In Quebec, the feminist militant Marielle Bouchard took on the challenge of cycling 1,000 kilometres to protest femicides. The ambitious aspect of her endeavour was time: to finish it as fast as possible—and to Marielle, that meant three days.

While she started the project with the desire to rise to a personal ultracycling challenge, it was the power of conviction that made her go all the way. “I was very motivated, I would not give up for lack of motivation.”

The idea first emerged in December last year, seven months before the ride. She had ridden 500 kilometres the previous summer and experienced pain for a long time after the ultracycling experience. And as she planned to double that distance, she could not do it for no reason. “It had to mean something.”

Deciding to Bike Against Femicides

For context, Marielle uses her bike in her everyday life, but she also works and carries out activist work dedicated to unemployed women’s rights—that is, a struggle for fighting women’s poverty. During the health crisis, she noticed a new disturbing phenomenon. On more than one occasion, women told her they feared for her lives, even when that was not the topic of the conversation. They would say, “I really thought I’d be next.”

The next femicide victim—that was what it was about. In recent years, the number of femicides increased significantly in Quebec as well as in other parts of the world. One in six couples lives in a violent context in Quebec. For every femicide, more than 16,000 women experience a harmful home environment.

Violence and femicide should be addressed—that was the starting point. Marielle wanted to expand the conversation and go beyond the realm of couples, also talking about other often hidden aspects of it. So she decided to raise funds for the House of Marthe [Maison de Marthe], a community organization that helps women who want to leave a situation of prostitution-related sexual exploitation. In the words of a woman who attends the centre,

The House of Marthe is a beam of light in my life. It shows it will be there for my moments of madness and despair and shows me I am not the only one who got lost along the way. Other women like me have been trampled on, and together we are all learning how to get up.

Cynthia Dionne, survivor

The fund-raising campaign encouraged her to accomplish the double goal of riding 1,000 kilometres: her personal goal to outdo herself and the collective goal of promoting a conversation about femicide.

How Far?

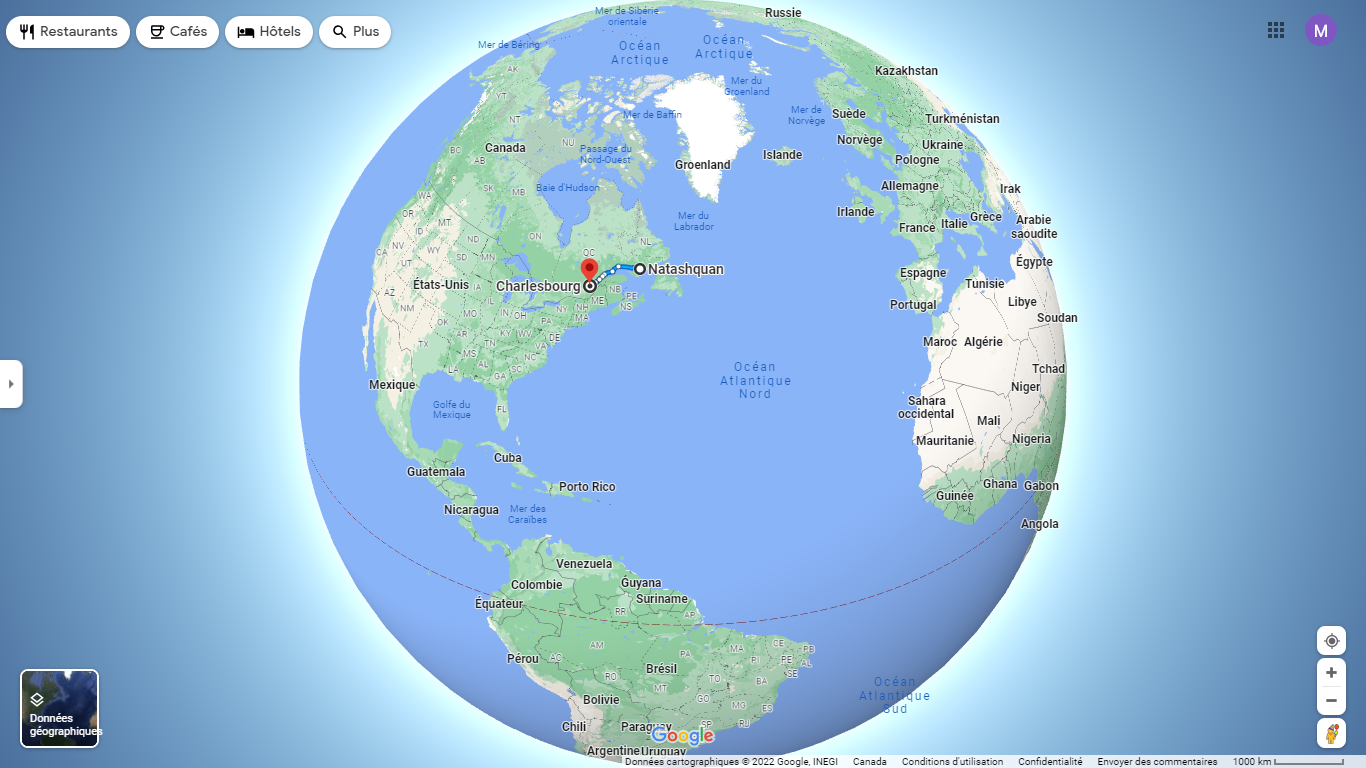

From Quebec City, Marielle was planning to ride 1,000 kilometres to Natashquan across the north noast of Canada. This route inspires the imagination for the great coastlines along the road, but it is especially relevant because the north coast has a significantly larger rate of domestic violence cases than other parts of Quebec. Moreover, she would ride through several Indigenous communities along the way.

Indigenous women are overrepresented among femicide victims, nevertheless little is said about them. In Canada, while they only make up 4 percent of the population, they represent one fourth of women who are killed. Quebec is no exception compared to other parts of the world where colonialism and racism maintain unequal social relationships. The communities still bear the intergenerational consequences of the Indian residential school system,[1] while decision makers hesitate to use the words “cultural genocide” to describe the violence and abuse perpetrated against these communities. Marielle wanted to listen to what the people along the way had to say about it.

Departure Day

After months of preparation, on Wednesday, 27 July 2022, at 5:15 a.m., friends, sisters, and women’s groups came together to encourage Marielle, but also discuss the situation of femicides in Quebec. Statements were made sparking uproar and outrage. Emotions were mixed with gratitude and admiration for Marielle, whom they wished a good ride, chanting “Not one more [death]” [Pas une de plus!].

We were somehow concerned, but most of all, we trusted her skill and conviction. And she did not lack conviction. Meetings were organized along the way to motivate her on two levels: encouragement and outrage. The meetings prompted by her ride enabled exchanges about femicide, an incredible media coverage, meetings with grief-stricken people, sharing of unfair stories, moving accounts. The collective reasons proliferated along the way to motivate her to keep going.

One Turn of the Pedals at a Time, One Kilometre at a Time

Marielle was well prepared, but hills, heat, knee pain, and dehydration also crossed her way. In the second evening, she and her technical team had to make the decision to wait more than ten hours for the wind speed to decrease from its 50-km/h gusts, because with heavy rain at night, her safety was at stake. This decision meant the challenge would be concluded by the fourth day, and not before the end of the third day, as she intended. That was the toughest moment for her, but she never doubted she would go all the way.

Marielle managed every turn of the pedal to keep the right intensity to arrive safely without getting hurt. She was also alert to her body’s response and need to hydrate, eat, protect from the sun, and do it all over again and again. Her technical teams were there to remind her of these essential elements and make sure she was safe. After all, we never do anything completely by ourselves.

In fact, people who knew about the challenge and her cause encouraged her on her way. Feminist groups and members of the national coordinating body of the World March of Women in Quebec called for the mobilization. The meetings resulting from these mobilizations included the ones in the Pessamit community, where Marielle had inspiring exchanges with Kathy Picard, of the Innu Council of the Pessamit Reserve [Conseil des Innus de Pessamit]. Kathy said she wishes that “the future generations [of Indigenous women] are seen as human beings by everyone.” She also offered Marielle a red dress as a symbol of the struggles waged by Indigenous women and their allies to demand investigations into missing Indigenous women and girls. Kathy Picard assigned Marielle the task of taking the red dress all the way to the finish line.

Achieved Goals

Marielle successfully rode 1,000 kilometres in 66 hours and 22 minutes. Quite an achievement! The other successful story is that, at the social level, people talked about it in the three areas she rode through, and she reached the media at a national level. The admiration for Marielle’s feat forced the media to talk about the topic that encouraged her.

More than one media outlet mentioned the very interesting parallels to be drawn with women who are stuck in violent situations. We see, for example, the link with this road full of traps that is similar to what women have to face. This is what they said in the first meeting, “Women have to face Olympic-like trials to flee violence and, unfortunately, some of them do not make it.” Violent situations require continuous caution to stay safe.

The interview that resulted in this article was granted ten days after she finished her 1,000-km bike ride, and Marielle has not fully recovered yet. She is tired and really needed to hydrate and eat for 24-48 hours after achieving her goal. The body can endure so much, but it also needs time to recover. Once the uncomfortable situation is over, things don’t just end—one has do adapt and find a balance.

Not One More!

A conversation started thanks to this challenge—but now it must continue. One of the messages Marielle stressed during her journey is that a case of femicide is never really a surprise, but rather it is the ultimate consequence of a process in which we should have socially gotten involved. Preventive action must be taken to prevent yet another victim. Every time there is a femicide, it requires us to question our structures.

Nevertheless, the experience is there—just listen to the women’s groups that have been deep-rooted in communities for more than 50 years. These organizations, which struggle and receive women’s support, have concrete proposals. They should be offered resources and their critiques should be listened to to really build trust.

After Marielle’s journey, we heard about a new femicide victim, Audrey-Sabrina Gratton. This is not just a number—it is a person, with likes, interests, habits, friends, family… It is a void caused by a system that has not yet been able to stop the violence against women. Against all women.

We will keep marching until all women are free!

[1] Network of boarding schools for Indigenous children that operated a system of assimilation and genocide in Canada. Attendance was mandatory until 1947, but the Canadian state continued to take Indigenous children from their families until 1970s. It was only in 2008 that the Canadian government issued a formal apology for this state policy that affected more than 150,000 Indigenous children over more than 100 years.

____

Marie-Hélène Fortier is a member of the Coordinating Body of the World March of Women Quebec. With information from the website Le Soleil.