One of the main objectives of the International Feminist Organizing School “Berta Cáceres” (IFOS) is to develop methodologies and spaces for debate to construct a shared understanding of the feminist political subject. In this context, the feminist political subject is conceived as a collective identity rooted in the legacies of popular feminist struggles against capitalist, racist, and patriarchal systems. This definition is not static, it has been shaped through the School’s processes and the diverse perspectives of its member organizations.

The most recent process of reflection and development took place through a series of debates with representatives from the Continental Journey for Democracy and Against Neoliberalism. This coalition includes activists from the World March of Women (WMW), Jubilee South, Friends of the Earth Latin America and Caribbean (ATALC), the Latin American Coordination of Rural Organizations (CLOC-Via Campesina), Grassroots Global Justice (GGJ), ALBA Movements, and the Cuban Chapter of Social Movements. Throughout 2024, activists held monthly discussions about the understanding and use of the feminist political subject as a category in the organizations’ work and the key elements that define it.

It was therefore necessary to develop a methodology for systematizing and synthesizing these debates, one that would reflect the diversity of the topic and the political collective that makes up the School. Carmen Díaz, an activist with the WMW and a member of the IFOS methodology committee, along with Ana Karen Navarro and Nátaly Nuño, students at the Jesuit University of Guadalajara, participated in this cycle of debates with the task of producing a synthesis of the process.

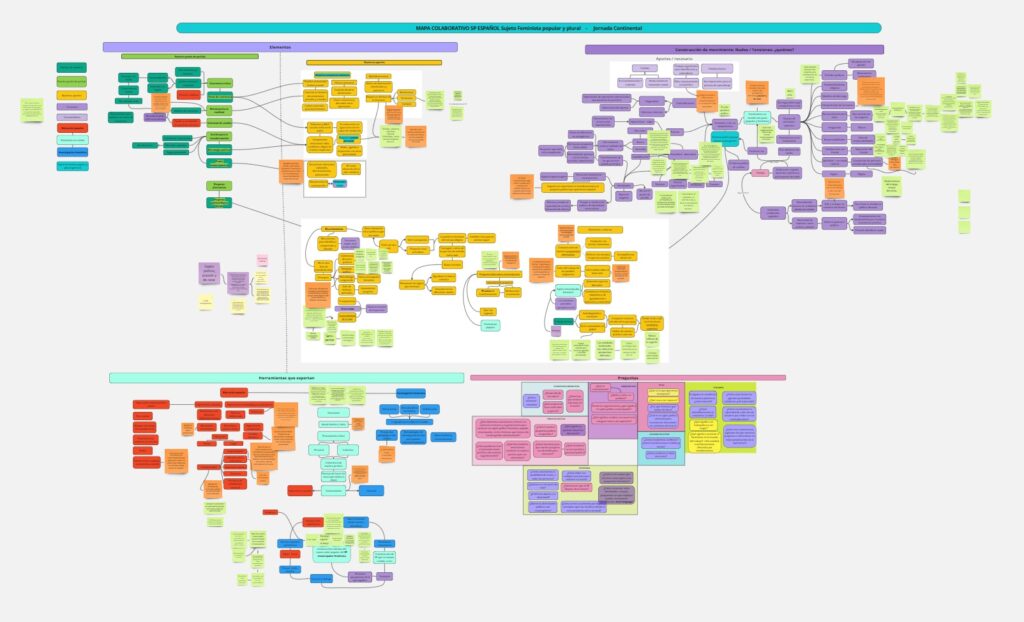

To capture the diversity and collective nature of the debate, the team proposed creating a mind map to organize the various aspects and complexities of the feminist political subject. “We proposed using mind maps because, as students, they were incredibly useful to us when presenting more complex information. We shared the idea with the group to get their feedback; if it wasn’t a good fit, we would have found another way. I think this approach aligns with feminist grassroots education, which involves experimenting and practicing. That’s how we discovered what worked and what didn’t,” explains Nátaly.

The map was presented for the first time during the in-person edition of the School for Facilitators, held this August in Honduras. A physical copy, made on paper and poster board, was displayed during one of the sessions. Additionally, the digital version is available for participants of the School to explore, discuss, and provide feedback, ensuring the process remains dynamic and ongoing.

Sandra Morán, coordinator of IFOS, frequently emphasizes that a key strength of this feminist popular education process is its ability to systematize and document debates as collective memory. On this topic, Carmen adds: “One of the problems we face in movements is that, while we have accumulated a wealth of knowledge, experience, and wisdom, we have very little time to systematize it. What’s interesting about the maps is that they are dynamic, and their connections can be reconfigured depending on what we want to explain. The contribution of this process is that we now have a memory of these discussions in a format different from what we usually use, like reports, which are harder to consult.”

This entire cycle of debate and synthesis stems directly from the documents produced during the first edition of the School in 2021. According to Carmen, the goal is to reclaim the knowledge accumulated from the process: “The idea is for this to allow us to conclude the year with a new document, that continues to enrich the theoretical framework, one that makes sense to us when discussing movement-building and the feminist political subject.”

The systematizers’ participation was a practical exercise in feminist methodology, rooted in collective discussion and collaboration. It was essential for the synthesis to closely reflect what had been discussed, avoiding the temptation for the final perspective to become that of the writer alone. “I believe this is a key challenge for anyone tasked with synthesis: how to make it concise enough to avoid triggering another hour-long discussion, but also broad enough to allow unresolved issues to be revisited in future debates. What our comrades told us was very encouraging: ‘We recognize our words, concerns, and contributions in these systematizations,’” Carmen shares.

Karen describes the process as a hands-on learning experience, especially when navigating unfamiliar topics and discussions. When tensions arose within the group, their initial response was to discuss among themselves in search of solutions. “But in the end, we realized that the purpose of creating this synthesis wasn’t to untangle all the knots that had surfaced, but rather to highlight that they existed,” Karen explains.

Another significant challenge was ensuring language justice in a circular process of debates and synthesis involving participants who spoke various languages. Nátaly highlights how understanding the meaning and importance of language justice transformed her perspective. “When these issues resonate with you, they gain a depth and importance that go beyond concepts or theories, becoming a political commitment. For me, that was the most significant moment—when we became truly aware of it”,” she shares.

The creation of the map introduced new theoretical and methodological possibilities for shaping the political subject based on the experiences of social movements. The map’s color categories represent the themes of each element. For example, the green elements address the starting points identified during the drafting process. The purple ones indicate aspects of movement building, while the pink elements present questions for future reflection. These elements highlight contributions from feminism to the concept of the political subject, discussions on popular education, feminist research, and how these two intersect, among other topics.

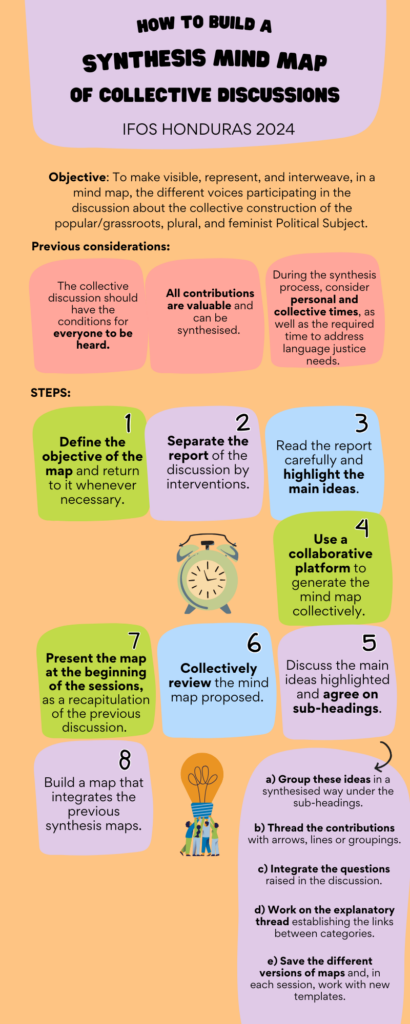

The map is not a final product; rather, it serves as a resource to inspire the development of diverse materials for feminist popular education. The team shared that the final stage of this process will be to collectively decide how the information will be presented and through which narrative possibilities. Karen, for instance, envisions creating podcasts, infographics, texts, and other diverse formats aimed at “translating this information for those who were not part of the entire process.” Some discussions about expanding access to the map and its content are already underway. Furthermore, during the IFOS for Facilitators, Karen and Nátaly shared an infographic with basic instructions on how to create a mental map, allowing this tool to be replicated.