Doing grassroots communications is a collective process. It is more than just taking a picture, posting a video on social media, writing a news story—it is a way of building a movement. Those who make it happen are never alone, because they work with other communicators and because they are connected to a process of political organization, a process of a shared struggle.

Especially in Latin America and the Caribbean, the power of grassroots communications has led to historical processes that have built important spaces of convergence. The brochure We Are All Communicators [Somos todas comunicadoras], produced by the World March of Women Brazil, explains the movement toward the dynamics of convergence.

Convergence is activated through a joint effort between alternative media and social movements, which provide their own communicators to take part in the collective process. Planning and production of content happen together: communicators from different organizations can establish a radio team, share photos, write news stories, and work collective on social media. The materials produced through convergence express the political synthesis of each specific political process, and they must express the political positioning and representation of organizations. It is a moment of collective production and learning.

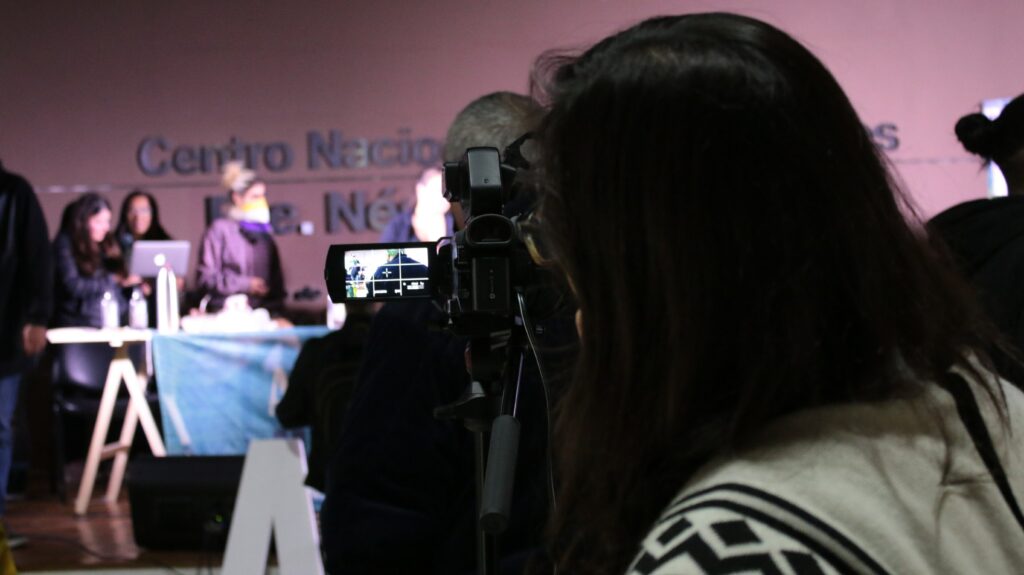

Practicing convergences in communications is a continuous endeavor, through joint efforts and forums with media outlets and movements. And it is especially important during collaborative coverages of demonstrations, activities, actions, meetings. In these spaces, while holding a camera in one hand and a flag in the other, communicators share materials, practice unity, propose different languages, which, when combined, create common content, always from the perspective of those who are part of the struggle.

During the 3rd Continental Assembly of ALBA Movements, which took place between April 27th and May 1st, 2022, Capire collected stories from sisters tasked with communications during the meeting.

The Battle of Communications

María Aprigliano, of the Latin American Information Agency [Agência Latino-americana de Informação—ALAI], explained that “what we are doing is especially trying to cover not only the people who take part in the panels, but also the experiences that our comrades bring in.” “ALAI is a process of grassroots communications that has, since the 1970s, developed and become richer along with processes of social movements in the continent,” explained Sally Burch, a co-founder of the agency, adding that communications is “a work connecting movements.”

Grassroots communications plays a role informing both people who are active militants and those who may eventually become militants as well, who are not part of the “reformed” group yet. According to María, “we try to replicate information on different digital platforms to provide more exposure to this massive experience, which must reach the great majority of grassroots movements.” Meanwhile, doing communications also means challenging the way big digital conglomerates distribute content and pushing democratization of communications and technologies on the agenda of movements. “We are tasked with warning movements about the new dangers that are emerging, and one of them today is digital capitalism, with new companies that we carry every day in our pockets, our phones, and even on our beds. What strategies we can think of in face of these challenges is a question we can pose to each other within ALBA,” Sally argued.

Big transnational social media corporations promote themselves as spaces of open debate, but they continuously practice censorship and manipulation of information, while also strengthening consumerism and neoliberal ideals based on individualism and meritocracy. On the panel about the role of youths, Venezuelan-born Orlenys Ortiz pointed out that these companies work to “annihilate anything that opposes the interests of the US, annihilate the leadership of Commander Chávez from collective imagination.” She added that “this is part of a territory under dispute. We are called to wage this struggle both in the territories, in their deepest aspects, and in international meetings such as this one, as well as wage the digital battle from our position.”

Collective Processes

During the assessment panel of the operational secretariat of ALBA, Laura Capote spoke about the integration between communications, political education, and politics. These three pillars must be understood and combined in practice, with no fragmentation. This concept is part of a way of organizing that works under “the principle of humbleness and collaboration between us.” And she added: “All of those things that are seen—that is, potential setbacks, electricity issues, etc.—are part of a movement that has to get moving while also dealing with grassroots community kitchens, the criminalization of comrades, and multiple organizational tasks. This is done by militants of the people from each of these countries. It is not that we are organizers and you are guests here—we are all organizers.” Sally said this integration is also part of everyday practices in spaces of communications in movement: “we have been following processes that are not only providing information, but also political education.”

Luciana Lavila, of Barricada TV, looked back at experiences as part of the history of the building of grassroots communications in Latin America and the Caribbean. “There have been great grassroots communications and journalism schools. Cuba and Venezuela are big examples, as well as the radio stations of mining workers in Bolivia… There is this entire tradition of struggle that marks all of us who do grassroots communications. Here in Argentina, since 2001, there is an entire tradition of picket-line cinema, of grassroots organizations and movements becoming more aware of how important communications is.” Barricada TV is actually an example of that: it is a grassroots and community-based TV channel based in Buenos Aires, Argentina, broadcast via digital television (32.1) and internet. Barricada TV first started with experimental broadcasting in neighborhoods, along with movements of unemployed workers, after the Argentinazo, as the 2001 crisis was dubbed in the country. Over the years, the collective decided to expand its audience and build a structure for the TV channel at IMPA, a restored metal factory.

For Luciana, this awareness is fundamental and it “goes beyond the matter of communications tools.” “If we don’t understand that comrades must be integrated in the struggle, because we are militants, as well as communicators, things get more complicated,” she argues.” The same is true for positioning the right to communications as a general political agenda: “Just like social movements take to the streets to express their demands, the communications sector and these organizations must fight against the concentration of the word.” Orlenys Ortiz criticized “the fact that communications is not understood as a cross-sectional pillar across absolutely everything. Communicators are often the only ones talking about communications, and that cannot happen anymore.”

Women communicators have been building new accumulated knowledge about feminism and grassroots communications, making women’s contributions and resistance more visible and proposing anti-patriarchal views and language. “The experience we are having here is very promising and beneficial, because there are many sisters who are working with feminist pillars. This gives us the possibility of joining forces from now on to plan strategic pillars that require us women to spearhead them,” María Aprigliano said.

To be a grassroots communicator, the most important thing is to actively take part in the struggles, because it is through them that you will learn to formulate communications desde abajo—from the bottom. “While learning to multitask in the corporate world is really bad, it is true that we, grassroots communicators, learn how to do a lot with few tools. This is possible because we are in this environment of struggle, because there is no point in doing it just for the sake of it, otherwise it loses its magic,” Luciana explained. Social communicator Zaira Arias, of the Free Peru [Perú Libre] party, said, “New communicators must be born, ones who are not necessarily journalists, but people who want to communicate the truth and wage a direct battle against lies, against the right that relies on all the logistics in the world. We do not have that, but we have the truth on our side.”