The historical narrative around abolition is very much linked to the struggle against the plantation economy. As we know from Black, Marxist, materialist, radical feminists, the role of Black women was very crucial for the plantation economy in a way that more conventional conversations about reproductive labor cannot capture. Sexualized violence was a core principle of that system, and Black women were both working labor in the fields and forced to reproduce new slaves.

The history of the movement is much longer than just the question of the prison, the police, or the border. This was one of the first modern international movements, as the slave trade was a global phenomenon. So we see abolitionist projects in Haiti, in the quilombos1Quilombos are communities of resistance and refuge, originally created by Black people who were enslaved in colonial times in Brazil. Many communities are still alive today and the term is still used to refer to spaces of Black tradition, resistance, and social organizing. in Brazil, in Jamaica, or in the slave revolts in the United States and Canada. There are many examples of how people have engaged with social conflicts without reproducing the violence of the plantation system.

Because carceral violence impacts more and more parts of poor and racialized populations, it was historically always a part of Black and third-world radical feminism. That means that to struggle against his system as a whole, abolition is a two-fold project. It doesn’t simply mean the destruction of the system, but also the reconstruction or rebuilding of the life we want. It is about reinventing new relations.

Since the mid of the 20th century, the carceral state has become more and more unstoppable. That became the way the state deals with so-called social problems. So in the time of massive impoverization, we saw a withdrawal of the welfare state and a huge expansion of the carceral state. We see this in budgets and numbers. In the U.S., for instance, from 1990 to 2019, the female prison population has grown over 650%. It’s the largest growing population. In the United Kingdom, the female prison population has grown over 50%. In Nigeria, the women’s prison population grew by 70% in the last 20 years. So although we know that women or non-binary folks are not the first target when it comes to police violence, they are a growing target.

Many of the left liberal criminologists know by now that the research shows that prison doesn’t reduce harm. We have seen an increase of punishment in the last decades. And the problems we’re talking about have not decreased. This is an empirical argument of why we need alternatives. Tied to this is the political component which shows, based on the function of the police and prisons in a capitalist society, that the main goal is the criminalization of the poor and the securitization of the property order, always articulated to racial and gendered violence.

Knowing that this is the role for centuries, we know we cannot really get justice there. At the same time, the tough questions are: what are the alternative solutions?

Feminist approaches

There is a specific contribution that abolitionist feminists bring to this struggle in regard to the new carceral expansion. One was the intervention by Critical Resistance, who more than 20 years ago called a meeting with social justice movements to develop “strategies and analysis that address both state violence and interpersonal violence”. Racialized women and non-binary folks experience both. For instance, they sometimes defend themselves against racialized and domestic violence, and end up in prison as well. The majority of these Black, poor and racialized women in the U.S. are in prison because of poverty issues or because they fought back against sexual offenders. For these women, the state doesn’t mean protection, it actually attacks their communities. The plan was to struggle against state violence, and deal with the violence in our communities.

They called for a development of something else than the liberal, bourgeois feminist solutions that have an individualizing notion of violence. One is the method of community accountability, which deals with conflict or with interpersonal violence not just as an individual phenomenon. When something happens, the community is activated. It includes collective responsibility based on education to engage the community in questions around domestic and sexualized violence. It also includes restorative justice, a form of justice that is not focused on punishment, but on what the person who has to experience harm really needs, from healing to infrastructure or resources.

Another method is prevention and support. To do the prevention work, but also to rebuild the support structures such as infrastructural support, child care support, sociopsychological support, financial support. There are also non-carceral alternatives. People who have been doing violence, harm-doers, also need to be part of the process to be able to change their behavior. That’s tough work, but many women and non-binary folks who are severely criminalized know that it’s possible.

We often know that violence is a circle. That’s why, in abolition politics, we don’t merely talk of victims and perpetrators: because we know that most perpetrators have also been victims by violence domestic, state or structural violence. If we want to get at the root of violence, we have to develop methods to break that cycle.

Another method that is related to community accountability is the transformative justice, that targets the structures under which violence can occur, as the lack of health care and housing, poverty and criminalization. Transformative justice says that we need to do the work in our communities to heal and to build non-carceral alternatives, but we simultaneously have to struggle for more housing, progressive education, health care and less violence in our communities by the state.

Paths to transformation

In 2020 it was a lot of talk about the abolition of the police and the prison, which I think we need. But our problems are not solved just if we abolish the instruments of this system, because it will find new methods of violence. That’s where we have to think how even the police or prison abolition needs to be a part of the process to make this a more general and intersectional class question.

This work has been done by many abolitionist collectives and networks.

Abolition politics grows through collective action. That’s also a way of hope. In regard to the struggle against the plantation, there were people who believed in the abolition of the plantation as well as some who didn’t. There were maybe some people who also lost hope that this will end. But the force is in keep moving, and I think that’s what abolitionists, specifically abolitionist feminists, need to do.

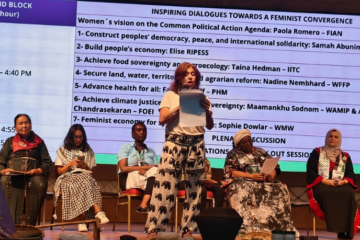

This is an edit of the speech given by Vanessa Thompson during the debate “Feminist Struggle to Confront Racist and Patriarchal State Violence”, that happened on March 31st, in São Paulo, at the Sempreviva Organização Feminista (SOF), a Brazilian organization that integrates the World March of Women.