In October we look back at the Russian Revolution of 1917. In the decade preceding the revolution and in the years of its consolidation, Russian women engaged in intense organization and mobilization, which inspire socialist feminism to this day. Revolutionary women introduced possibilities of emancipation, addressing matters such as motherhood, domestic work, prostitution, and equality as part of the inescapable transformations of a working-class revolution.

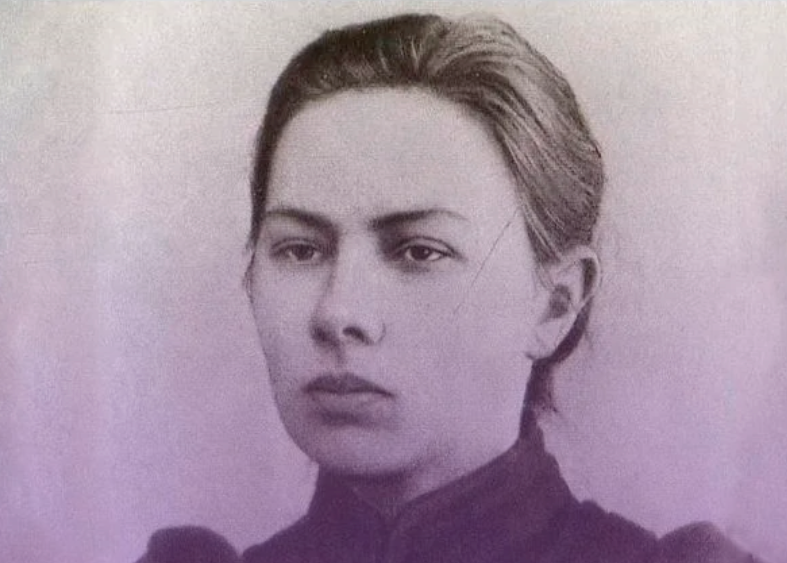

Nadezhda Krupskaya (1869-1939) was a revolutionary woman dedicated to many fronts. She was involved in the organization of factory workers; wrote feminist texts denouncing the oppression of working women; and contributed to their mobilization—in 1910, for example, on International Day of Women’s Struggles. She also worked for years promoting literacy for workers and helped formulate a socialist and emancipatory pedagogy. She was a member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party and took on different tasks over the course of her life. In face of the setbacks imposed on women in the 1930s, such as the dissolution of the Party’s women’s section and the restrictions imposed on abortion, Krupskaya expressed her trenchant critique, while being consistently committed to a society based on real equality.

To remember the October Revolution, Capire shares her writing “Religion and the Woman,” from 1927, where we can see how dedicated Krupskaya was to the challenges posed to organize and raise awareness among the working class, addressing how necessary it was to listen and engage in conversation about the people’s yearnings and needs, the subjective dimension that was extremely connected to women’s material living conditions, as well as the role of art in social change. More than a critique of religion, Krupskaya’s writing focuses on revolutionary strategies and practices to continuously build a new society.

Religion and the Woman (1927)

One cannot turn a blind eye to the fact that the religious sentiment is still strong and the sect movement is growing. Unfortunately, we at times are not attentive enough to this phenomenon.

The parish clergy (of the Russian Orthodox Church) have learned to be more subtle. They do not say a word against the Soviet power, following their approach with caution.

They say that, in the Velikoluksky District, Pskov Oblast, the nuns have set up a farming circle, and work is not lacking: they have won first place in the rural exhibition. They opened a red space and carry out their work there. Everything with prayers. The Poles (who live in border areas) were surprised by the priest: he organized a farming circle with forty peasants headed by a small producer. In the Sergachsky District, Nizhny Novgorod Oblast, where there are many Tatars, the mullah announced: “We are for the Soviet power. It proclaimed equality between men and women; a correction must be made to the Quran and the doors of mosques must be open not only for Muslim men, but also for Muslim women.” And so it was, Tatar women filled the mosques. Our clergy, unaccustomed to subtle methods of influence over their flocks, are managing to adapt to such a simple thing. In the town of Bogorodsk, Pavlovsky District, Nizhny Novgorod Oblast, where furriers who love canticles live, the clergy racked their brains: “What should we do? The citizens are no longer attending church as often.” Finally, they had an idea: they invited an opera singer from Moscow to perform at church and attracted virtually the entire local population.

The Kerzhenets Forest, which is now in Nizhny Novgorod Oblast, once harbored old believers, and their cells were wealthy (the money merchants from Volga gave them was not insignificant). The class on which the old believers relied has fallen apart and is dead, and they disappeared, but their remains are still scattered around Nizhny Novgorod.

In the Chernukha village, in the area of Arzamas, in the same oblast, in addition to the parish clergy, there are seven sects. In the tenth year since the revolution, they are sleeping in coffins! In other areas sects are also experiencing a resurgence: Evangelicals, Baptists. But we do not have to look very far for examples: in Moscow, the “Red Rosa” 1 weavers attend Evangelical sects. We must seriously look into all forms of contemporary sectarianism. Gone are the days when simply banning was enough to banish sectarian congregations. Now everyone is aware that we must tread a path that may be more difficult, yet it is much more effective.

First of all, we must carefully investigate the need that makes the religious sentiment emerge, assess the roots of contemporary religiousness.

Especially overriding for many people is the need to understand life around them, to connect different phenomena, to formulate some vision of a whole world for themselves, which can guide them to action.

Vladimir Ilyich wrote about how important it is to constantly educate the masses on a vision of a revolutionary world, therefore preparing them for revolutionary action. One thing is inextricably connected to the other, one feeds the other. And the time we are living is precisely the most significant time from the point of view of propaganda about the revolutionary worldview. In fact, only Communism can provide a more comprehensive and scientific answer to the yearnings that now emerge among many, many people.

The ground for propaganda is fertile. But inexperienced propagandists often limit the promotion of Communism to agitation, to listing events, to determinations; they try not to leave anything out but forget the most important thing: to unveil the connection between phenomena, to show, as they say, “what is what.” Propaganda is not enough—it makes what is promoted indifferent. Propagandists must listen extremely carefully to the demands of the population and carry out Marxist propaganda about the revolutionary worldview as fully and concretely as possible.

Regarding working and peasant women, the issue is even thornier. The Marxist worldview must be introduced to them in the simplest, most comprehensible manner.

Art here plays a special role. This, again, is something that the Catholic Church, for example, knows perfectly: beautiful canticles, statues, flowers, plays, all that captivates Catholic men and especially Catholic women. Regarding the influence art helps to achieve over the masses, priests are great masters. Religious art is art for the masses, often the only form of art to which the people has access. You do not have to pay to enter the Catholic Church. Our church greatly emulated Catholicism. Churches are adorned with icons, canticles are especially appealing.

The peasant woman, who from morning to night has her thoughts chained to domestic life, to her endless household chores, is happy to have the opportunity—at least on Sundays—to listen to a canticle, to see adorned figurines. The church offers her something that, after dull days of work, strongly captivates her. We now know well what drives art to church.

Well, in Velikoluksky District, Pskov Oblast, on the Holy and Great Saturday, they brought a traveling movie theater to the village. The people flocked in to watch the film, the church was empty. When the session was over, the same crowd, everyone who was in it, walked to the church to watch the blessing of the Easter cake. What made people go to church? A religious sentiment? No, it was the need for a spectacle.

Our art has not become popular yet, it has not become accessible for the masses as religious art is. And the Komsomol [abbreviation of “Kommunisticheskiy Soyuz Molodyozhi,” the All-Union Young Communist League] is correct when they pay special attention to this matter. They are absolutely right when they organize accordion competitions, when they get players to play beautiful songs, songs of the revolution on the accordion—an instrument that is close to the countryside.

The masses need music, they need art. Our art has not reached the bottom, it is still flying through the skies. And only it can supplant religious art.

But one aspect requires attention. Art is particularly captivating when the person is more than a mere spectator or listener—that is, when they take part in the mass action.

In the Catholic Church, churchgoers sing together; in ours, they make the sign of the cross, worship, fall on their knees, drag themselves under icons, take part in processions—in a nutshell, they come together in action for the masses. In essence, the drive for activities for the masses is healthy. And we must respond to it. We must organize choirs, make the entire countryside sing beautiful and excellent songs. We must promote walks, make them in such a way that they are not simply marches, but actions for the masses.

The carnivals, the Maslenitsa festivities [celebration marking the end of winter and beginning of spring] are nothing more than actions for the masses.

We must organize Communist carnivals and bring all working and peasant women to them. Art plays a major organizing role.

And right now, when the drive toward contact, toward collectivism, is growing, it is especially important to give the masses the possibility to meet this yearning in a rational way.

Above all, we must learn to wisely associate practical work and the promotion of propaganda about these very ideas.

By organizing farming circles, nuns and priests associated work with religious agitation and propaganda. We also must associate our practical work (farming circles, cooperatives, technical circles, etc.) with our worldview, let us impregnate all work with Communist spirit. Do we know how to do it? Poorly. We need to seriously study this matter.

However, we have learned something. I have written about a farming circle headed by a small producer, which was organized by a priest. The political educators in that village managed to have the small producer elected for the local council, and, later, the sessions of that council were scheduled on Sundays, at the same time as church service. As the group was making decisions on matters such as the village’s farming tax, which concerned the small producer, he started to attend every meeting and no longer went to church. The priest excluded him from the circle, and other six small producers followed him out, organizing their own initiative at the lyceum izba. 2 They were able to appoint an agronomist to be group director. The circle at the lyceum izba started to grow, while the one organized by the priest started to come undone until it eventually disappeared.

The struggle for influence over youth and women started to take new forms. We must organize to face this challenge, arming ourselves with our revolutionary Marxist-Leninist worldview.

And that shall be accomplished!

Published in Brazil in “A revolução das mulheres: emancipação feminina na Rússia soviética,” a collection organized by Graziela Schneider (Boitempo, 2017). Source: Религия и женщина [Religion and the Woman], in Antireliguióznik/Антирелигиозник [Anti-Religionist], Moscow, n. 2, 1927.