Feminist grassroots education methodologies integrate form and content, respecting different paces and caring for the collective building of knowledge that drives the struggle. Their starting point is the individual and collective experiences of resistance and organization. These are the principles of the Berta Cáceres International Feminist Organizing School, which held on April 5th a technical training workshop to address the tools it will use and a session to introduce and welcome participants.

Sharing knowledge and technologies and bringing to light the work that is necessary to conduct an online International School

In order to connect to and take part in the International School, some women who live in ancestral indigenous lands and communities of African descent territories had to travel to the city to get internet access. Some used phones, while others used computers. Learning how to use video conferencing tools is a challenge that participants have taken on, and a continuous process to take part in the school and bolster women’s organizing everywhere.

During the workshop, all tools that will be used were introduced, one by one: video conferencing tools, applications to collectively record the discussions, the space of memory in each meeting.

Translation is a continuous challenge when building international and internationalist movements. Language justice is a principle and a practice for the School. The translation team who is taking part in this whole process — working with the English, Portuguese, French, and Spanish languages — was introduced and everyone was able to meet those whose voices make it possible for participants to understand each other and share and build knowledge.

Making the invisible work of translation visible and making language justice a political principle is a way to acknowledge the necessary work and collective commitment to this principle: having to speak more slowly, pausing between sentences, avoiding acronyms, among other fundamental practices to promote active listening and understanding at such a diverse School. The school’s working languages are not necessarily the native languages of participants, which poses even more challenges and requires an even greater commitment. Arabic-speaking sisters pointed out that they will also organize Arabic translation practices for their time at the School.

When we talk about technologies, we are not talking only about digital. Being connected for three hours straight during each meeting, it’s important to bear in mind that, behind those screens, there are bodies that need to eat, hydrate, stretch. Participants joined different committees and working groups to share the School’s assignments: activities to energize body and mind, grounding spirituality, syntheses, and reports, as well as parties. Participants also made a commitment to record the political and methodological reflections emerging from every meeting in journals, which will be fundamental to later organize political education processes in each region.

Who are the participants of the International School and what are their struggles?

School participants include 132 militants from different peoples and places in at least 39 countries and territories: Zimbabwe, Zambia, Venezuela, Uganda, Turkey, Tunisia, Tanzania, Sudan, Somalia, Democratic Republic of the Congo, United Kingdom, Kenya, Quebec, Portugal, Porto Rico, Philippines, Pakistan, Palestine, Nigeria, Mozambique, Mexico, Morocco, Lebanon, India, Honduras, Netherlands, Haiti, Iximulew/Guatemala, Galicia, Basque Country, United States, Cuba, Ivory Coast, Chile, Canada, Burkina Faso, Brazil, Bolivia, Algeria. We make sure to write “at least” because many of the struggle these women wage include reclaiming and acknowledging the territories of their peoples, whether it’s the demarcation of ancestral indigenous lands or communities of African descent, whether it’s the acknowledgement and promotion of the memory of the peoples from every place that has been occupied by colonization.

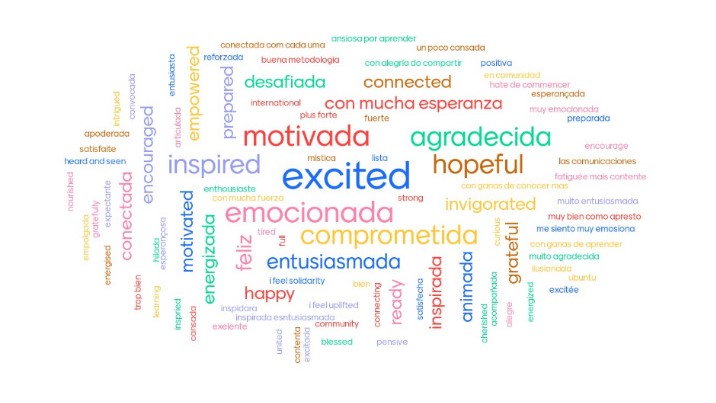

Every participant brings their struggles and views to the School, and they are shared during this meeting in fourteen base groups conducted simultaneously, divided into the School’s four working languages (Portuguese, Spanish, English, and French). The struggles are multiple and they are diverse, but they have points of contact and connection, bound in solidarity and internationalism.

They build a feminist, anti-racist school with solidarity as its practice, as a horizon and as a program to change society.

The women who take part in the School are part of processes in which they struggle and defend territories and resist against extractivism, contamination, forced displacement, forest and land grabbing, real estate speculation in the cities, colonialist occupations, and capital frontier expansion leveraged by transnational corporations. The women asserted the self-determination of the peoples and the collective ownership of ancestral indigenous territories and territories of communities of African descent.

These struggles are articulated with bids for environmental and climate justice, and they challenge the pipelines that cut through territories and communities, the dams and hydroelectric power plants that privatize rivers, and the walls that ban free movement, dignity, and rights. Sexual and racist violence intensifies in big extractivist projects. The participants face violence and femicide, trafficking and exploitation, genital mutilation and abortion bans. They state their autonomy over their bodies and diverse and dissident sexualities; they struggle so that women and LGBT people can move freely and safely.

These women build food sovereignty as a political project, based on practices and strategies such as agroecology in rural areas and cities, and the defense of traditional seeds as peoples’ heritage.

In different parts of the world, School participants face criminalization, surveillance, political killings and persecution, and they find things in common and expand their anti-racist struggles against mass incarceration and prisons. They build struggles for peace in their countries and the world, facing the tribulations of war and armed conflicts, which are associated with the violent dispute over common goods and nature.

School participants are engaged in the resistance against the rise of the far right and fascism, against coups and authoritarian political forces that aggravate racism, misogyny, and heteropatriarchal dynamics that impose motherhood and domestic work as responsibilities exclusively shouldered by women within their families. School participants struggle for the rights of domestic workers; they face poverty and articulate women’s everyday experiences as strong criticism of neoliberal and adjustment policies, of debt imposed by financial institutions, of free trade agreements, and patents that pose an obstacle to public health. They are engaged in defending migrant people’s rights and work in community-based organizations so that communities who are excluded from the most basic rights have access to food, care, and healthcare. They stand up for public services and the reorganization of domestic and care work that make the sustainability of life possible. They take part in political processes so that the sustainability of life is at the center of legislation, including constitutional processes.

As part of their organizational practices and alternatives with which they march on, School participants provide a blunt critique of the violent development model spearheaded by transnational corporations. And from there, they build a feminist, anti-racist school with solidarity as its practice, as a horizon and as a program to change society. They reclaim grassroots, indigenous, peasant feminism. They are anti-capitalist. They build mutual support initiatives, and practices to care and heal bodies and nature, collectively and self-organized in their communities, facing racism and colonialism, defending body-earth-memory. They restore and reclaim ancient languages and wisdom, while building feminist grassroots communication tools. All these strategies are found in the building of emancipatory political subjects, and they are the starting point for women who will, until July, make this International School a milestone for building grassroots feminism. Follow Capire to learn about the syntheses articulated in each meeting.