Social movements that struggle for food sovereignty and build agroecology denounce and reject the offensive taken by corporate power against food and nature, represented by the United Nations Food Systems Summit (UNFSS).

This summit is the result of a deal between the UN and the World Economic Forum and it’s a strategy adopted by big transnational corporations to move against food. It’s organized through a “multi-stakeholder participation” model, which puts transnational corporations at the center of political decision making. This consolidates the privatization of politics and the corporate capture of the UN system.

The summit bypasses the processes and forums built over the course of decades with the participation of peasant and Indigenous movements, disregards the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Peasants, and directly attacks food sovereignty. This is why La Via Campesina is calling for a boycott of this summit with the slogan: “Not In Our Names!”

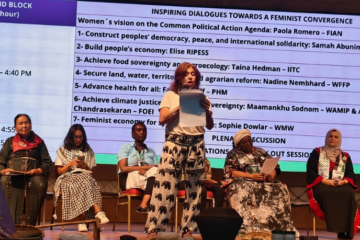

The women with the World March of Women, Friends of the Earth International, FIAN, and La Via Campesina have denounced[1] the offensive of the market that grabs nature, territories, and food. Several fronts of racist and patriarchal capitalism and colonialism converge on this offensive. The appropriation of food systems, agriculture 4.0, green economy, and the so-called nature-based solutions are all connected with each other, with digitalization in the background.

Once again, the economic elites use the profound crisis we are facing to justify their false solutions, which further incorporate nature into the financialized cycle of capitalist accumulation.

Our resistance comes from the criticism and affirmation that the true solutions are the agriculture historically carried out by the peoples, peasants, Indigenous communities, and women.

The Place of Food and Nature in the Capital-Life Conflict

Food cannot be seen as an isolated thing, as it is at the center of the organization of society and our shared lives. When transnational corporations organize to control the entire food system, they want to control society and life.

Women warn that what’s at stake here is a change in the sense and meaning of food and nourishment. This is related to an ongoing overhaul of the food industry, in which ultra-processed food products display “fortifying” features as a solution. They add “more calcium” to milk or substitute sugar for stevia in their Coca-cola products, as if being healthy was just about that. “Nutritious” then becomes something that is measured through the fragmentation of substances that can be produced in a lab, in an advanced process that makes everything we eat artificial.

This is why we must be watchful in our comprehensive analysis, understanding the connection between land grabbing, the displacement of peasants by agribusiness, and the investments in synthetic and molecular biology, for example.

Bill Gates is someone who represents this corporate collaboration toward the control over food systems: his foundations and investment funds are buying huge patches of land while also investing in pesticides, seed corporations, intellectual property, apps to put small farmers and peasants under their digitalized control, plant-based protein companies, and others. It is no coincidence that the head of the Food Systems Summit is also the head of AGRA (Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa), a Gates-funded initiative.

A key aspect of the feminist reflection on the dangers of this Summit is the relationship between food and nature. A framework for this relationship is green capitalism. By reducing the complex environmental crisis to climate change, green economy projects aim to create new markets that are included in the logic of speculation and financialization. It’s the carbon markets, of which REDD+ is a point of reference, and ecosystem markets established, for example, with payment for environmental services. Investment funds that impact “climate-smart food systems” are examples of how agriculture is incorporated in the green economy cycle.

The political battle around food and nature includes exposing how these two different kinds of logic are not compatible: on the one side, sustainability and caring for life; on the other, capital accumulation (including data accumulation as capital). Each is irreconcilable with the other, with completely different concepts of nature.

Diversity and Complexity Against Reduction and Homogenization

Apps, drones, and sensors are marketed to make farming easier. But there are corporate tech packages behind them. These technologies are not neutral. They are meant to fragment and reduce everything down to binary data, homogenizing and appropriating living things.

Algorithms speak the language of agribusiness. All they know is one form of farming (row crops), modified and patented seeds, and pesticides. This kind of agriculture has nothing to do with agroecological farming, which is complex and diverse.

Datafication aims to make life artificial, accelerate paces disrespecting the time needed for the regeneration of nature, bodies, and caring for what is living. It does so by concealing how much we depend on each other and on nature.

At the Food Systems Summit, Bayer, Syngenta, and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) – an international organization with more than 200 companies working on sustainable development – push the conversation on “opportunities to invest on soil.” Their views reduce soil to a carbon sink. On the other hand, agroecological farmers see the soil as a living, diverse organism. One of women’s contributions for agroecological farming is caring for and nurturing a fertile, rich, complex soil.

Expanding the conversation, sisters denounce the rhetoric of corporations that come to territories promising to invest in “idle areas.” In Mozambique, for example, companies say that “idle” lands are those that are not used for machamba (crops). But there is no idle area in the territories of communities. These are the areas where women get medicinal plants from, where rituals and prayers take place, and where communities find strength to resist and live a shared life. They are denied these vital areas, which are seized in the name of devastating progress. To reclaim these territories and uses is to acknowledge ancient practices and knowledge that passes on from generation to generation – practices that have been criminalized by green economy projects.

Promoted by transnational organizations such as the World Wide Fund (WWF) and The Nature Conservancy (TNC), environment conservation policies carry a deeply colonialist form of environmental racism. They force communities out of their territories in the name of environment conservation, as if the ways of living of traditional communities were opposed to nature. But these are communities that have historically cared for and nurtured biodiversity.

Feminist Agroecology Cannot Be Captured by Corporations

One of the great dangers of the Food Systems Summit is to establish the necessary frameworks to include agroecology in the green economy cycle . Based on ideas of “net zero” and nature-based solutions, these actors have been talking about expanding the carbon market to mangroves, oceans, and agroecology, as well as expanding the financialization of nature. Agroecology is about practice, science, and movement. It cannot be appropriated in a fragmented, selective way, let alone alienated from the political actors that make it possible. There is also a battle about what is regarded as science and technology at the Summit. Corporate power aims to legitimize an anthropocentric, androcentric science[2] of food systems, which is connected with the interests of corporations and the reorganization of the language of capital.

Agroecology is strategic knowledge. Women reclaim the peoples’ different forms of knowledge and technology and denounce epistemicide, which is the destruction of the wisdom and culture of racialized peoples.

Greenwashing and purplewashing are articulated into the corporate agenda of the Summit, using women’s empowerment from a neoliberal perspective as a cross-sectional pillar. This leads to slogans such as “nature employs women.”

In blue carbon projects for oceans and mangroves (such as Vida Manglar, in Colombia), they advertise that women are employed as guardians. These projects are based on public-private partnerships, which lead to land grabbing and displacement of communities. This is why the movements have decided to call them “nature-based oppressions and exclusions.”

When companies first arrive in different territories, they are met with communities that face precarious conditions and the lack of public policies. They come along offering compensations that will further include communities in markets, providing more technified tools for crop and livestock farming, making communities depend more on the owners of the technologies. One example shared by sisters from Brazil is the set up of fish farming tanks in Indigenous communities, a compensation offered by REDD+ projects. Previously, these communities have always fished in rivers, which now are often polluted by mining and other operations. Little by little, corporate power breaks up local economies and increases the barriers to the peoples’ self-determination and sovereignty.

Women challenge this offensive and pledge to affirm their practices and movements: the diversity of nature, its multiple roles and relationships. It’s like our sisters say: a woman farmer’s backyard has more diversity than any bioeconomy program carried out by pharmaceutical companies.

Tearing down the rhetoric that incorporates women and agroecology into capital is a task undertaken by grassroots feminism in the struggle for food sovereignty.

This task is connected to the affirmation of agriculture by women peasants and traditional peoples, through the diversity and complexity of agroecology. This practice, science, and movement is about fighting for the meanings of territories and challenging private property – of land and mind –, asserting free territories and technologies.

The people’s counter-summit is a moment when different social movements will converge and build more power to the peoples against corporate power.

[1] This article was written based on the synthesis of a workshop held on July 6th, with the participation of sisters of the World March of Women, Friends of the Earth International, FIAN, and La Via Campesina.

[2] Anthropocentrism views humans as the center and top priority of any analysis. Androcentrism is grounded in and based on male experiences, extrapolating them as though they were a point of reference for all human beings.