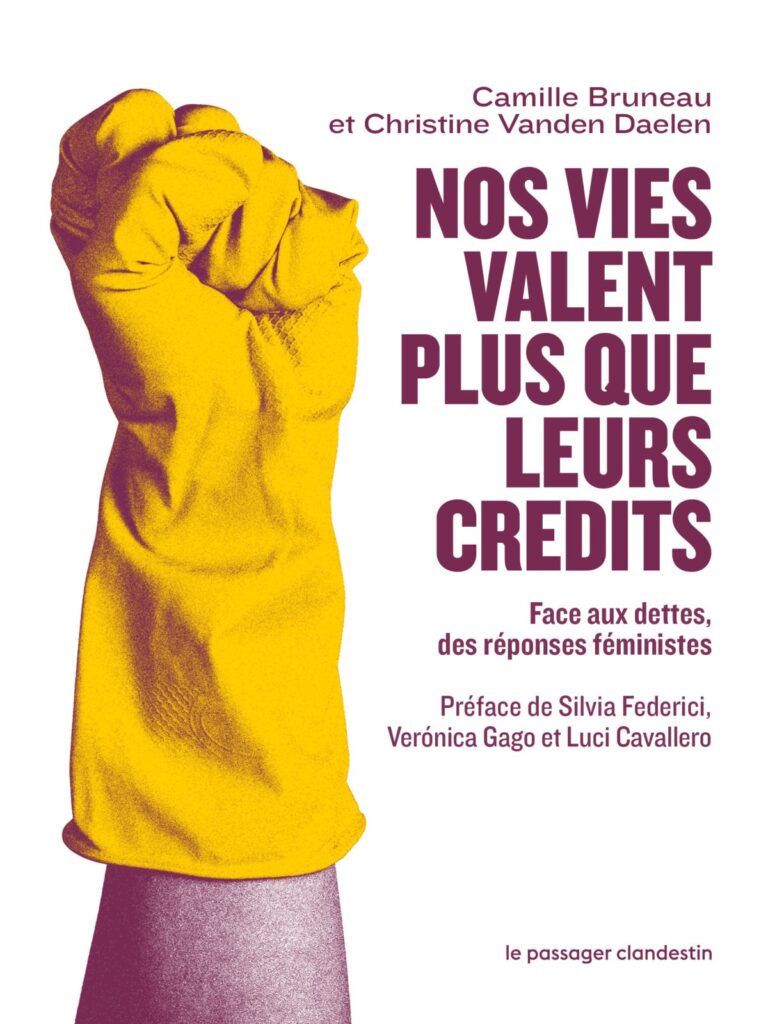

Feminist readings on the economy place the sustainability of life as a starting point of analysis. This allows us to turn priorities around, formulate new questions, and propose new alternatives. As states and people face increasing debt, feminism has been treading this path in different parts of the world, as described on the pages of the book Nos vies valent plus que leurs credits – Face aux dettes, des réponses féministes [Our Lives Are Worth More Than Their Credits—Feminist Responses to Debt]. Debt is presented as one of the mechanisms of capitalist accumulation, and it is challenged based on women’s—collective, private, and political—experiences.

In an interview granted to Capire, the authors Camille Bruneau and Christine Vanden Daelen talk about the collective process of building this formulation since the struggles against the austerity policies ensued after the 2008-09 financial crisis, addressing ecofeminist struggles and struggles around social reproduction. The conversation that fed the writing comprehended the evolution and diversity of feminist struggles and the organizing process of the Committee for the Abolition of Illegitimate Debt (CADTM). The book is a tool for internationalist feminist struggle, showing the power of political actions for debt cancellation and introducing possible ways out that counter the narrative that renders the traps of debt natural. Read and/or listen to the conversation between Capire and the authors.

Why is debt considered illegitimate?

Christine: This book is based on the premise that we are talking about illegitimate and odious debt. Overall, what does illegitimate debt mean? It means debt that is not used to fund or meet the needs of the populations. On the contrary, it directly feeds the profits and interests of lenders.

Unfortunately, the vast majority of debt is illegitimate, both in the South and the North. These illegitimate debts feed off each other, in the sense that, in the name of the debt, austerity and structural adjustment policies are imposed, generating a recession that forces states to resort to incurring more and more debt. Illegitimate debt thus creates a vicious circle and if it is not stopped, it will only produce social devastation, overwhelming austerity, and destruction of all collective well-being.

Camille: Not only that, there is also the notion of odious debt—that is, debt that does not serve the interests of the population, and of which both lenders and borrowers are aware. It is not just about admitting that “we made a mistake.” If that happens repeatedly, it’s because it has become structural, feeding capitalism and strengthening inequalities. This is why we argue that it is criminal. There are several legal norms and arguments explaining why these debts should not be repaid. These arguments have been used in public debt audits, such as the case of Ecuador, for example. There are other arguments in international law, like fundamental changes of circumstances and force majeure, for example. This is why it is necessary to show that these debts can go unpaid, and this is what we are trying to point out in the book.

It is an invitation to overcome that feeling of a nearly “moral” obligation, where we tell ourselves “we are in debt, we must repay it,” and remember that we can legally demand the cancellation of illegitimate debt.

How do different elements of colonialist and heteropatriarchal capitalism—that is, natural resource extraction and exploitation of waged and free labor—fit together in the systemic logic of debt?

Camille: Debt is really a tool to strengthen the hoarding and extraction that capitalism establishes to create accumulation. Whether by saving money through unpaid labor or increasingly undervalued labor, whether by exploiting natural resources or workers at an increasingly fast and devastating manner, debt is the instrument that will allow speeding up this necessary process for capitalist accumulation. This is the result of having eliminated the value of these processes: the regenerative capacity of nature and social reproduction that is primarily carried out by women, but also in general by peasants, by all people who care for the world and others, and by all essential workers. The ruling—and therefore heteropatriarchal and capitalist—culture downgrades these processes and activities so it can exploit them more and more. And debt will justify the fact that wealth should be extracted from all these things that are considered infinite, worthless, and extensible, at a faster and faster pace, to finally create the necessary monetary value to repay it.

We see debt as a continuation of colonization, as a tool for continuous colonization, not only from North to South, but also affecting all these marginalized bodies and all these processes. What we effectively propose is to read all these things in conjunction.

Christine: Debt colonizes women’s innermost lives, as Verónica Gago, Luci Cavallero, and Silvia Federici point out in the preface of the book. It is important to understand to what extent debt penetrates homes and communities where their well-being and often their own survival is a responsibility patriarchy assigns to women.

As the social state and public services are destroyed in the name of repaying public debt, any increase in public debt means increasing private debt for women. To offset the lack of public support to social reproduction and continue to secure the survival of their loved ones at all cost, more and more women are falling into the hellish downward spiral of over indebtedness.

This way, debt colonizes women’s private and everyday lives. As they incur more debt, they become more and more insolvent, therefore experiencing a specific kind of violence: we are talking about debt slavery and debt-bonded prostitution. We can see to what extent, beyond concepts, in women’s private lives, debt has criminal, violent, and sexist consequences.

The examples of concrete cases in different countries is a very interesting aspect of the book. What is your take on the role of anti-debt struggles in different anti-capitalist strategies in countries in the North and South?

Camille: Debt has such concrete consequences in people’s lives that all struggles can usually have something to say about debt and austerity, in a way that is coherent with their contexts and experiences. I have been to Senegal at the seminar on microcredit, and although each testimonial referred to individual cases in specific places, we could almost always establish a relationship with the fact that public debt has increased and this has been taking women to experience very concrete situations.

In my opinion, what can really be reinforced is this relationship with public debt, which allows us to internationally have common demands regarding debt cancellation. Ultimately, what the women from Senegal experience in terms of microcredit is not only connected to microfinance institutions, but it is also closely connected to what we, as Belgian or French women, could have demanded to our own governments. We can and must demand the end of austerity in our countries, but also demand the cancellation of debt in Senegal, for example. So the demands for cancellation in other countries can also be translated as demands for cancellation in our own countries.

Christine: I was lucky to have had contact, in the past 20 years, with feminist movements at an international and European level, but also in Belgium. I could see to what extent feminist movements have taken on the issue of debt and how they have managed to personalize debt-related matters. How it affects women for all the reasons that we go through in the book, in their daily lives in a very concrete way—feminisms have taken into account the experiences of the people who have been the most affected by debt and experiences that are often rendered invisible or are not listened to, because we are in a patriarchal system. Over time, the feminist movements came up with answers that are sometimes much more innovative, especially in terms of struggles against debt, than the anti-debt movements themselves.

Can you give us some examples of this kind of feminist response?

Christine: For example, the feminist strikes that highlighted all the invisible labor. If we ask why this work is invisible, we ask what the systems of domination that turn this work invisible are, and then we get to the capitalism that is fed by debt. The fact that I was working on the topic of feminisms when I was doing militant work for debt cancellation allowed me to go from concerns related to “macroeconomics” to areas that are more connected to what is experienced, what is living, the personal, and women.

Camille: Regarding debt, feminisms continue to do what they have always done—that is, they lay bare and turn into collective what was considered private and intimate. They conduct a structural, collective, and political reading on debt, as does the CADTM. Feminisms allow us to argue that debt is not an individual problem to be resolved individually, that it is not a matter of shame or bad luck or some failure resulting from poor budget management or miscalculation that we should resolve on our own. Feminisms were able to show that debt is the result of structural political decisions and logics from a deeply capitalist and heteropatriarchal culture of domination.