The systemic social changes demanded by grassroots movements have led to the accumulation of numerous historical experiences and emancipatory practices that interlace with each other. The political coordination of joint efforts and popular education are core strategies to empower and amplify feminist organizing. This is why they must go hand in hand. Through alliances and educational processes, feminist and grassroots organizations deepen their perspectives and radicalize their agenda and actions, formulating new horizons.

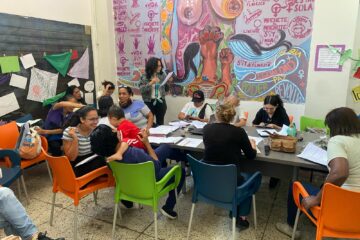

Between May 5th and 7th, 2024, militant women with several movements that take part in and build the process of the ‘Berta Cáceres’ International Feminist Organizing School (IFOS) came together in Antigua, Guatemala, for another stage of coordination and reflection. “The school is a response to this strategic need for political education to empower movements and build a plural and feminist political subject,” coordinator Sandra Morán, from Guatemala, says.

The meeting allowed fruitful reflections about political practices and shared strategies. The methodologies of popular education have helped identify specific characteristics and different perspectives among the organizations involved, aiming to build syntheses and shared pathways. “We are weaving our joint efforts, our experiences, and also our failures to learn from them and continue to test alternatives that come from social bases and that aim to solve contradictions we have in our movements,” Cindy Wiesner, the director of Grassroots Global Justice Alliance (GGJ), from the United States, says.

“This space, built through tenderness, love, and complicity, enriches us and helps us rest from what we also demand from ourselves. Nalu always said that,” Sandra recalls as she talks about the importance of the bonds of trust built in educational spaces and about the contributions of Nalu Faria, who was there when the IFOS was being built since the beginning of the process, in 2018.

An Educational Process That Is Continuously Being Built

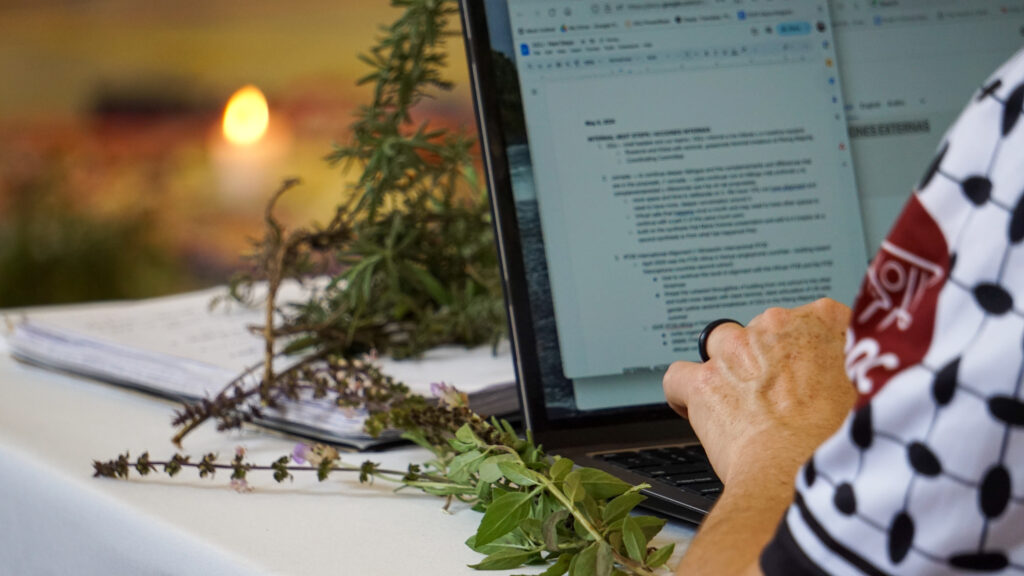

“Weaving our emancipatory proposals” was the title of the Guatemala meeting, where the goal was to share methodologies and agendas of grassroots feminism as part of the preparations for the next activities of the School. “We’ve had very honest conversations about our own challenges within organizations and movements,” Cindy says. The participants also shared analyses and aimed to find common answers for the regional and international scenario of war, genocide, criminalization, impoverishment, and the set of attacks perpetrated by capital against life.

Grassroots feminisms are all in tune with each other, each with its own specific characteristics.

Cony Oviedo

In August 2024, the IFOS will hold in Honduras a new edition of its School of Facilitators, a fundamental step toward multiplying wisdom-knowledge and practices of learning in each country and territory. In May 2025, a new international edition of the School will take place in Kenya. After a time when all activities were happening online, going back to on-site international activities allows an exchange between social movements and generations of militants, as argued by the Cuban-born Gina Alfonso, of the Research Group Latin America: Social Philosophy and Axiology (GALFISA).

We already feel like part of a community that is starting to be woven together.

Sandra Morán

Since the 2023 IFOS edition held in Honduras, the process has been involving organizations that are part of the Continental Day for Democracy and Against Neoliberalism, a Latin American and Caribbean platform that brings together union, feminist, peasant, and environmentalist movements, and others. “The IFOS is an instrument that we build in alliance, which reflects the accumulated political thought from organizations, and which becomes richer and richer. It is really a space that is full of life,” Sandra says. The challenge posed to the School is similar to the challenge identified in the Continental Day, as told by Nadia dos Santos, of the Union Confederation of the Americas (CSA): to make sure discussions are not restricted to the regional level and are able to connect with the reality of each of the national and local organizations linked to the platform.

Feminist Economy as a Strategy

The School has also been a rich space for formulations about feminist economy—which, as Cindy argues, “has to come from the grassroots, has to be plural, emancipatory, and diverse, with a very clear proposal for life against all our enemies that sustain the systems of oppression.” At the School, grassroots feminism is not treated as just an axis or a topic that is restricted to women and gender-dissident people.

Feminist economy is an alternative to this racist, homophobic, patriarchal, and colonial system. We have been proposing it and collectivizing this proposal for decades in our struggles and in our work of creating alternatives.

Cindy Wiesner

Increasing debt and impoverishment dynamics are fundamental pillars of the imbrication of capitalism, racism, and patriarchy. Tackling the agents of capital and their exploitation practices is necessary to change the balance of power in the capital-life conflict. To do so, we must look into capitalism through a feminist lens, Gina says.

Food sovereignty is also a horizon articulated with the feminist economy proposal. “The food sovereignty project can save not only agriculture—it can save humanity,” states Wendy Cruz, of the Honduran organization 25 of November, linked to La Via Campesina and the World March of Women. At the School, the participants created a true mosaic of interconnected struggles, bringing together the forms of resistance and alternatives their organizations propose. María de los Ángeles, of the Movement of People Affected by Dams (MAR, in Spanish), for example, addressed the connections between feminism and energy. What proposals of feminist economy do we want and how is it combined with a community-based energy model focused on good living? Her questions met with those raised by Mercedes Gould, of Friends of the Earth Latin America and the Caribbean (ATALC), who shared the proposal of just and feminist transition.

Nothing is set in stone. Through processes of conversations, meetings, and education, we build this other possible world we dream of.

Cony Oviedo

“When we talk about life, we are not simply talking about women or people. We are talking about all lives that exist on this planet, and about how we are centered around them. We think about the care with nature, about more just, solidarity-based relationships where reproductive labor is recognized and reorganized,” Cony Oviedo, from Paraguay, and a member of the World March of Women International Committee, proposes. The patriarchal dichotomies, like the one that establishes hierarchies between human and non-human life, are part of the problem and must be challenged through a political proposal that reaffirms the interdependence between human beings and our ecodependence on nature.

In this sense, the patriarchal separation between body and mind is constantly challenged in feminist educational processes, both in discussions and in the approach to women’s bodies and sexualities, as well as in creative and bodily methodologies of learning and discussion. As an activity based on popular education, there were also beautiful moments of mística, when participants were able to learn more about other cultures and territories, as explained by Andrea Ross Beraldi, of ALBA Movements.

The meetings in Honduras and Guatemala show us the tasks we have to fulfill, because there are very profound discussions that we need to take to our organizations to build them from the base up. They feed back into our national and regional processes.

Wendy Cruz