In the Spanish state, people do not have access to decent housing. Wages are neither on par with nor proportional to housing prices. In 2008, due to the housing crisis—the so-called “housing market bubble”—, housing prices increased both for renting and buying, while wages did not. Today’s reality is that renting a home for a family costs three quarters of a wage. If someone earns 1,100 euros, the so-called minimum wage, they will often spend 900 euros on rent. Families need two sources of income to support their everyday lives or face very complicated situations. The housing crisis is also related to the lack of job opportunities.

People today cannot even imagine if one day they will be able to buy a house. It’s a very different reality from that of past generations, where there was the possibility, thanks to better working conditions, to climb the social ladder and buy a house. To be able to rent a house—as this is the reality for the majority of the population—, you need a job contract that is not temporary, as well many unattainable requirements. For many people, especially migrants, it is impossible to find a place to rent, so they are offered completely offensive and outrageous things. One example is a sister from Bogota, who has been offered a room for 250 euros, which she could only use on Sundays. It was a room offered to women who do elder or child care work for other people and only have Sundays off to rest.

I believe this is a global crisis, which is due to neoliberalism. It is not even the reality of reformist capitalists from the early 20th century, which allowed for certain conveniences and social aids to prevent the people from revolting—that is, to prevent protests. In Catalonia, there are 350,000 empty houses. This is speculation: owners wait for the demand to increase, and, due to the lack of offer generated by themselves, they can raise housing prices.

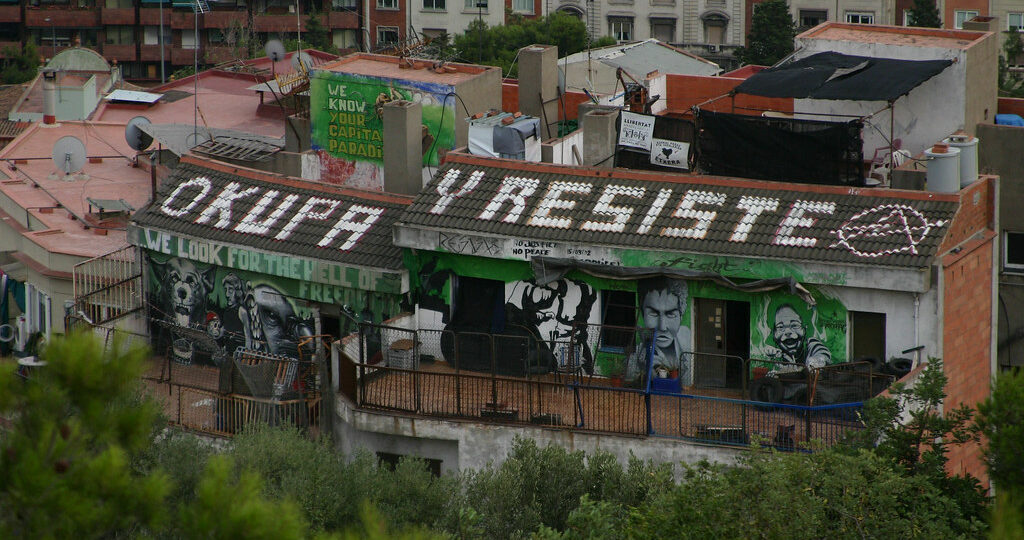

During a webinar held by the World March of Women in 2023 about the housing crisis around the world, some sisters spoke about the complex experiences in housing cooperatives that are in the hands of the state—that is, which rely on state intervention. In the Catalonia Okupa movement, we are very connected to libertarian thought. We believe in the okupation, we believe that okupying spaces allows us to live collectively, and this collectivity allows us to work on values that got lost in the family structure. Doing this in Europe, however, is not the same as okupying and resisting in South America and other parts of the world.

Struggle Experiences

In Manresa, a city in Catalonia near Barcelona, there is a very powerful organization called Platform for People Affected by Mortgages [Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca—PAH], which became well-known due to the political work done by its spokesperson Ada Colau, which was later elected mayor of Barcelona, holding office between 2015 and 2023. Currently in Manresa, there are nine buildings occupied, which have been recently built and are owned by high-risk investment funds (the so-called “vulture funds”), like Blackstone. Through their occupation, these properties are being offered primarily to migrant families, usually from North Africa. The PAH is part of a network of grassroots structures that cover other needs that should be the responsibility of the state. Grassroots organizing is what allows certain needs to be met.

There are also important experiences from northern Europe, where housing cooperatives have existed since the 1940s-50s, when migrants came from southern Europe. After World War II, the government of Sweden demanded workers for cheap labor. In the housing cooperatives built by these workers, a person does not own their apartment, but a percentage of it. Decisions are made collectively, yet everyone lives in their own home. Securing decent housing for everyone is necessary, everywhere.

Women’s Participation

When the PAH started its work, especially women and migrants took to the streets. When they heard about an eviction taking place, migrant women would stand up for these houses and tenant families. They would gather outside the homes from where families were being evicted to stop the police from coming in. It should be noted that the terms “eviction” and “displacement” are different—the former happens when someone was a tenant, paid rent for a while, but can’t afford it anymore—occupations (with the double “C”) take place here to fight evictions—; meanwhile, the latter is what happens with the okupations with a “K.” Both are extremely violent situations.

Under Mayor Ada Colau’s administration, mediation efforts were made with the city government, for example, to try to cover rent prices to prevent families from being removed from their homes the same day. These are families with small children and no alternatives. The administration and social services only provided lodging for two weeks for families with children. All women bear great responsibility, because they are the caretakers of their families. Very often they are alone with their children and, if they live under unstable situations, with no housing or income, the state can take their children away. It is a constant danger.

In face of this situation, the collective Soror, for example, offers support to migrant women, helping them to learn Spanish and providing a safe space where they can share their experiences. Many women have chosen not to occupy, not because of their political ideology, but out of necessity. A young 25-year-old sister who is the mother of a baby once said, “I don’t sleep. I don’t sleep at night. I can’t sleep.” She was afraid that the Directorate General for Child and Adolescent Care [Dirección General de Atención a la Infancia y Adolescencia—DGAIA] would take her daughter from her. When a woman is homeless, they take their children from her. But if she doesn’t have a job, she cannot pay rent; if she doesn’t have papers, she cannot get a job. It’s a downward spiral of precariousness and vulnerability in which women suffer more than men, because they are responsible for their community and for everyone’s care.

I am translating a book about capitalism in the early 20th century called The Capital Order, How Economists Invented Austerity and Paved the Way to Fascism, by an Italian-American author, Clara E. Mattei. According to this book, in Great Britain, after World War I, there were three years of workers’ struggle, and social rights were achieved—some allowed by reformists who wished to appease the working classes. The interesting thing about this is that a Housing Committee was created and, concurrently, the Women’s Housing Subcommittee. Women aimed to create common spaces, outdoor meeting places. For two years this project was designed under women’s guidance and decision-making. Unfortunately it was not implemented, as austerity came to Great Britain, concurrently with fascism rising in Italy.

They advocated for the creation of community laundry facilities, community kitchens, neighborhood organizing, gardens, large windows, good air circulation. Women take care of our well-being.

In our work, following a more anarchist and libertarian thought, it is not up to us to have any expectations about the state. Along these lines, we aim at true self-management, or at least a genuine, concrete attempt at self-management. This means taking spaces without asking anyone’s permission. And in these spaces, it means to dream with a fairer world, outspokenly, with other sisters.

Isadora Prieto lives in Catalonia, is an interpreter and a member of the World March of Women in the Spanish state.