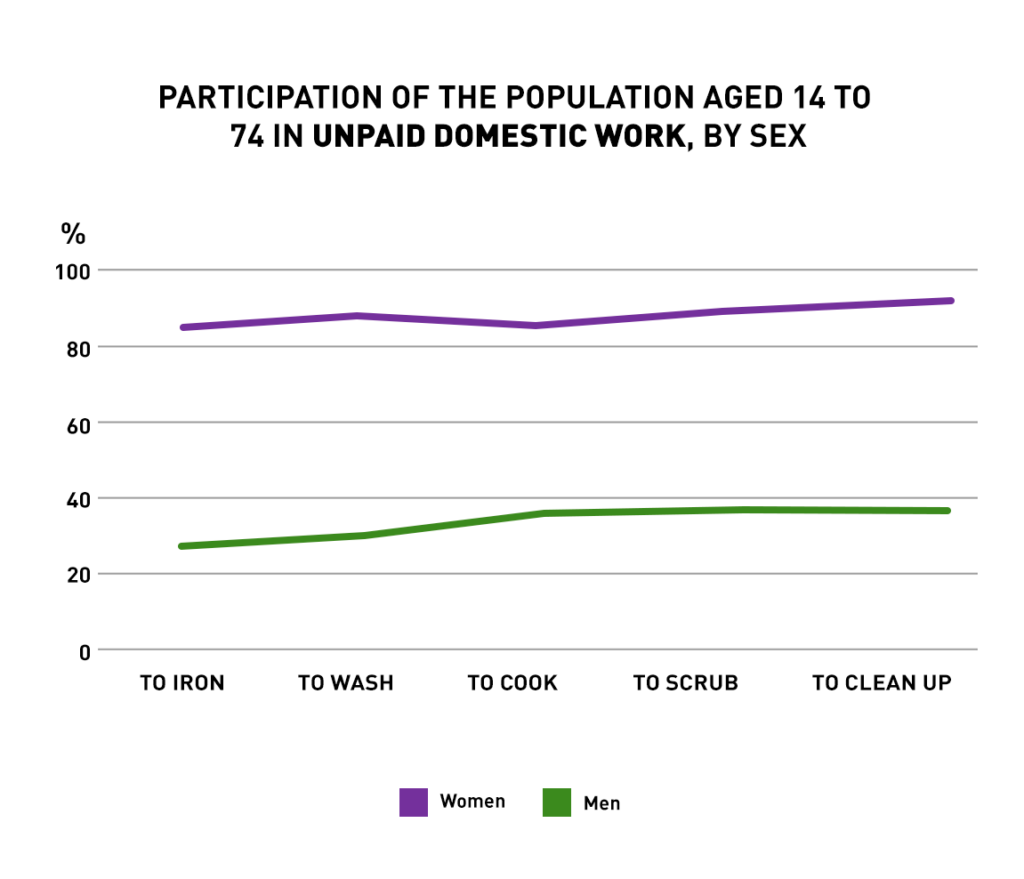

The organization of families takes place as domestic work becomes normalized and internalized. The sexual division of labor comprehends the distribution of productive and reproductive labor between the household, the market, and the state, as well as between men and women, which implies women’s economic subordination. This poses the questions: who does what, who has what, who decides what?

The answers allow us to see the gender inequalities that exist in our society. They are built into the spaces of socialization where patriarchal cultural standards prevail. In this sense, female subordination and male power are subjectively and uncritically incorporated into behaviors as if they were natural.

Gender inequality can be represented by quantifying gaps in access, use, or control of resources and services for development, such as healthcare, education, land, credit, housing, technical assistance, and information. Acknowledging these inequalities makes it possible to identify what is necessary to achieve equality between women and men in terms of opportunities, participation, and ability.

Cuba: Stop Associating Care With “Natural” Abilities and Externalize Domestic Work

In Cuba and so many other places around the world, we face a challenge to promote practices that can increase women’s paid employment rates throughout their life cycle, in any context, and under equal conditions. This must be a continuing challenge in the process of economic and social change taking place in Cuba for 60 years.

The vision of the nation we want to achieve comprehends equality and human rights as conditions for citizenship. New opportunities coming from reforms to modernize the economy make it clear that people come from different backgrounds according to their gender, sexual orientation and identity, geography, resources, race, and age. Because of that, not everyone is able to enjoy the same opportunities, the same way.

But, when it comes to Cuban women’s reality today, we are the majority in activities and jobs providing services that are less productive, whether in state-run sectors or not. Most activities that can be performed as self-employment are still traditionally done by women, with little value added. According to the 2012 Population and Housing Census (CPV in the Spanish acronym), 36.4 percent of women over the age of 15 responded that their primary activity is house work, self-identifying as “homemakers” because they are dedicated to unpaid domestic and care work and don’t earn an income of their own. These numbers are similar across the Latin American region, although with differences in the levels of education and production that Cuban women have.

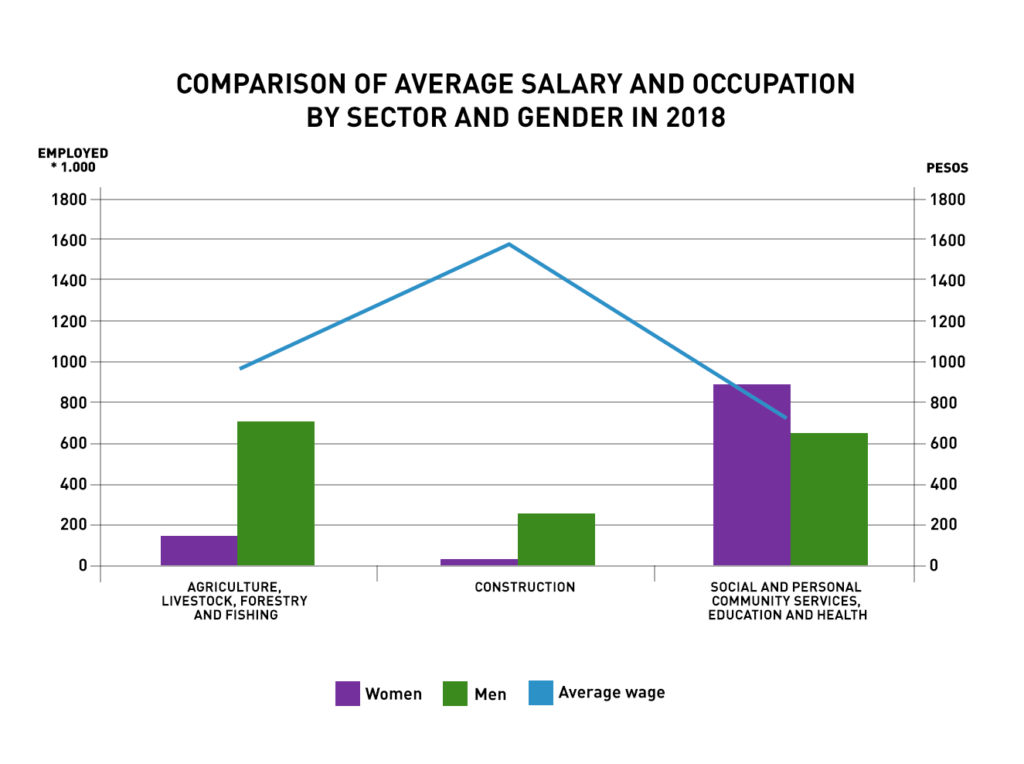

Women working on their own account are represented in sectors such as food preparation and selling, home rental, telecommunication services, child and elder care work, beauty and personal care services, repair services, manufacture and sales of garments and arts and crafts. As these types of work are underappreciated, this becomes a waste of the high levels of education of Cuban women and discourages them. Around one third of informal workers are women. Most women who work on their own account are hired by someone, while men mostly own their own business.

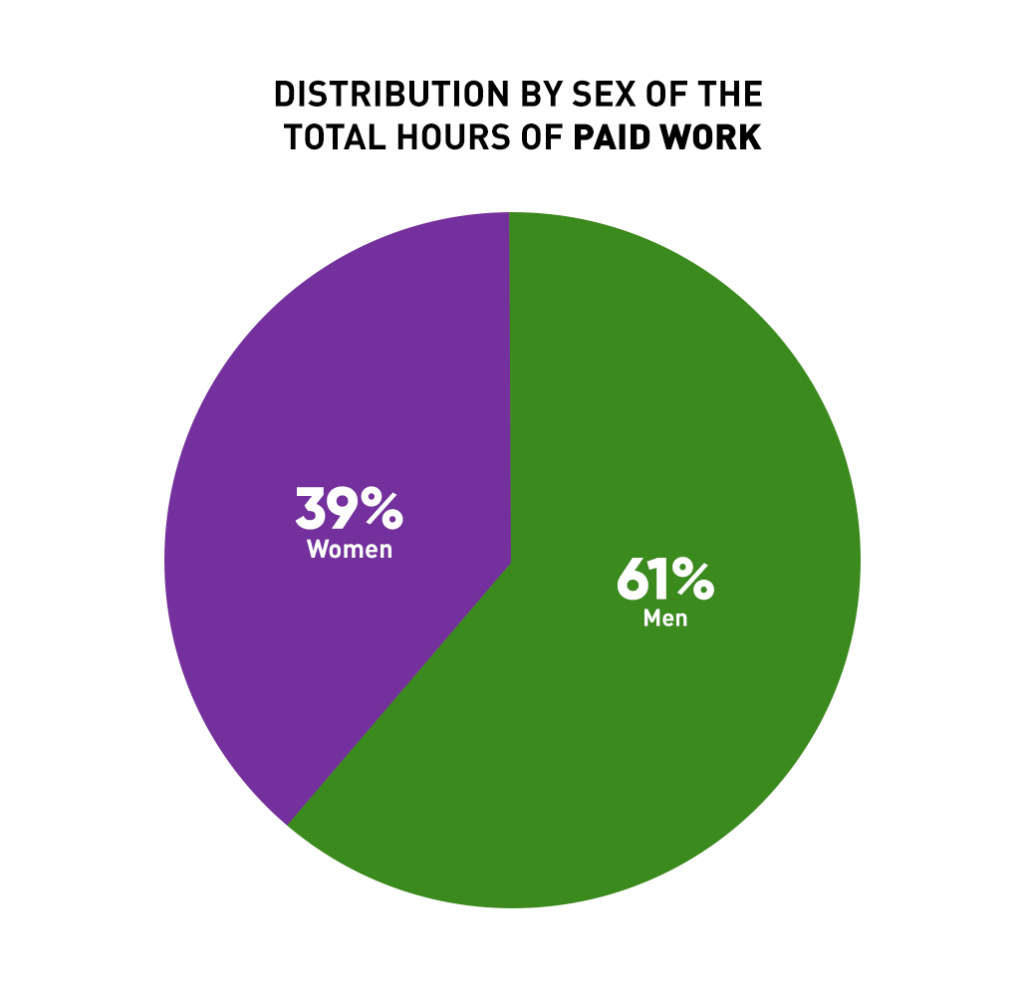

The law requires equal pay for equal work for women and men in the public sector. However, women are the majority in the service sectors in which average wages are lower than in the construction sector, where most workers are men. Additionally, the exodus of women from jobs in the public sector is not being followed by an increase in their participation in other industries.

Pinpointing Inequalities and Quantifying Disparities

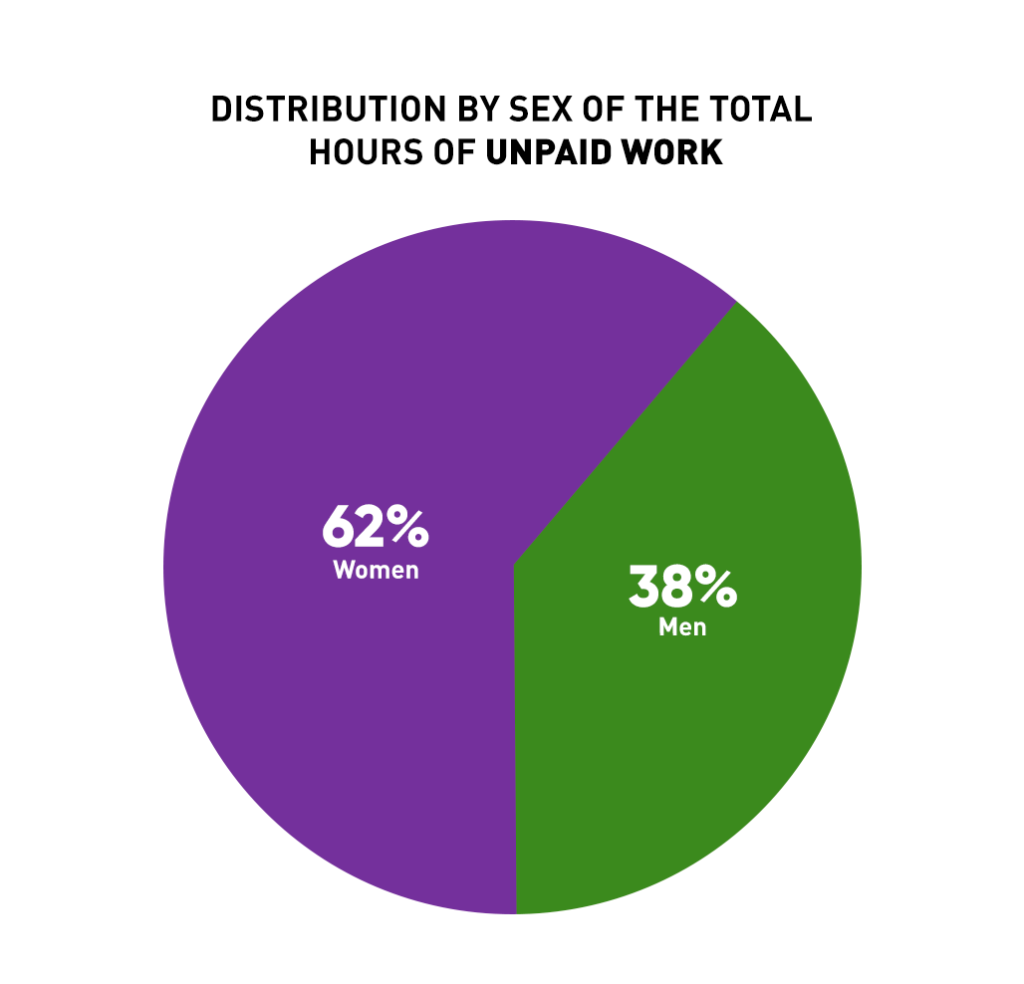

An empirical approximation of two different surveys on the use of time, conducted in 2001 and 2016, despite using different methodologies, showed that the number of hours women dedicated to paid work in 2001 represented 50 percent of the number of hours dedicated by men to paid work. Meanwhile, the 2016 survey showed that the number of hours dedicated by women to paid work was 64.5 percent of the hours dedicated by men. However, when it came to unpaid labor, in 2001 and 2016, women worked 64 percent more hours than men. These results show there is a trend toward equating the number of hours dedicated to paid work by men and women, while the gap in the allocation of time to unpaid work remains. The data measured from different moments in time, regions, and municipalities show an unequal allocation of time and domestic chores between women and men.

We, as feminists, have the task to turn data into information, then turn information into knowledge, making it possible to measure and appreciate unpaid work and change the organization of this kind of labor.

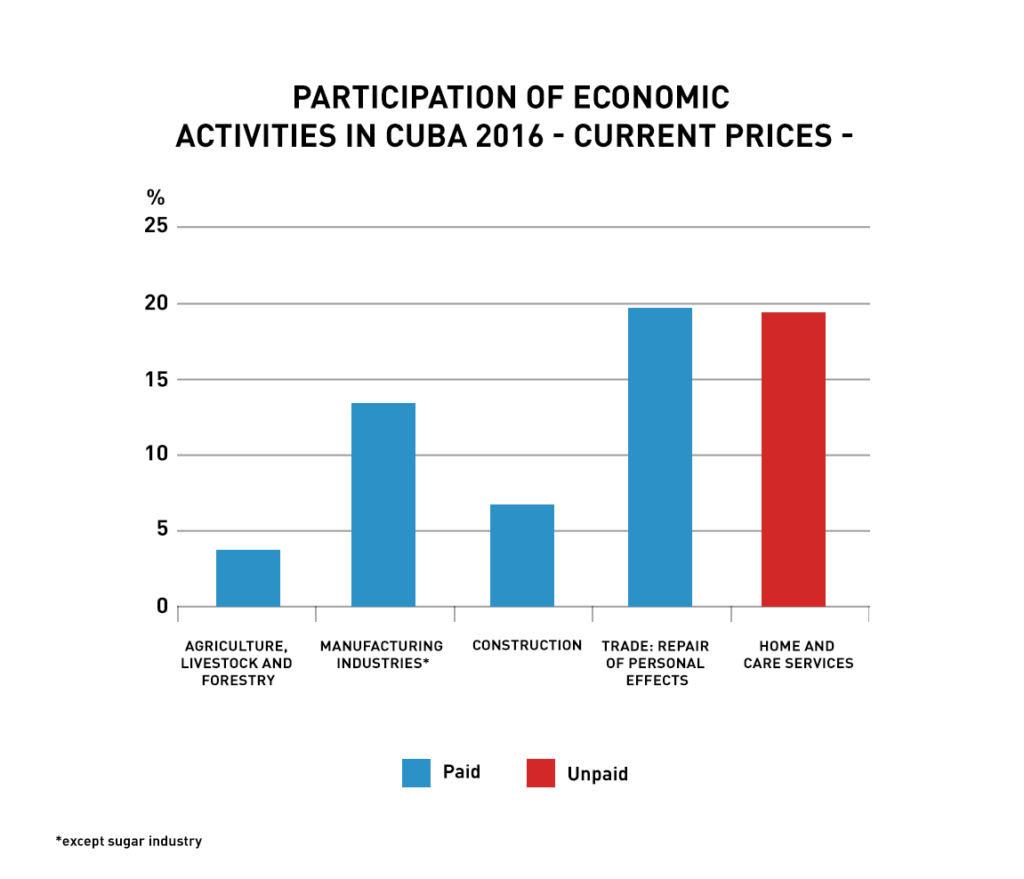

The monetary value¹ of unpaid domestic and care services represents an estimated 19.5 percent of the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP), in current values. This is a significant share, as it is larger than the added value of the manufacturing industry, and it is only smaller than the share of the commerce and renovation industries. Meanwhile, the updated monetary value of domestic and care services went up 36 percent over 2002. Women contribute with 85 percent of this monetary value. These figures show the contribution that, from within households, secure the sustainability of life.

An Agenda by Women

This year, the National Program for the Advancement of Women [Programa Nacional para el Adelanto de las Mujeres] was signed, an agenda pushed by the Cuban state that will likely mean a moment of continuity, advancement, and development toward gender equality in the country. The program includes propositions such as fully and effectively achieving the prevention and elimination of expressions of discrimination and violence against women and promoting equal rights, opportunities, and possibilities as secured in the country’s Constitution. This means dedicating more attention and building policies for economic empowerment, education, prevention, social services, sexual and reproductive health, access to spaces of power, and other topics.

The guidelines designed in the proposal are related to pushing education and training actions from childhood, aiming to foster inter-personal relationships based on equality, respect, and shared responsibility, and including gender issues in education plans and programs for all types and levels of education.

From the public sector, we must draw the experience of the organizing methodology for care systems, and modernize it. There is a state infrastructure that should be used as a tool to establish different forms of organization for the management of care services, based on the reality of each different territory.

Support services cannot be all conceived the same for different provinces, municipalities, rural areas, mountain ranges, or coastal areas. Across the island, we have the task of promoting spaces for action and conversation about the role of women in the public and private realm with families, communities, media outlets, civil society, and student and union organizations. This will foster feminist economy in Cuban women’s lives and work.

¹The concept of “monetary value” is part of a methodological approach that aims to estimate, though with limitations, the economic contribution of unpaid domestic and care work. The calculation is based on market values adopted by each society to assess the value of unpaid work, mostly carried out by women, to maintain and sustain life.

Teresa Lara Junco is a feminist economist and researcher. She is a member of the National Network of Care Studies in Cuba. This article is based on Teresa’s constribution to the Berta Cáceres International Feminist Organizing School during the Feminist Economy workshop carried out on June 8th, 2021.