On Sunday, 31th of July, feminists, and queer folks went to the streets of Beirut, protesting against situation that had us bottled up since the end of the 2019 uprising. The protest was inevitable, and erupted a radical discourse opposing the violence, alienation, and the power of capital dominating queer/feminist scene(s) in Lebanon. This is not to claim that we “taught the system a lesson”, nor that we eradicated the neoliberal cooptation of the feminist movement, especially not in a still-very-colonized country that happens to be just north of Palestine, west of Syria, and going through a major economic collapse. But the demonstration – the way it was organized, how we got together – felt pivotal at the time, and in retrospective, it is still an experience to learn from, hold on to. It was the start of something, and a testimony of great feminist values and grassroot intersectional approach building in the scene.

Overview of the Lebanese context

As one would expect, under the Lebanese system – in its social, political, and economic sense – queerness and gender are motives for alienation and violent practices. At the same time, racism is structural and flourishes during the crisis. A few incidents were particularly triggering before the demonstration. Since the Lebanese civil war (1975-1990), “opposing movements” were torn between politicized organizations/parties and NGOs. With the Leftist groups’ failure to support the battle of women, and their refusal to adopt, to this day, a proper intersectional approach for labor rights, the arena was emptied for NGOs and neoliberal organizations. Even with the recent modest attempt of of leftist parties and youth movements to include some feminism in their discourse, LGBT+ were excluded. The pretext was priorities. However, homophobia, transphobia, patriarchal conservatism, and maybe the fear of the Right’s reaction to such demands, were behind this belated discourse. The impairment of our so called Left gets louder when we grow more conscious of its inaction towards refugees and immigrants’ rights.

Stand against violence, stand against neoliberalism

The protest happened after a long period of recovery from the failure of the attempted revolution (2019-2020). Moreover, we’ve been hearing about a series of murders and abuse happening to women, strangers, friends, and acquaintances. Others were victims of legal practices denying them their right to maternity, and more. Then, conservative extremist Christians organized violent attacks on many events in Beirut discussing or addressing queerness. The Ministry of Interior Affairs thought the solution to end the violence is to issue a statement prohibiting any meeting, any event “promoting aberration”, as they put it.

In reaction, some well-known NGOs called for a protest in support of LGBT+ “visibility and pride” in front of the Ministry of Interior Affairs building on a Sunday, disregarding the unsafe context they were organizing it in. In addition, a day earlier to this call, we learned that Syrian farm workers in Beqaa had been beaten and tortured by their landlord — or, if you may, the master — in an effort to coerce their exploitation for profit. The same NGOs that were so incensed by the LGBT+ agenda made no mention of this systemically rooted incident.

The outrage over these events was molded with the outrage at how they were handled and the dreadful double standards that were shown by NGOs, considering that the latter is a political pattern. Many NGO leaders, especially those residing abroad, are unaware of the daily struggles, nor how it feels to be constantly scared for your life. Additionally, the decisions are made based on what the funders want, mainly “pride”, not the necessities of the people. Furthermore, even some services they offer lack continuity, reliability, and basic decency in talking to people, such as promising a homeless trans person housing funds and not returning their calls.

What hapenned to the very sudden protest was that only Lebanese straight cis people were going, as the rest of us were scared to be harassed. We – among us members and workers at these NGOs – voted against it and urged them to cancel so that we organize one that speaks to our reality.

Our demonstration: how we got together, how it went

We invited trusted people through our connections: the initial message spread quickly from one circle to another as this is a small country. It was both an open and a non-public invitation. We met in secret because conservatives were lurking and the police were still working by the statement. The first two meetings were solely to discuss the concept of “safety over visibility” in all its facets and establish it as our priority.

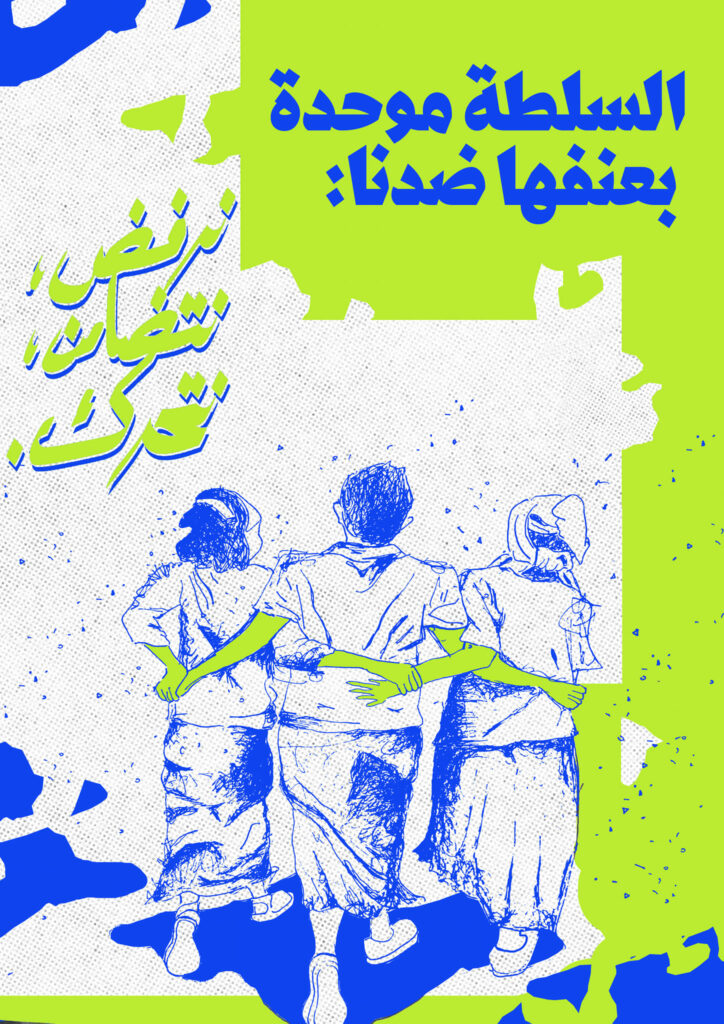

Despite the challenges, significant efforts were made to involve as many people as possible in the conversations and decision-making during the month of July, using a variety of communication methods (face-to-face, online, on WhatsApp), and repeating meetings if needed. We called the media pages Taharok Nasawi (feminist movement in Arabic), and the event “we refuse, we unite, we move”.

We made an effort to be as horizontal as we could; for instance, we repeatedly voted on the movement’s official position statement. The allocation of roles and responsibilities throughout these meetings was done with considerateness, and people put their hearts into the writings, infographics, coordination, and ensuring social media coverage. And the way we discussed, to respect, constructive criticism and kindness, it hardly felt like work. A comrade, politically active since 2013, expressed that these meetings has been the least tense most productive ones she’s experienced, and this is worth mentioning in a feminist political article.

The discussion around the protesters’ safety was a serious one. We feared that the police would detain and administer drug tests to persons who lack proper documentation, refugees, immigrants, and LGBT+ people.

We established a safety committee, and came up with tactics: if you’re privileged and the police attacks, throw yourself in front of your less privileged comrade. That’s a rule. We meant for people holding flags or at risk of harassment to be at the center of the protest surrounded by those who aren’t, and backup plans if medical treatment, or legal assistance were needed. Attempts to decentralize the protest were really serious, but we lacked the tools and the social and economic infrastructure.

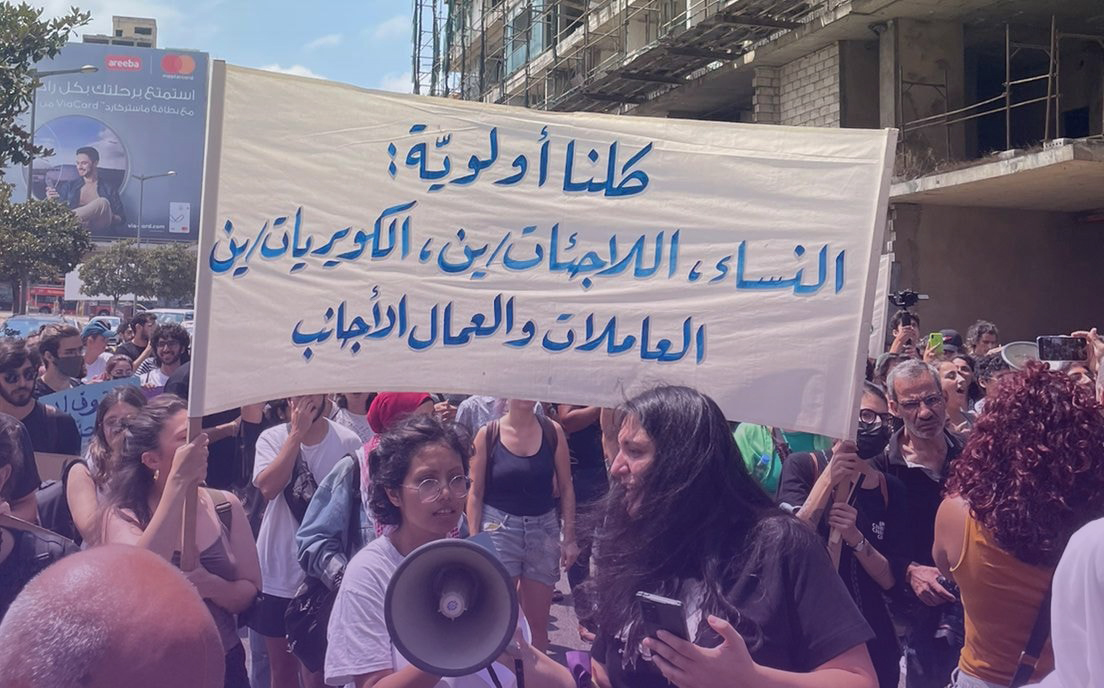

The issues discussed were carefully chosen, and they covered far more ground than simply objecting to the statement given by the Ministry. Correlating economics and gender was one of the issues, as was rejecting the state’s violence discourse and stating that everyone, including refugees, queers, and workers, are a priority (as opposed to right voices denying the right for food to refugees under the crisis). We highlighted that acts of violence are systemic, not individual, and that the social fabric paves their way. We also asserted the inclusion of queer demands in the feminist struggle inextricably. Additionally, we were extremely careful to include the presence of those who couldn’t physically attend the protest, due to the cost of transportation, or because they’re denied the freedom to move about. One of our mottos was that we were protesting for those who couldn’t be with us.

The demonstration itself, starting from the Ring Bridge, going through downtown Beirut, gathered a large number of participants (more than expected). It expressed, both through banners and chants, a beautiful array of radical, inclusive and detailed demands, while everyone was kept safe.

Images and videos from the demonstration, while keeping in check the safety and anonymity of individuals who chose to stay unknown, were able to send a message to those who have felt alone, excluded and stigmatized in the last period in Lebanon. We hope that this will help not only building a coalition between the different marginalized groups, but also break the grip of the mainstream discourse on the lives of those who feel rejected and disenfranchised.

The World March of Women in the demonstration

Sisters from the World March of Women were among the organization’s earliest participants; we were part of the big circles that got the message and spread it. We made sure to put our all in the media coverage. Furthermore, it’s important to keep in mind that such moves don’t just happen overnight; rather, they’re the consequence of years of effort and accumulation, and we can’t claim exclusive responsibility for this.

What’s next

It was important to us that this new movement continue. We brainstormed concepts while also maintaining the communication groups and media pages. We came back together to plan a second protest on October 2nd in solidarity with Iranian women. With many yet to come.