From farm to table, agrifood systems are becoming increasingly digital across the planet, and their impacts are unclear. While we could think that, because going digital requires a high-tech package, only industrial agricultural systems do it, this has also been on the rise in countries in the South and areas of family and peasant agriculture, with false promises of higher efficiency and information to improve production.

Many questions emerge with this new wave of technology in the countryside. What is it and what does it mean? What impacts does it have on the peasantry and family and small-scale agriculture? Here I share a document with examples of possible impacts and reflections on the matter (https://tinyurl.com/ytrkzw76).

In Mexico, the world’s biggest seed and pesticide brands, like Bayer-Monsanto, BASF, and Corteva (a DuPont-Dow merger), launched new digital agricultural platforms between January and May 2022, selling “services” to farmers. They are adding up to others that have been around in recent years and they have also been implemented in other Latin American—especially in Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, and Colombia, all countries where these transnational corporations rule the agribusiness markets and were able to impose huge areas of transgenic crops and the use of pesticides.

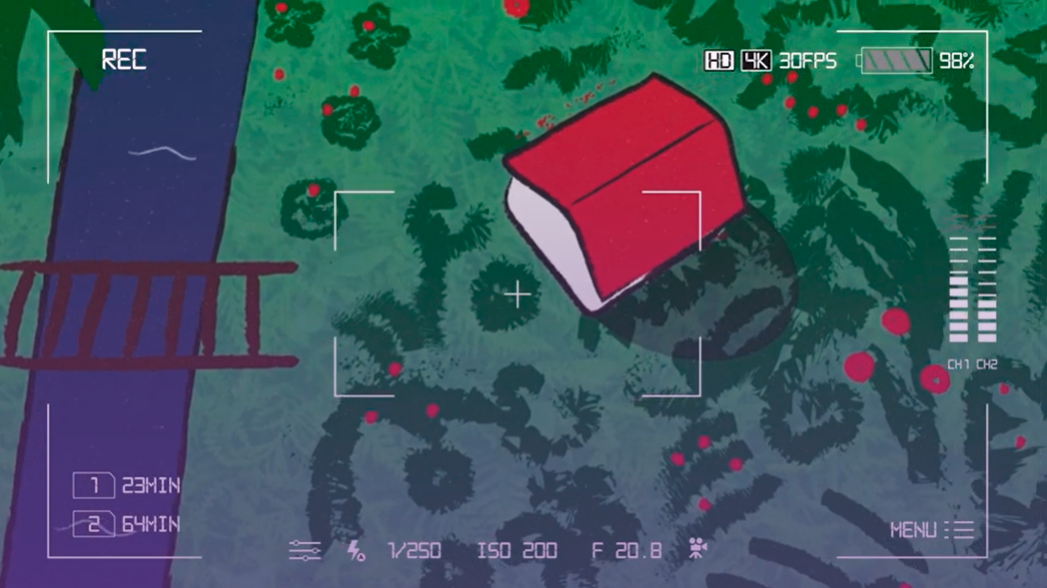

Basically, to join their digital platforms, farmers must agree to a standard form contract. Then, through systems that could include drones, satellite resources, or pictures of crops taken by the farmers themselves with their phones and uploaded to the platforms, the companies record their field data about things including soil, humidity, seeds, production, crop diseases, invasive plants, and bugs that can be considered pests, vegetation, forests, etc. They store and process this information in computer clouds owned by Big Tech companies and provide “advices” to farmers regarding what to use, how much to use, and where to use certain products on their fields. Usually, the contracts guarantee results only if farmers agree to use the companies’ own seeds and pesticides.

Bayer—which bought Monsanto and became the owner of Climate FieldView, one of the most popular platforms of its kind—announced in 2022 an agreement with Microsoft Azure (cloud computing) to not only operate in the countryside, but also digitally follow supply chains. Microsoft has also offered the FarmBeats platform. BASF launched in Mexico the Xarvio platform, which pledges to detect weeds, pests, and local diseases in major crops based on cell phone pictures. Corteva includes in several of its platforms—such as Granular and Milote, with similar features—a new feature to measure “carbon footprints” in rural areas. This way, Corteva and Bayer engage in a foray to get potential carbon credits from farming soils, an issue that raises several concerns for its negative effects.

The implementation of digital and robotic technology in rural areas goes hand in hand with agreements and mergers between the biggest agribusiness companies—who produce and trade seeds, pesticides, fertilizers—with agricultural equipment manufacturers and Big Tech companies.

Each stage of the industrial agrifood chain is run by few companies: 5–10 companies in each industry control more than than half of the global market. The greatest change in the agrifood industry in recent years was the emergence of US Big Tech giants (known as GAFAM, an acronym for their names before trade name changes: Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple, Microsoft) along with the Chinese companies Alibaba and Tencent.

More and more, the companies that call the shots regarding agrifood production, supply, and markets do not have a background in or knowledge of the industry. The fact that the main interest of transnational agribusiness is not food production, but profit, gains new meanings as equally or more unscrupulous companies join in, with the immediate goal of collecting as much data as possible to sell information and forms to manipulate food production and consumer behavior among big social groups.

What Shoshana Zuboff called surveillance capitalism has, therefore, its “surveillance agriculture” version. What we eat, how and where it is produced and marketed are key information about rural areas and society at large.

Therefore, digital platforms are not only targeting big landowners and industrial farming. To collect more data on the countryside and food processes, there is a vast range of trade offers and features to engage small-scale and peasant farming, which represents the majority of the rural population.

Introducing digital platforms solidifies the dependence of all scale farmers on big companies through contracts that force them to use their products and farming management. This is something that already happened in the past, but as resources go digital, it significantly expands. Moreover, now the new business is that oligopolies take an infinite amount of data points about each field (including land, forests, water, territories), gaining knowledge of production, seeds, soil and crop management, marketing, and consumer eating habits. Far from providing “services” to peasant communities, they subject these communities to massive extraction of information which, once “datafied” and interpreted by their algorithms, becomes commodities that allow companies to make more profits and further control them.

___________________________

Silvia Ribeiro lives in Mexico. She is a Uruguayan researcher, environmental activist, a member of the Action Group on Erosion Technology and Concentration (ETC Group).