On a cold winter morning in Bitola, a thin layer of black dust covers the window sills before dawn. It comes from the nearby coal-fired power plant, the largest in North Macedonia and one of the biggest air polluters in the Western Balkans. For the women who live here, cleaning that dust has become as routine as boiling water for coffee. What is invisible, however, is the way this pollution shapes their daily lives — their health, their work, their time, and their futures.

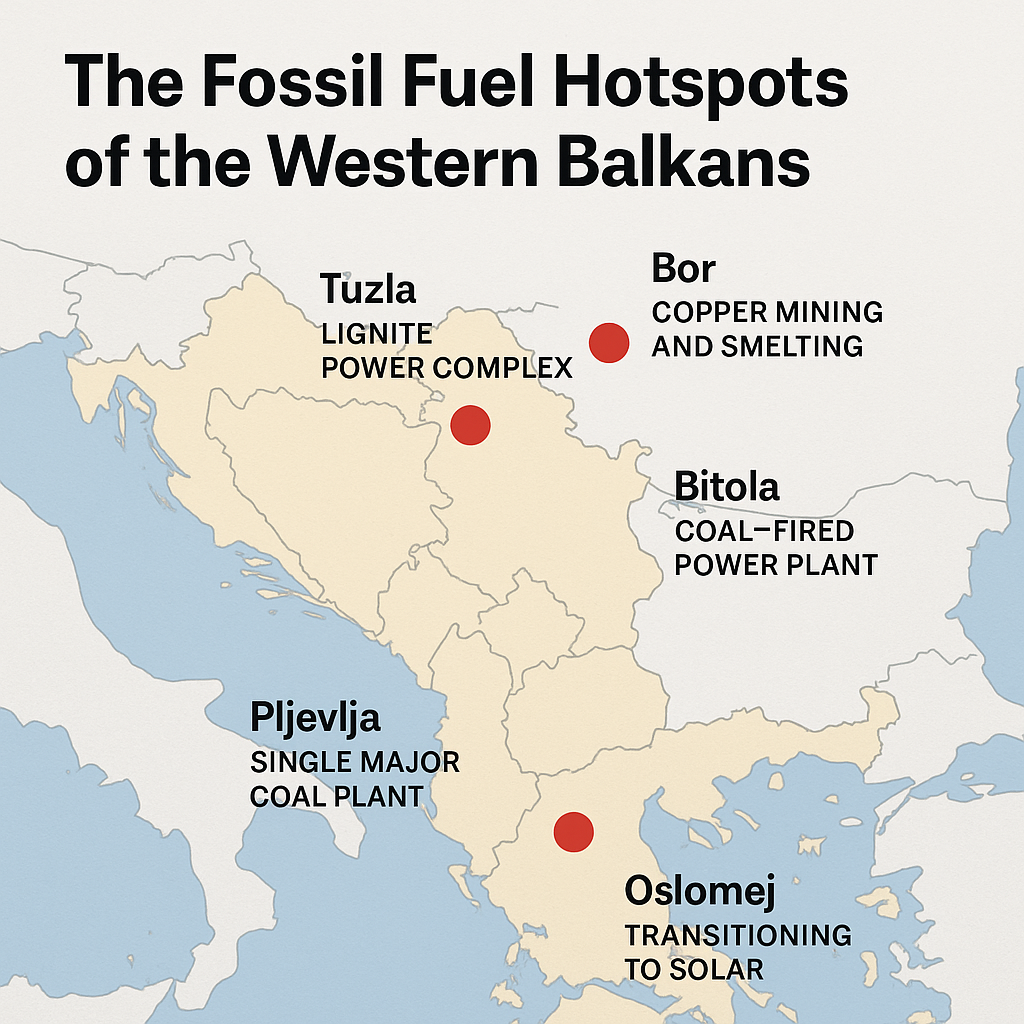

Across the Western Balkans — from Serbia’s copper mines to Bosnia’s lignite valleys and North Macedonia’s thermal plants — the story is the same: the economy still depends on fossil fuels, and women quietly carry the heaviest burdens of that dependence. While energy debates focus on kilowatts and investments, few asks who pays the human cost.

According to the European Environment Agency, six of Europe’s ten dirtiest power plants are located in the Western Balkans, emitting more sulfur dioxide than all European Union (EU) coal plants combined. In North Macedonia, around 45% of electricity still comes from coal, while in Serbia the figure exceeds 65%.

A Gendered Crisis

Air pollution in the Balkans is among the worst in Europe. According to the Health and Environment Alliance (HEAL), coal plants in the region cause tens of thousands of premature deaths every year. In North Macedonia alone, air pollution kills more people per capita than in any EU country. Yet behind these statistics are individual stories — of mothers caring for sick children, of women who cannot afford to heat their homes, of grandmothers living near toxic ash ponds.

“Women in our region are on the front line of environmental degradation,” says environmental journalist and activist Aleksandra Nakova from Skopje. “They are the ones managing households, raising children, caring for the elderly, and at the same time breathing the dirtiest air in Europe.”

The HEAL estimate that pollution from Western Balkan coal plants causes 19,000 premature deaths and 8,500 cases of chronic bronchitis in adults every year across Europe. In Bitola alone, average PM2.5 levels in winter exceed 70 µg/m³, nearly seven times higher than the WHO safe limit.

From a gender perspective, the fossil fuel crisis is not only about emissions — it is about inequality. Women are more likely to experience poverty, to live in energy-inefficient housing, and to lack access to decision-making spaces where energy policy is defined. They are exposed to pollution through unpaid care work, and often excluded from the better-paid jobs in the energy sector.

The gender-just energy transition framework, now used by the UN and feminist organizations worldwide, helps unpack this imbalance. It asks three key questions: Who bears the costs of our energy system? Who has a say in shaping it? And whose needs are recognized? In the Western Balkans, the answers reveal a deep structural injustice.

Fossil fuel pollution is not gender-neutral. Studies link long-term exposure to particulate matter with higher rates of miscarriages, infertility, and breast cancer. In mining towns like Bor in Serbia or Tuzla in Bosnia, residents report rising numbers of respiratory diseases and cancers. But few of these health statistics are disaggregated by gender — making women’s suffering statistically invisible.

In Bitola, pediatricians have long warned about asthma among children. “Every winter, the hospital fills up,” says one local nurse who asked not to be named. “The air smells of burning coal, and mothers come in with kids struggling to breathe. It’s always the mothers — they stay home, they take time off work, they sit by hospital beds. Pollution steals their time and their strength.”

Health systems in the region rarely connect environmental pollution with women’s reproductive health or mental wellbeing. Most government reports treat air pollution as a technical issue, not a social one. The invisible connection between fossil fuels and gender inequality remains largely unexplored.

Energy Poverty and Everyday Survival

While politicians talk about energy transition, millions of Balkan households live in what experts call energy poverty — the inability to afford adequate heating, cooling, or electricity. According to the Energy Community Secretariat, nearly one in three households in the region struggles to pay energy bills. Women, particularly single mothers, pensioners, and those in rural areas, are the most affected.

In many villages, heating still depends on firewood or coal. Collecting, carrying, and managing that fuel is women’s work. In old apartment blocks, it is usually women who queue to pay the bills or argue with the utility company. When energy prices rise, women cut corners — they heat one room instead of three, cook less, or delay medical visits to save money.

In winter, poor air and poor heating combine into a vicious cycle: women inhale more smoke inside their homes, while men working in mines or plants are exposed outside. Yet the solutions — better insulation, clean stoves, solar panels — remain out of reach for low-income families.

The Male Energy System

The Western Balkans’ energy industries — coal mining, oil refining, power generation — are almost entirely male domains. Women represent less than 12% of the energy workforce in the Western Balkans, and fewer than 5% hold technical or managerial positions. In contrast, women perform over 70% of unpaid domestic work related to household energy — heating, cooking, and care.

In North Macedonia’s ongoing coal-to-solar project in Oslomej, hailed as a model for “just transition,” only a handful of women were involved in early consultations. Training programs for new green jobs in construction and maintenance still target men. Without deliberate gender measures, says Aleksandra Nakova, “we risk building the same patriarchy with solar panels.”

The transition from coal to clean energy is often framed as an economic necessity, but it is also a cultural one. For decades, male identity in Balkan industrial towns was tied to the mine, the power plant, or the factory. As those jobs disappear, social tensions rise — and women are left to absorb the shock, holding communities together through unpaid care, small farming, or informal work.

Voices Missing from the Table

Procedural injustice — the lack of women’s participation in decision-making — is one of the biggest blind spots in Balkan energy policy. In most countries, energy ministries, national utilities, and regulatory agencies are led by men. Consultations with affected communities, if they happen at all, are brief and technical. Local women — who might understand the daily consequences of pollution, price hikes, or blackouts — are rarely invited or heard.

Civil society organizations have tried to fill the gap. The Balkan WASH Network, for example, brings together women from rural areas to advocate for clean water and sanitation. Groups like Women Engage for a Common Future (WECF) and Journalists for Human Rights document stories of women living near mines and industrial zones. Yet their recommendations often end up as footnotes in official reports. “When governments talk about ‘energy transition,’ they imagine engineers and investors,” says Aleksandra. “They don’t imagine a woman hanging laundry covered in coal dust, or one deciding between paying for electricity or medicine. But those are the real human faces of energy policy.”

The Possibilities of Transition

A gender-just transition would mean more than replacing coal with solar panels. It would mean investing in people — especially women. That includes affordable childcare and public transport, so women can join new training programs; financial incentives for women-led energy cooperatives; and local renewable projects that benefit communities, not private investors.

Pilot initiatives already exist. In rural Serbia, a small cooperative run by women farmers installed solar dryers for fruits and herbs, cutting costs and creating extra income. In Bosnia, local women’s associations campaign for the right to monitor pollution data. In North Macedonia, women engineers are entering the growing sector of energy auditing and efficiency. These examples show that when women lead, sustainability becomes not only cleaner but fairer.

But such progress remains fragile. Without long-term policy support, many local projects survive only as donor-funded experiments. To turn them into systemic change, governments must collect gender-disaggregated data, set quotas for women’s participation, and link social policies — like care work and employment — with climate and energy goals.

Beyond Numbers: A Cultural Shift

The energy transition is not just technical; it’s deeply social. It requires rethinking what we value as “work” and who gets to shape the future. For generations, women in the Balkans have been described as victims of poverty or pollution, rarely as energy actors. Yet they are already energy managers — deciding when to turn on the heater, how to stretch fuel, how to keep a household alive through crisis.

Recognizing this everyday expertise is crucial. As the region moves toward EU membership and cleaner energy, gender equality must be built into every policy. The cost of ignoring it is high: transitions that exclude half the population are neither just nor sustainable.

The hidden price of power has been paid by women for too long. A truly just energy future will arrive only when they are no longer cleaning the dust of a system built on their silence.

Natasha Dokovska is a member of the World March of Women in North Macedonia.