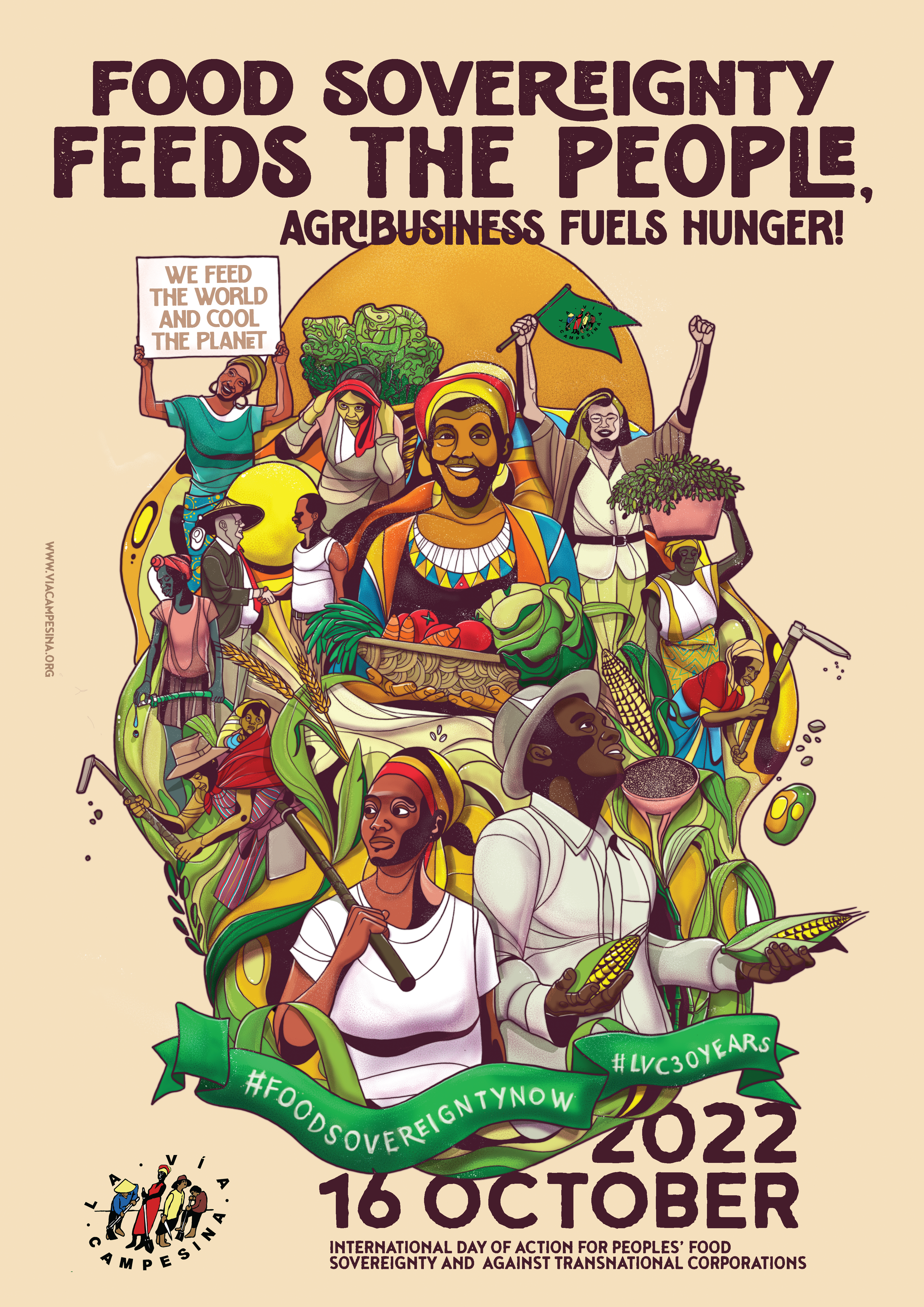

October 16th is International Day of Action for Peoples’ Food Sovereignty and Against Transnational Corporations. The Food Sovereignty principle, proposed by La Via Campesina (LVC) in 1996, defends the peoples’ right to define and conduct the production and consumption of healthy foods. This is a feminist principle, as women around the world are primarily in charge of food production and preparation, whether for subsistence or trade. This accumulated experience provides women with different kinds of wisdom and knowledge, which account for protection, cultivation, and storage of seeds and biodiversity.

Protecting, expanding, and exchanging these ancestral forms of agroecological knowledge between communities, forged in everyday struggle, is one of the main strategies to build food sovereignty. Peasant grassroots education provides new perspectives for working on the land and creates alternative training methodologies. An agroecology school project was created by La Via Campesina through international joint efforts during the 2005 World Social Forum in Porto Alegre, Brazil. At first these schools were planned to be implemented in Brazil and Venezuela, but they later spread to other countries across five continents where the LVC works, and they represent experiences of change in peasant territories. This year, 2022, marks 30 years of struggle and resistance of La Via Campesina for the rights of peasants around the world.

Experiences of Agroecology Training

One of Latin America’s most long-established agroecology processes is the Latin American Agroecology School (Escola Latino-Americana de Agroecologia—ELAA), located in an important territory for the battle for grassroots agrarian reform in Brazil, the Contestado settlement in Lapa, Paraná state. Established in August 2005, it is the result of the collective and continuous building efforts of La Via Campesina and Brazilian organizations that are part of it, including the Landless Workers’ Movement (Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra—MST).

Amandha Silva, an MST militant and resident of the Contestado settlement, pursued a teaching degree at the ELAA in Countryside Education—Natural Sciences with emphasis in Agroeology. Now Amandha is part of the school’s political board. Speaking with Capire, she talked about the ELAA’s history, as an important space to promote agroecology at an international level. More than 30,000 people coming from social movements, universities, international organizations, schools, unions, and political movements have visited the school during exchange programs, seminars, courses, workshops, etc. Their educational practices are based on dialectical and historical materialism and grassroots education, and they are fostered by a humanizing perspective of humane education. One of the school’s goals is to strengthen agroecology as science, practice, and movement. “Understanding agroecology in its human, social, economic, and political dimensions, one of ELAA’s major tasks is to educate, organize, produce, socialize, and build, through education and agroecology, processes that aim to change the current societal model,” Amandha says.

Agroecology challenges the capital model, it is the struggle for acknowledging the peoples and their knowledge, it affirms how urgent and necessary it is to forge new relationships between human beings and with nature.

Amandha Silva

There are many experiences of change through education around the world. The Network of Small-Scale Farmers’ Groups in Tanzania (Mtandao wa Vikundi vya Wakulima Tanzania—MVIWATA) is the country’s largest small-scale farmers’ organizations, with members both from continental Tanzania and Zanzibar. Before the Green Revolution wave, farmers in many rural areas of Tanzania practiced agricultural methods in harmony with their cultures, socio-economic conditions, and environment, through which they were able to feed their societies and the nation at large. Following the wake of industrial agriculture, the MVIWATA embarked on an education-based strategy to strengthen agroecological practices among farmers in areas where their practices were kept intact, as well as to transit farmers to more equal and healthier food production practices in areas attacked by the Green-Revolution wash, and to politically redefine and promote a dialogue on food systems and the agrarian question.

Theodora Emillian, a MVIWATA militant, is one of the training coordinators of the organization. She argues that understanding the local and global context of rural work is a necessary step

“to take forward the struggle for farmer-managed seeds and protection of biodiversity and the environment.” Their education experiences have allowed farmers’ groups and networks to produce and store their own seeds. “We have farmers’ groups and networks that set village demonstration plots for learning and exchanging skills and knowledge. It is powerful for many groups and networks acting to change the existing narrative pushed by capital,” Theodora says. Collective reflection and participation are key for the educational processes: “It has been agreed that everyone has to contribute in learning, making analysis, relating situations, and forging solutions, from which farmer-to-farmer learning also takes place.”

In the United Kingdom, rural youth organizations develop training programs to discuss issues that are relevant for new militants. One of these organizations is Youth, Food, Land, Agriculture: a Movement for Equality(Youth FLAME), a youth joint effort by the union Landworkers’ Alliance, which brings together farmers, producers, foresters, and rural workers from the United Kingdom. We talked with Hattie Hammans, a member of the Youth FLAME and the youth platform of the European Coordination of La Via Campesina (ECVC). Hattie told us that, like many young people, she joined the organization because she is concerned about the future of the environment and nature.

“We found that many of us are experiencing very harsh conditions, including no or limited payment and inadequate housing, food, and support. Of course, failing to support the next generation of agroecological landworkers limits the possibilities for socially and ecologically just food system transformations. That is why agroecology is an exciting idea for young people, as it brings together social and environmental justice, and seems to hold the solution to many of the unfolding crises that loom heavy over our futures,” she explains.

Agroecology and Feminism

The struggles for agroecology, food sovereignty, and feminism are inseparable. Popular peasant feminism not only works to advocate for land, the peoples, and nature, but it is also fertile ground for women to discuss, talk about, and analyze their living conditions, as well as formulate the critique and ways to tackle the forms of violence they are subjected to, as well as to fight conservatism in the countryside. In these spaces, women learn with and empower each other in the struggle for emancipation.

Theodora Emilian says that, in one of the training programs of the MVIWATA, participants were asked about what feminism means to them. Together, they reached the conclusion that feminism is also about fighting for agroecology. “It’s the struggle for women to own land and cultivate it with what they want, using their own seeds and skills with no external inputs,” Theodora explains. She argues that the organizations’ experiences demonstrate that agroecology is able to feed people with safe food and give farmers autonomy and security of their lands, seeds, practices, and rights. For women, that means securing a decent life for themselves and their families and communities. It means securing life and work that are driven by autonomy and camaraderie, reducing hierarchies with husbands and other men in the communities.

It is also based on grassroots education in the countryside and their critical perspectives that women realize that the personal is political. Upon this reflection, the centrality of feminism and women’s struggles become clear as being key elements for the processes of struggle in mixed-gender social movements. “We believe in education for emancipation, one that builds educational processes of awareness raising by empowering and humanizing,” Amandha Silva argues, adding that “popular peasant feminism emerges from the territories where the conversation meets the struggle, where oppression echoes for liberation. It is a political tool to fight an everyday struggle, of resistance, which aims to emancipate peasant women. And it is not limited to liberating peasant women in the sense of their individual demands, but rather their collective ones.”