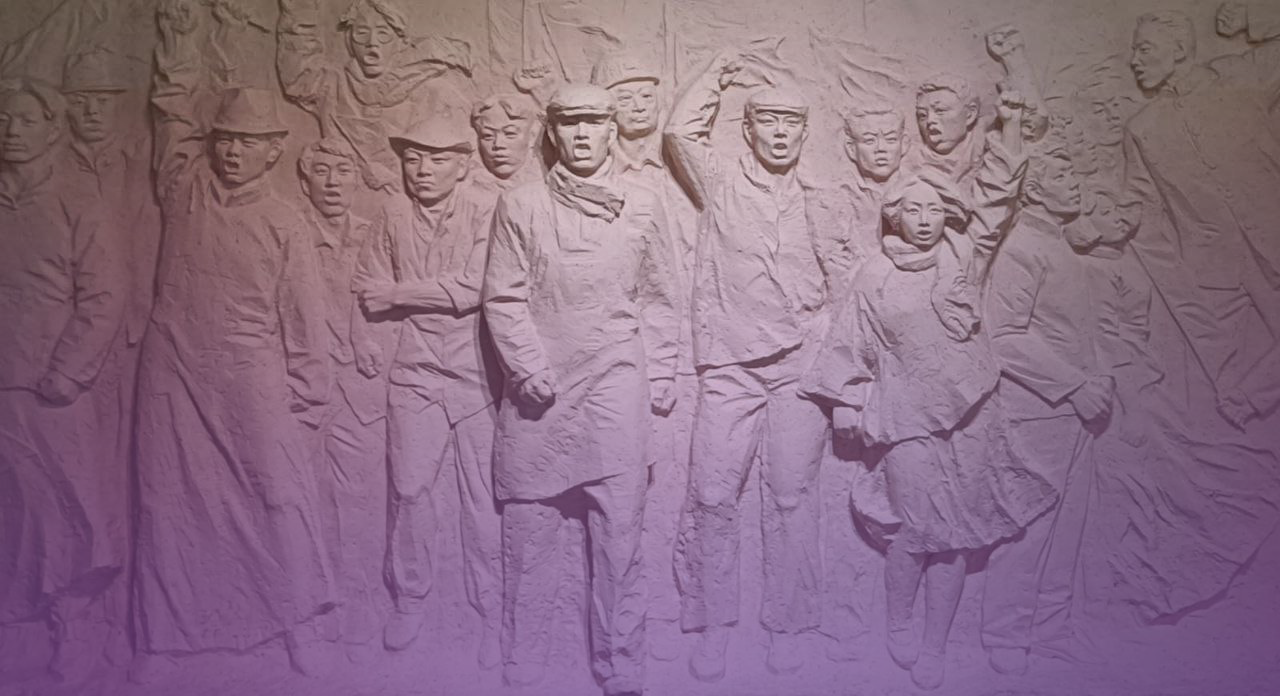

On May 4th, 1919, thousands of young intellectuals came together in Beijing two days after the news that the Chinese territories of Shandong, which were then under German control, would be transferred to Japan. The change was negotiated through the Treaty of Versailles by the end of World War I and was part of a process to subject China to other countries. The intense mobilization became known as May Fourth Movement, and the pressure made by the people was successful: China did not sign the treaty.

The movement had a strong anti-imperialist and anti-feudal component, and it was forged within the so-called New Culture movement. Young intellectuals promoted ideas in defense of democracy and science through the New Youth magazine, launched in 1915, where they provided a critique of Confucian traditions and advocated for modernizing China, including with the use of vernacular Chinese in new literary experiments published in the magazine.

“Women’s issues”—or “women’s problem” according to the Chinese expression—was one of the topics discussed in the period, both through feminist writings translated and published in the magazine and writings by the movement’s intellectuals. One of the principles of the Confucian social order was the hierarchy of the husband over the wife—a gendered hierarchy. Most authors organizing this critique were men, and they pinpointed women’s oppression and patriarchy at the base of Confucianism. Understanding women as human beings, with independent personhood, was at the center of these conversations, and legitimately recognized women as actors in the public sphere.

Women’s emancipation therefore appeared as a condition for a modern China, along with nationalism and new democratic values driven by the anti-imperialist movement.

Before the May Fourth Movement, major changes had been happening in China and Chinese women’s lives. One example is that the practice of binding women’s feet was outlawed, though with more effective outcomes in some places and among some social groups than others. But many extreme forms of violence of patriarchal relationships that were fundamental for the semi-feudal order of the time lived on and would only be overcome with the 1949 revolution.

After decades known as the “century of humiliation” starting with the Opium War (1840) and the occupation of Chinese territories and institutions by foreign powers (like England, France, and Germany), the May Fourth Movement is, to this day, understood as an anti-imperialist awakening among the Chinese people.

The mobilizations spearheaded by young intellectuals were followed by grassroots uprisings across different parts of China, like Shanghai and more than 100 towns in 20 provinces. The uprisings included strikes—and that was also when the emerging working class became a major actor in the political scene. After the events of May 4th, women’s political participation also started to expand.

The possibilities opened up by the Russian Revolution two years prior influenced that context, with the growing affirmation of Marxism and Socialism. It was not only about translating ideas, but about an intense process of political organizing and formulation, a benchmark of which is the establishment of the Chinese Communist Party in 1921.

There are different interpretations about the meanings of the May Fourth Movement for feminism in China. On the one hand, the movement acknowledged women’s oppression and forged new terms and new subjectivities related to the “new woman” category. On the other, this was somewhat restricted to a social group of intellectual and urban women. Nevertheless, affirming equality between men and women became part of the agenda at the time.

The conditions to have this notion of equality reach all Chinese women were set out with the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, which was the outcome of a long struggle that relied on the strength of working and peasant women.