One year and a half ago, we published a report entitled “Lebanon: Hell in July”, to analyze what we were going through back then. Apparently, at that point, we didn’t know what hell was. While countries around the world were facing numerous economic and environmental crises as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic, capitalism, and global warming, Lebanon was hit by two more disasters: the economic collapse and the Beirut port explosion.

When we talk about “economic collapse,” it is different from the economic crisis the rest of the world is facing, in the sense that it’s a scenario that stems from destructive neoliberal policies that have ravaged the Lebanese economy after the 1975-90 civil war, pushing the country into a unproductive rentier economy that relies on the financial, touristic, and real estate services sectors. These actions were all taken with the approval, participation and for the benefit of all the political parties in power. According to the World Bank, this context has caused one of the three worst economic collapses ever recorded in the world, and the worst in Lebanon’s history. Neoliberal policies and the rentier economic system have led the Lebanese pound to depreciate by tenfold in one year—from 1,500 Lebanese pounds to the dollar, the country now pegs its currency at the rate of around 20,000. Another effect of neoliberal policies was the ruin of state institutions, the reduction of state subsidies, the encroachment of its wealth, and increasingly concentrated power in the hands of the ruling class, leaving the working class and the marginalized alone to face the Ghoul [a demon-like being that eats human flesh] of free market and merciless capitalism. In a country where the minimum wage is now worth around fifteen dollars, the now former deputy prime minister Zeina Akar, cabinet ministers, and the governor of Lebanon’s central bank (Banque du Liban) had a meeting last month to discuss the removal of fuel subsidies, thus raising fuel prices to twenty dollars per gallon.

The result of this collapse can be perceived through local and international media reports featuring humiliating queues at gas stations due to the shortage of gasoline and diesel. Additionally, the electricity and medicine shortages make life almost unbearable and work impossible in Lebanon, for those who still do have a job. Meanwhile, food prices have skyrocketed for more than 400 percent in one year. Also in one year, the working class has sunk below the poverty line. A report by the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for West Asia (ESCAP) showed that more than 55 percent of Lebanon has become “poor”.

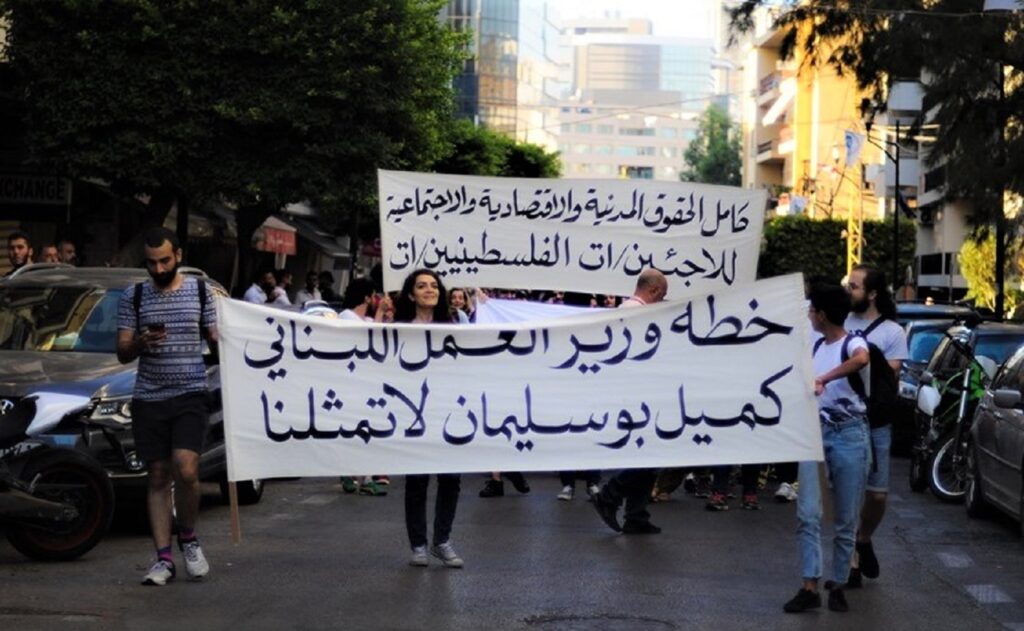

Concurrently, refugees were forced to rely more and more in international organizations and institutions. The living conditions of Syrians and Palestinians have deteriorated drastically during the last year, because the economic collapse has made it harder to find jobs and has contributed to creating more exploitative working conditions. Moreover, a large number of refugees live under pressure in overcrowded camps or neighborhoods with no infrastructure, safety, and basic sanitation. Another report, by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), makes it clear that refugees have three options in Lebanon: to either die from COVID-19, hunger or at sea, “illegally” trying to find a better life.

Meanwhile, while women bear the brunt of the pandemic and the current economic collapse, the struggle is even greater for women refugees and immigrant workers. Palestinian and Syrian women refugees in Lebanon have been stripped of their basic economic rights for years, while also enduring other forms of exploitation and racism, as international organizations reduced their aid to worthless food cards nevertheless. The country has been witnessing a huge injustice that affects migrant women workers, especially those employed in domestic work. In addition to being subject to the inhumane conditions of the Kafala system[1], these women are now left on their own as they face illegal expulsions under the pretext of the economic crisis.

On the other hand, the state infrastructure, which is responsible for securing a decent life and providing education, housing, and health care for the marginalized, is collapsing. In their paper “Housing as a Feminist Cause,” Public Works Studio showed how debilitating the access to safe housing has become for women in Lebanon and how invisible the right to housing is made, especially for older women, immigrant workers, and refugees who live in the areas that have been mostly affected by the Beirut port explosion. A report by the Housing Monitor revealed that 33 out of 110 eviction threats recorded in May and June were faced by women who live alone.

Health care wise, in addition to fearing a new wave of COVID-19 cases that could overwhelm hospitals, women’s sexual and reproductive health is also affected. The sexual and reproductive health care has been dismantled due to the lack of investments and the state’s unwillingness to cover surgeries and support women with medication, menstrual pads, and birth control. Actually, contraceptive pills have vanished from the market, and hygienic pads have become 20 times more expensive than they were last year. As surveys show, the economic collapse, the Beirut port explosion, and the COVID-19 pandemic have added up to many other crises, such as the 2019 wildfires, and occasional conflicts marked by racism, sectarianism, and regional and class-based discrimination.

This scenario has severely impacted the mental health of the population, especially that of women refugees. The collapse in infrastructure and the diesel fuel shortage have also impacted the infrastructure necessary for mental health care: the suicide prevention lifeline, an essential service to prevent the loss of even more lives, is now at risk due to the energy crisis.

In sync with the economic crisis, the ruling class—represented by cabinet ministers, legislators, political party leaders, bankers, and the governor of Lebanon’s central bank—refuses to change the country’s economic policies and to give back people’s access to their bank deposits. While the Lebanese pound is extremely undervalued to the dollar right now, authorities interpret reality with lies and surreal analyses, with arguments supported by misleading information: they blame refugees for the crisis, accuse the population of “keeping dollars” at home, and make up stories about a global conspiracy against Lebanon.

While it may seem like a victory for the working class, women, and marginalized communities, the failure of the negotiations with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) is not a good news: the ruling class is not offering better solutions. By adhering to the neoliberal capitalist model, the ruling class is trying to sacrifice more groups to protect its earnings and privileges, every day ruminating new lies, mobilizing its supporting base on sectarian, racist and classist terms.

There is no immediate solution for Lebanon, and those who already struggled with all forms of exploitation are the ones who will suffer the most. This means that the current collapse is a crisis felt by the entire society in Lebanon, but it’s the working class, women, the marginalized, and refugees who will feel these effects in multiple ways and to a greater extent. It’s a collapse that is destroying the forms and networks of protection, cooperation, solidarity, and steadfastness those communities have struggled for years to build.

Today, these communities are facing unprecedented challenges, and the state has vanished when it is needed the most, pushing the most affected population toward one thing: the exploitation of one another. The state is responsible for everything we are going through today, especially for destroying the unity and solidarity among the working class, women, the marginalized, and refugees.

[1] Kafala is an abusive patriarchal job contract in which migrant workers have to be sponsored by Lebanese citizens to stay in the country, ultimately becoming completely subject to their employers’ control. Employers have the right to hold their sponsored workers’ visa and become responsible for their legal status in the country, while being exempt from securing these workers’ labor rights, such as minimum wage, limited working hours, paid vacations, and paid overtime.

Jana Nakhal is an urban planner, a World March of Women activist in Lebanon, and a member of the Lebanese Communist Party.