On April 26 and 27, the Berta Cáceres International Feminist Organizing School was dedicated to building knowledge grounded in the struggles in defense of Mother Earth. Grounding spirituality moments (místicas) connected participants to the meaning of these two days, as they read poems and sang chants of resistance, sharing symbols and elements of life, such as water, fire, earth, and seeds.

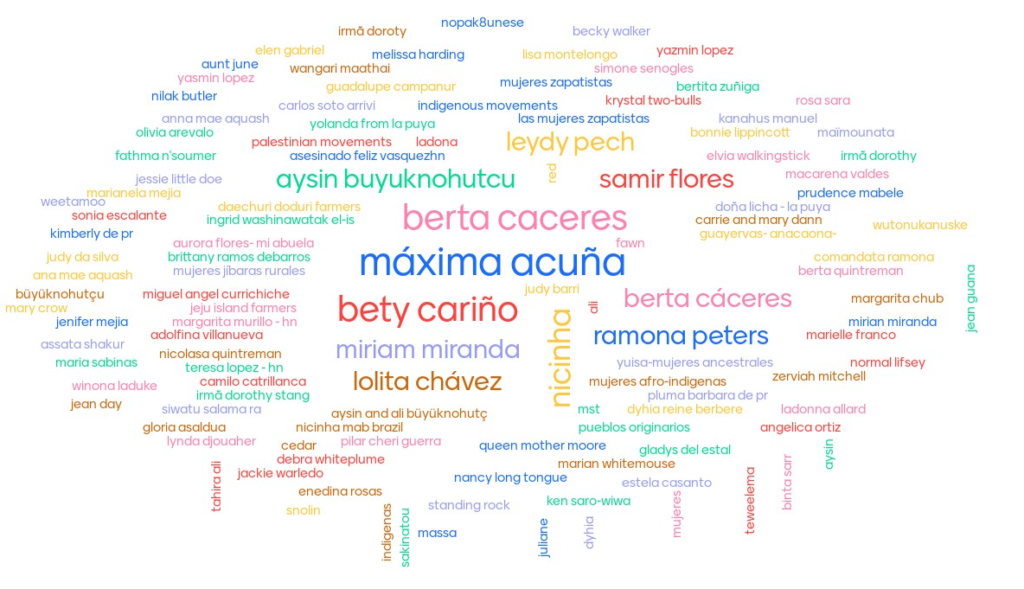

Everywhere in the world where capital moves against our bodies and territories, there is resistance. The words of Berta Cáceres call us to build our movements coherently with the demands of communities, with the strength and creativity of the peoples. Women are boldness and hope, they put their bodies in the struggle, and they are targeted by violence and criminalization. From all around the world, the militants shared the names of women who had their lives taken from them in the struggle, and those who have been threatened and persecuted, building our living memory.

During the latest meeting at the School, the groups started to reflect on how the systems of oppression overlap and operate over our lives and nature, and on the forms of domination perpetrated by white men and capital that subject territories and peoples to multiple types of violence.

We are nature. With worldviews of different Indigenous and traditional peoples, with experiences and wisdom of peasant women, we learn how to take on the responsibility to care for life in its entirety, and to share this care as a collective responsibility.

Nature is being attacked by capital, and this means that the basic conditions of life are threatened. A powerful panel introduced to us different political struggles and perspectives that converge in the defense of nature/Mother Earth.

Karin Nansen, of Friends of the Earth International, recalled that, when we fight for the right to water, we are putting the struggle for protecting water cycles and streams on center stage. And this means that healthy territories are necessary in order to have clean water as a right. Our struggle, therefore, is not just about access, but it is unequivocally connected to fighting commodification and privatization, according to where we live in the world.

Our alternatives turn the spotlight on how important the State and community-based management systems are, in terms of alliances between governments in a perspective of integration of peoples, as well as the relationship between public and community.

We are living a moment when capital moves forward by increasing commodification and financialization. Transnational corporations and international organizations leverage greenwashed initiatives. They build a shared discourse and legal architecture for “nature-based solutions,” which effectively mean furthering land hoarding and increasing their control over the peoples.

Janene Yazzie, of the Diné people, explained how these mechanisms of green economy are expanding the control and monopoly of life, plundering and forcing the peoples out of their land. She explained how “environmental conservatism” is profoundly patriarchal and anchored in white supremacy: as it allegedly claims to protect “pristine” nature, it destroys the ways of living of Indigenous peoples, banning them from interacting with their own territories in harmony and balance as they have always done. Our struggle is not limited by the discourses of a “human” right to water, because we are facing a battle around who is acknowledged and respected as human.

The violence perpetrated by transnational corporations, which grab land for their extractivist projects, is a continuation of colonial dynamics. Colonial extractivism was implemented by exploiting the labor of enslaved Black people, and it is perpetuated to this day with precarious labor and debt – owed by people and countries. Water, air, and soil pollution contaminates bodies, the destruction of nature intensifies the genocide. “When will Black people see justice?” Juslène Tyrésias of La Via Campesina Haiti asks. She called for organizing as the only alternative to fight the power of transnational corporations and State violence.

Sisters of different Indigenous peoples brought their stories and memory to the conversation, as well as their language and heritage, which organize their forms of fighting and resisting. Language is politics and organizes worldviews, this is why it is a central aspect of the strength of Indigenous people who are resisting.

Resistance is local, but it becomes stronger with international solidarity—this was an aspect the discussion groups underscored a lot. Culture, grassroots education, and communication were shared as strategies to fight information blockades from corporations and States. Based on each experience, it became increasingly clear how political authoritarianism goes hand in hand with market authoritarianism, using militarization and terror to control the peoples and exploit territories.

Women’s safety and autonomy are threatened when water and food systems are attacked and polluted. We learned how alternative production approaches, particularly agroecology as a strategy for food sovereignty, are fundamental for resistance. These are not simply opposing discourses, but they are practices, views, and forms to sustain shared life, which represent the basis of our alternatives. Building political organizing along with the sustainability of life in the territories poses challenges in terms of the timings of life, production, care, and politics, a fundamental aspect of feminist economy as an emancipatory project.

Amid so much violence, we listened to experiences of organizing, resistance, and struggle, of victories in everyday life and structural victories, of persistent organizing. All these experiences leave us with lessons learned, strengthen and inspire us, and renew our hope.

This is the case of the peaceful resistance in La Puya, Guatemala, where for years women have put their bodies to fight and stop a US mining company from exploiting gold in their territories. Sisters from Cajamarca, northern Peru, exposed how the authoritarian government has opened their territories for transnational miners, agribusiness exporters, and oil companies, and they talked about how it’s peasant and Indigenous communities who resist to protect nature, especially headwaters (cabeceras de cuenca). Women farmers from India are fighting against neoliberal legislation that impacts their possibilities of economic autonomy, against the dismantling of local food markets, and the opening to transnational corporations, while also struggling to have their work as farmers acknowledged. And, from Turkey, sisters reported how they are standing up for water streams and nature, as they are concerned with life for present and future generations.

We were inspired by the struggle of Indigenous women from Turtle Mountain, North Dakota, which were able to ban fracking from their territories, changing their lives and the possibilities for the future. They resist adamantly, dancing, organizing, and mobilizing, as the Standing Rock Sioux struggle against the pipeline shows:

Defending Mother Earth and sovereignty over our territories is an element of feminist economy as a strategic project, and it is connected to our struggles for autonomy over our own bodies and sexualities. This will be the focus of the next session of the Berta Cáceres International Feminist Organizing School.