The Venezuelan feminist anthropologist Iraida Vargas once said in an interview: “The first thing capitalism takes from us is our story, our memory.” In doing so, capitalism also expropriates part of our soul—I always add that every time I quote her.

The expropriation of memory is a mechanism that operates and is part of symbolic and cultural oppression. It is at the base of a system of multiple oppressions: capitalist, colonialist, patriarchal, racist.

As our memory and our story are expropriated, our identity and our autonomy are attacked to create certain kinds of subjectivity and therefore create certain forms of organizing the world and life. The encroachment of memory deprives us of our own references, ones that incarnate our values, struggles, and principles.

The alleged lack of our own history and memory prevents us from seeing ourselves as peoples who create our own destiny. It legitimatizes racism, colonialism, capitalism, sexism. It legitimizes our own oppression.

The official story that is largely told is a story ruled by white, heterosexual, economically wealthy men who act individualistically. This story in turn is supported by a white, heterosexual, male god, and continuously legitimizes the rights of those who oppress us and the duty of our submission.

I’ll never forget the words by the Argentinian singer Juan Carlos Baglietto in the song “Quien quiera oír, que oiga” [“Whoever wants to listen, let them listen”]: “If history is written by those who win, that means there is another history, the true story, whoever wants to listen, let them listen.” Our story is not one of defeated people—it is a story of resistance.

We have resisted to the theft of our victories, our heroes and heroins, our rebelliousness. To do that, we have oral and written accounts, poems, songs, spiritual expressions, embroidery work, our food. All that is part of what grassroots movements call mística.

Pursuing and appreciating the stories of fighters

One example of expropriation and resistance is women’s participation in the struggle for independence in Venezuela. This fact has remained hidden until the Bolivarian Revolution called for its review. The first pieces of evidence of their participation were there, in the stories people would tell, in quotes, sayings, poems, and even myths that have preserved the image of a Juana “La Avanzadora” [She Who Advances]. According to one of the myths around her, the location of Juana’s grave remains hidden so that it is not desecrated.

Based on these pieces of evidence, an investigation was launched. Now we know that there were women’s military units at the time. One of them was the Eastern Women’s Battery, a 40-strong unit led by Juana Ramírez, “La Avanzadora,” who received this sobriquet because she was one of the first to move forward upon the bugle call.

Memory, a Topic of the Future

Preserving our memory is an act of rebelliousness. We do that through collective building from our subjectivity, which reflects our principles, values, emotions, and pride, which makes us reclaim ourselves as deserving, dignified people. It is a strength for our movements to know where we came from, who we are, and what our actions have been over the course of history, as working women and peoples.

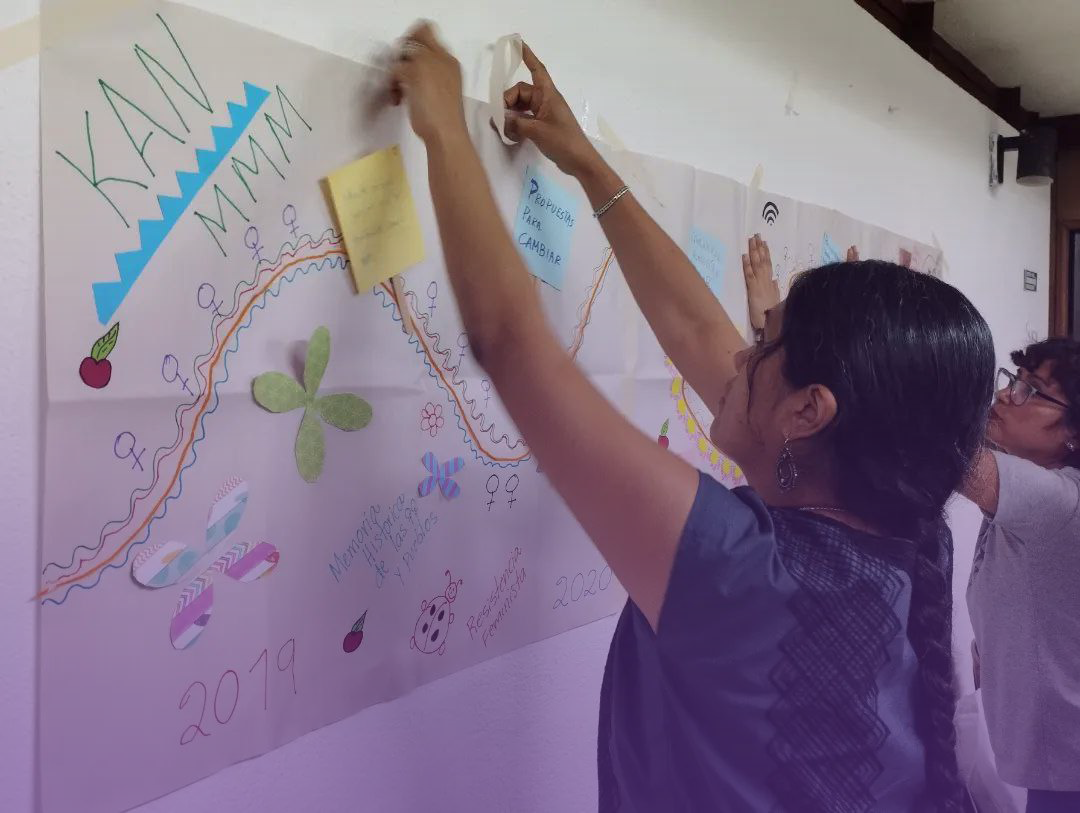

We have built memory by systematizing our journey, our proposals, and our struggles. And we do so not only through the written word, but also through photographs, graffiti art, poems, tales, legends, different cultural expressions and grassroots communications languages. We have built memory with mechanisms such as orality and grassroots creations, which we appreciate as legitimate sources.

We keep our memory and our story alive in our everyday lives, by constantly referring to the women who came before us, acknowledging and sharing their struggles, principles, contributions, and teachings. By making them part of our political reflection.

We must expand the understanding that memory is a building process that is not only about the past, but also the present, and it is fundamentally a matter of the future.

Here is a motto that is an exercise of memory, one that we also hear in our street demonstrations: “We are the granddaughters of the witches you could not burn.” We are also the granddaughters of the Black women you could not kill. We are also the granddaughters of the Indigenous women you could not rape.

Mística

The mística is a space that helps us to be grounded, here and now, in the beginning of a collective political activity. It connects us to our emotions and the power of being together.

It is a political practice that reclaims playful, aesthetic, spiritual, cultural, and subjective dimensions as fundamental parts of what we do as a movement, challenging the false patriarchal and capitalist separation between reason and emotion. It is a space of coherence, where we bring the personal and the political together—that is, we bring our emotions, sensations, and feelings together with our political action. It is a space that pursues and builds shared identity, subjectivity, and meanings in our collectives and movements. Místicas are spaces of reflection.

There is no such thing as one right way of carrying out a mística. But a mística must always be adapted to the territories, the cultural and political needs of the organizations, the goals of each meeting.

The mística, as well as memory, helps us consolidate “us”—that is, consolidate the sense of belonging to a collective that shares dreams and a worldview.

Alejandra Laprea lives in Caracas, Venezuela, and is an alternate member of the International Committee of the World March of Women. She is a member of the pedagogical working group of the Berta Cáceres Feminist School of the World March of Women Americas. This article is the outcome of her contributions in this process.