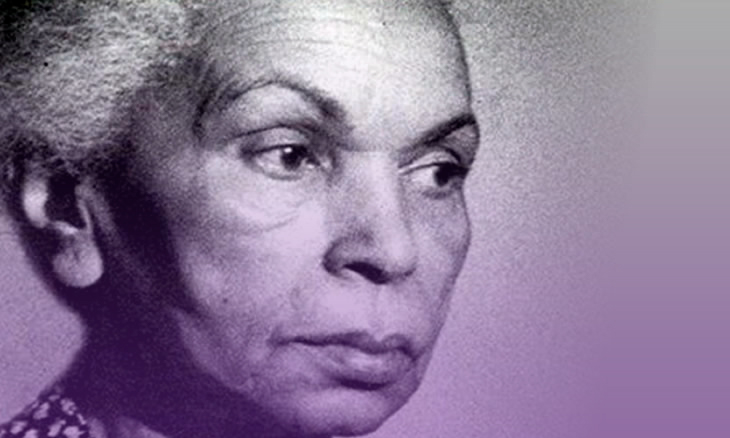

Noémia de Sousa was one of the most influential Mozambican poets of the 20th century. Her poems are found in the book Sangue Negro [Black Blood], published for the first time in 2001, months before her death. However, it was between 1949 and 1952 that she wrote most of her poems, when she was in her twenties. The researcher Laura Cavalcanti Padilha says that “for 50 years, mimeographed copies of her work circulated from hand to hand, often very precarious copies.”

It is amazing to think that we have read Sangue Negro all this time, working on it in essays, books, courses, etc. […] Thesis and dissertations have been written about a work that remained unedited, which seems absolutely astounding. […] The book took shape, with soul and voice, a year before its author died, in 2002. I think this is a symbolic fact and a symptom, and you cannot consider it only through the historic series of chances and coincidences.

Laura Cavalcanti Padilha, 2004

Noémia de Sousa was a collaborator at O Brado Africano [The African Cry], a Mozambican publication that fostered literary productions and formulations about Africanity. Her production, marked by a politically engaged and collective voice, played an important role to empower anti-colonial expressions in Africa. The poet and researcher Bianca Gonçalves argues that “building a Black identity, pursuing Africanity, and acclaiming freedom are common topics in her poetry, as required of the generation of poets before the independence.” The literature produced by Noémia and others of her generation played a key role in building an anti-colonial sentiment and also in establishing a poetry that could be free from the exclusive parameters produced by European culture.

And suddenly I decided to write this thing because I saw things that were featured in newspapers there and I thought people were always writing about Portugal. People would write, they would always write as if they were in Portugal, and I, a confluence of I don’t know how many races—in my family alone I was in contact with nearly all ethnic groups that were there and, therefore, followed a bit of the lives of everyone—, and I would feel outraged over the things that happened to me and to others all the time, and I thought people were turning their backs on reality.

Her poems were published in newspapers and magazines, outlets with wide circulation that were more easily accessed than books; this is why they would also pass a lot by word of mouth. “Noémia de Sousa resisted the book format because of the levels of illiteracy among her people, thus reiterating the place of the poetic word in the circles of orality,” Bianca explains in her review of Sangue Negro.

Black people had no access to these schools, to public education! Black people only had access when they became assimilated. When I studied, it was a very big school, and it did not have one Black student. […] Black people had to assimilate and have documents provided by authorities claiming they lived like whites: that they ate at a table, not on the floor or a mat; that they slept on a bed, etc.; that they spoke Portuguese—that is: that they had assimilated into Portuguese culture.

While the poet praised anti-colonial and grassroots African and national culture, her work also placed Blackness from an international viewpoint, stating the mutual support and kinship between Black peoples of the world, as well as paying tribute or referencing Black figures of the arts and politics from the Americas. The poem we share below to celebrate Noémia on her birthday is about that. In “Let My People Go,” Noémia de Sousa uses music to bring the night in Mozambique closer to the night in Harlem, a Black neighborhood in the United States; she brings the marimba closer to the blues, and unites the different forms of resistance of subaltern Black peoples against the same colonial process.

Let My People Go

for João Silva

Warm night in Mozambique

and distant sounds of marimbas reach me

– sure and constant –

coming from where I don’t know.

In my house made of wood and zinc,

I turn on the radio and let myself be lulled…

But voices from America agitate my soul and nerves.

And Robeson and Maria sing to me

Negro spirituals from Harlem.

“Let my people go”

-oh deixa passar o meu povo,

let my people go! –

they say.

And I open my eyes and I cannot sleep.

Anderson and Paul resonate inside me,

not sweet voices of lullaby though.

“Let my people go”!

Nervously,

I sit by my desk and I write…

Inside me,

deixa passar o meu povo,

“oh let my people go…”

And I am no more than an instrument

of my blood that is stirred

with Marian helping me

with her deep voice – my sister!

I write…

By my desk, familiar figures come lean in.

My Mother of rough hands and worn-out face

and revolts, sorrows, humiliations,

tattooing black the unblemished white paper.

And Paulo, whom I don’t know

but who has the same blood and the same beloved sap of Mozambique,

and miseries, fenced windows, the good-byes of magaíças,*

cotton fields, my unforgettable white companion

and Zé – my brother – and Saúl,

and you, a Friend of sweet eyes of blue,

taking my hand and forcing me to write

with the acrimony from my outrage.

They all come and lean over my shoulder,

as I write into the night,

with Marian and Robeson watching through the radio’s glowing eye

“let my people go,

oh let my people go!”

And as long as voices of sorrow

come to me from Harlem

and my familiar figures visit me

in long sleepless nights,

I cannot let myself be lulled by the futile tunes

of Strauss’s waltzes.

I shall write, I shall write,

with Robeson and Marian shouting with me:

Let my people go,

OH DEIXA PASSAR O MEU POVO!

(*) Mozambican workers who migrated to work in gold mines in South Africa.