I am a Senegalese native, and for the last 20 years I have lived on Turtle Island—more specifically in Detroit, Michigan, the ancestral and contemporary land of the Anishinaabe, also known as the Three Fires Confederacy of the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi peoples.

Detroit was first colonized by the French in 1701, and later taken by the British in 1760. Its history has been shaped by European colonialism, including the displacement of Native peoples and the subjugation of Black communities. During French rule, 25% of Detroit’s residents owned enslaved people. The local economy at the time was rooted in the fur trade—a system of extraction built on the exploitation of land and human life.

Yet Detroit has always had a spirit of resistance. It was a major stop on the Underground Railroad—a final point of passage for those seeking freedom in Canada. Today, if you visit the riverfront, you’ll see a statue of a Black family gazing northward across the water, yearning for freedom. That image captures the contradictions we continue to live with: cognitive dissonance between oppression and hope.

Detroit is a majority-Black city—home to over 87% Black residents—and yet it experiences the sharpest edges of colonialism, capitalism, and neocolonial neglect. On any given day, over 4,000 families in Detroit lack access to water. The city is a food desert. Many residents live more than five miles from the nearest source of fresh food. Detroit Public Schools, which serve over 50,000 students—90% of whom are Black—still lack the resources necessary to ensure a quality education. These conditions are not accidental. They are the legacy of structural racism and economic abandonment.

As an African immigrant, I experience colonialism and neocolonialism daily. We are constantly asked to prove our worth, our knowledge, our credentials. Our education is questioned. Our leadership is scrutinized. The result is that many of us overextend ourselves—pushed to be twice as good just to be seen as equal. This psychological toll often manifests as imposter syndrome, a silent burden carried by countless Black professionals who are told they must do more, speak better, and achieve higher to matter.

We see this violence extend to the streets—especially in the form of over-policing and criminalization. The killing of George Floyd was not an anomaly. It was a symptom of a system that surveils and targets Black bodies. Despite making up only 14% of the U.S. population, Black people account for over 25% of those incarcerated. Whether you are African American or an African immigrant, these systems affect us all the same. Indeed, statistics says that black immigrant amount for 5% of the undocumented however they represent between 20 and 26% of those incarcerated, detained and deported.

Colonialism doesn’t stop at national borders—it operates globally. In Senegal, where I was born, we’ve had multiple administrations since independence, yet we are still grappling with how to define our democracy on our own terms. We must return to our indigenous practices, our ancestral wisdom, and reject the extractive models of capitalism that continue to impoverish us.

Africa is not poor. It has been impoverished—by greed. The continent is rich in resources, which is precisely why it has been targeted by exploitative global powers. As long as the West continues to mine, pollute, and extract under the guise of development, African communities will struggle to self-sustain. And as long as that exploitation continues, people will migrate—crossing borders or seas not out of desire, but survival.

Let us be clear: if countries could keep their resources, they would keep their people.

Take the Democratic Republic of Congo. It has endured decades of conflict, not because of internal divisions, but because it sits atop some of the richest mineral deposits on Earth—resources that global industries depend on. Congo’s instability is a manufactured for profit.

We need new models of governance rooted in our own traditions. Democracy cannot only mean elections or Western institutions. It must mean collective decision-making grounded in justice, care, and self-determination. The world is at a breaking point, and our survival depends on reimagining power—not just reforming systems but transforming them.

We must dream beyond the structures that have failed us. We must build relationships, solidarity, and sovereignty across borders. And most importantly, we must return to the land—not just physically, but spiritually, politically, and ecologically.

The future is ours to shape—but only if we claim it.

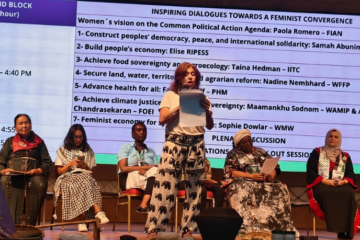

Dra. Seydi Sarr is a militant of the African Bureau for Immigrants and Social Affairs (ABISA), an organization that works for immigrants rights in the United States. Thus article and an edit of her speech during the webinar “The Impacts of Colonialism in Africa and Afro-Descendant Communities”, organized by the International Feminist Organizing School (IFOS), on March 4th, 2025.