Technology has become less alienating and less patriarchal since women started to engage with it.

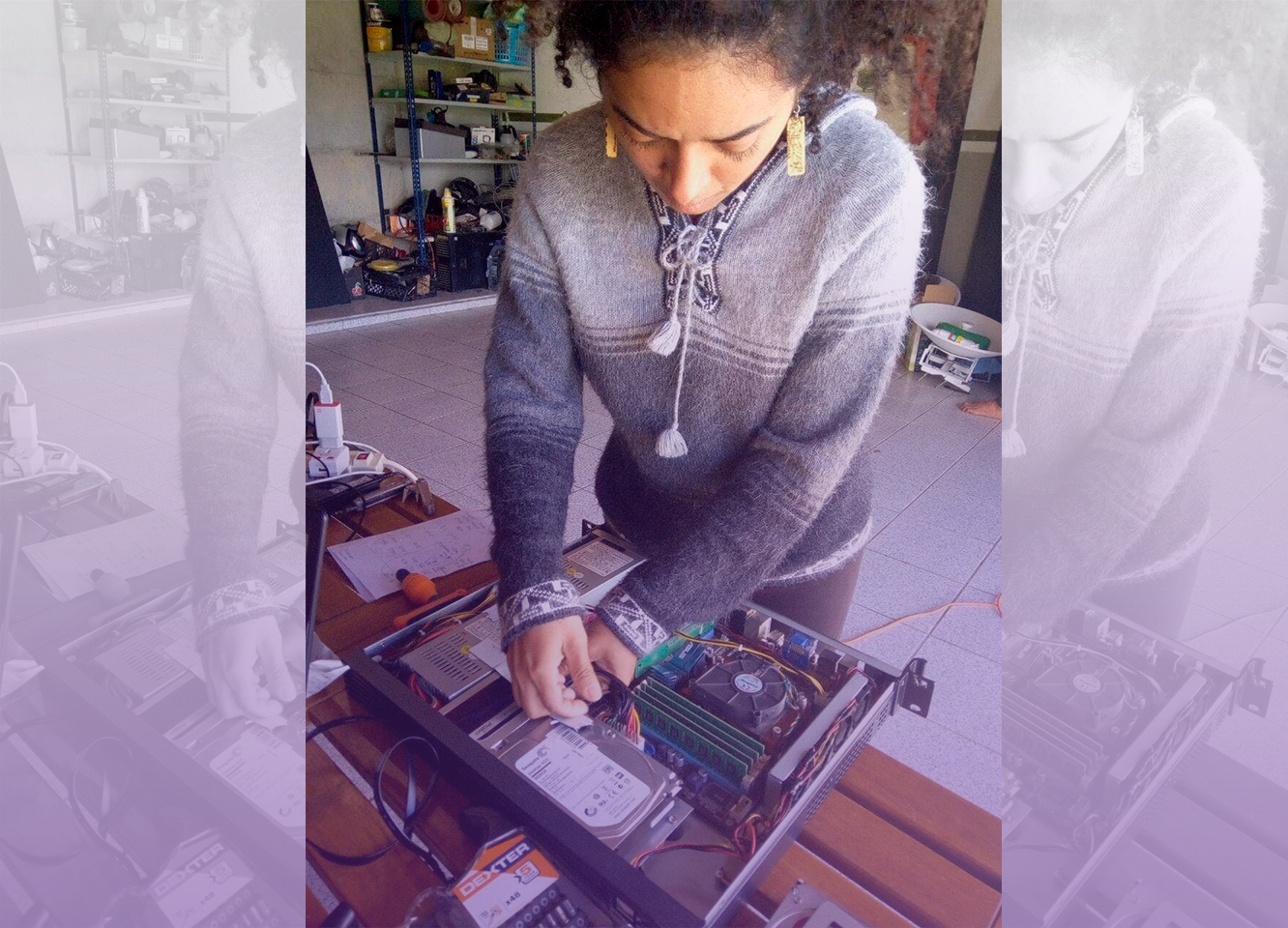

Since Nikole Yanes got her first computer at age fifteen, she has been fascinated with technology, and she has been especially interested in free software. A Honduran feminist activist, Niko is a member of Código Sur, a Latin American collective that, for more than fifteen years, has provided new strategies to make free communications, culture, and technologies more accessible, in order to strengthen social movements and produce narratives and technologies that can create possible worlds that can be different and more equal. Nikole spoke with the Capire team about free, alternative, grassroots feminist digital technologies.

Everything that is virtual can be traced back to the physical world, and this is why Nikole talks about perspectives that can challenge energy consumption, extractivism, and surveillance, which has increased the persecution against social movements. Read the interview or listen to our conversation (in Spanish) below:

There is a lot of debate about technology and going digital from a perspective of understanding corporate power—in other words, about how the dynamics of big corporations impact the internet and social media, about racist algorithms, about how they lean toward far-right content… All of this is very worrisome, but we would like to start our conversation from a different perspective, so our first question is: are there alternatives?

We are constantly trying to find a different world, with a respectful worldview or world practices that can be in harmony with our surroundings. I think that women have always pursued that line, because even though women have always been in charge of care, that is not necessarily a bad thing. The issue is actually the stereotypical views about who should be in charge of care. I am talking about this because when we take a tool, we see that we can use it to take care of and respect the environment—and that includes land, community, and family, but also technology. I believe that this is an alternative that has been put forward by feminism for technologies too, and it is part of how we conceive these alternatives and also from the places where we are building them.

How can we organize collectively to challenge capitalist monopoly both on food and technology? We know that technological capitalism is very strong and can be very harmful to our lives and the environment. So there are many alternatives emerging in face of that. Código Sur is one of them, but there are many others, and it’s great that they continue to grow.

Our proposed idea is to create a community-based, collaborative internet infrastructure, in which we can respect each other and find better ways to implement it. But this is not the only alternative technology out there. For instance, there are community internet networks, which are located in specific areas, and also other alternatives, which are related to today’s different kinds of digital communication—algorithms, search engines, browsing, mobile telephony, hardware, software… A number of alternatives are being created to face this logic that wants to privatize knowledge and make too much profits off of these tools. And obviously, the alternative is intersectional, because it is anti-patriarchal, anti-capitalist, anti-racist, and community-based.

Could you explain what community-based infrastructure means?

Imagine we are in our community, our neighborhood, and we are holding a meeting. We then say, “Ok, so what do we need?” “I need an email,” one of us says. The other one says, “We don’t have a website for our collective, so we need one.” And another one, “Well, for the radio station, we need a streaming platform for our feminist podcast.” So instead of having one computer (which is a server) for each one of them and having to maintain several computers, which would be a lot of work, they collective decide: “Well, since all of us want different kinds of tools, why don’t we use one server and share the resources, share our efforts, our knowledge, and our time?” This way, we can actually dedicate more time to our podcast, our activities. Each of us dedicates a little bit of time, we share responsibilities and resources, and understand that, this way, we also carry out a transformative work with the contents we produce, the tools we use. Not only that, for us, creating community-based infrastructure also means using free software—that is, setting up a server using free software—and that has to do with our safety and security, because we know that our data and information must be protected.

From this community-based infrastructure, we contemplate different ways to engage with technology. This relationship has not been easy, because it is a struggle against how technology has been colonized. So we are decolonizing it, but we are also creating new ways of existing with technology. We are constantly looking to find out how we can make a better use of it, how we can create new narratives, and how we can make our struggles stronger—which is the most important thing. I think this is what community-based infrastructure translates to.

One thing we worry about is energy consumption and the extractivist practices that support a capitalist approach to digital. How can we look into this from a grassroots alternative point of view? What are the technical and political decisions that can be made to help us critically reflect on this physical aspect of digital?

Recently, I was looking into the pollution produced by big corporations as a result of internet transmission. What is it that is producing pollution? These companies are trying to make information increasingly centralized. Centralizing information from across the planet leads to pollution, because it requires more equipment, more energy, more devices to connect, different devices in different locations, to make that information accessible. So one way to avoid that much pollution, if you look at the issue from a community standpoint, is to decentralize information. Our data are translated into money. But you also have to store those data and have more equipment to be able to analyze them.

When it comes to infrastructure, suppose you had a mirror, but it’s not a physical mirror, but a computer that is similar to yours, a “clone,” which works when the power goes out, for example. In this case, this machine would start running, like “nothing happened.” But what does it mean to have these clones running at the same time? It means more pollution and more resource consumption.

And where do these energy resources come from? A lot of companies claim, “we don’t consume so much oil,” because they are using more renewable resources. There is only one thing to say about that: be wary! Many hydropower plant projects are running over and destroying the wellbeing of communities. Obviously, large capital is trying to make this look good, saying, “don’t worry about all these machines connected here, this energy comes from a hydropower plant,” but they fail to mention that hydropower plants criminalize communities and kill a lot of people.

You will find many different things in community-based alternatives that oppose this model. I believe that each community could manage their own infrastructure. This means that, if our community has enough sunlight, we could manage it with solar. If our community has enough water and other kinds of resources, we could manage them in a more community-based way, and so we would not consume so much resources.

Even in terms of pollution, we need to think about the places where our data move through. For example, if I am in Brazil and I have a server connected in Brazil, I would use less energy and less resources if I connected directly to it rather than connecting to a server based in Europe or Asia. This is a very difficult issue for Latin America, because our broadband supply is very limited. They are limiting our use of our own resources so that we have to consume from other places, while at the same time using up our resources. There is a study I love, conducted by Kalindi Vora and Neda Atanasoski, which looked into all submarine cables that carry telecommunication signals to Latin America, and they found out that these cables also follow the routes of colonization. This product of colonialism still has a great impact on us today, as they continue to steal our resources to keep their internet infrastructure. And that also means that we are not able to have our own technologies because of online inequality. The internet and the speeds we have here in Latin America are not the same as in Europe and other countries up north.

There is a lot we can do about this. In communities and collectives, this is what we are thinking about: having our own local teams, which can access information more quickly and through balanced energy consumption, which carries implications for our uses and organization.

To reduce pollution, the truth is that those companies should not exist. Capitalism should not exist, and hopefully it will continue to fall, more and more, but what we see in technology is that corporations are creating more and more capital. It is important that we stop using certain services that manipulate and monopolize information. Just like we do with food—when we don’t buy products with GMOs, we end up buying from that lady who grows lettuce or finding other alternative products near us. And does that mean something changes in our lives? Yes. Are there alternatives? Yes, there are. This planet needs a break, and that also includes turning to alternative technologies.

You are providing us with this systemic view, which is a huge contribution for us to think about the challenges we have ahead of us to face big corporate power. In our continent and elsewhere, social movements are very concerned about the criminalization of those who struggle, and that has to do with the fight over territories, but it is also becoming more dangerous with surveillance technologies. In the Americas, how can we think about digital protection and care in our movements, especially us, feminists?

Digital care has always been about respecting human rights and equality. To us, that means that, when we develop technologies, all approaches must be connected with each other: the equipment we buy, their use, and the knowledge we have about the tools we are using, and what they can be used for. There are a lot of important questions to be made, even if sometimes that means taking more time and work to do proper research. Two examples include reviewing the privacy policy of the tools we use and decentralizing our information. Keeping this balance is important, like, “Ok, we use these tools because we want to share information, but they are not our allies.”

We also need to learn why technology is patriarchal, why it colonizes our lives, and what damages it causes. We talk a lot about appropriate, strategic use of these tools, so they don’t wear us out, because it’s important to maintain a balance between the street, the internet, our home. Having a balanced use of technology is also a good way to care for ourselves, as we are aware that it is not a welcoming space for us.

The internet is a very violent place, and I would like to say it is not, but, in the end, it is what it is. For women, the streets are also violent, aren’t they? So when we take to the streets to protest, we often need a protocol of what to do in case there is a clampdown. So it’s the same thing. What are we going to do when, for example, we want to go online and talk about legalizing abortion? How can we protect ourselves from online harassment? We know that they don’t agree with what we are saying, but they may be listening to what we are saying anyway.

What I think is the most important thing is: to know the strategies and care for our information—from creating very strong passwords to choosing the tools for different kinds of activism, to pursuing a harmonious relationship between our work and our safety and security. There will be obstacles along the way, so it’s always best to be prepared for them, so that, when we do face them, we are able to do it in an organized, collective way. We are not alone. There are many women who are thinking about ways to hack the patriarchy online and create alternative solutions to make the online space safer for everyone. And this requires a combination of individual, collective, and organizational practices in terms of technology.

We often find it hard to start a conversation about technology in collective spaces because it is something perceived as being just for experts, and the mainstream debate is always very alienating. What you are saying about protocols and collective organizing shows that you are already working on strategies to build feminist technological autonomy and sovereignty from the bottom up. But it also makes us think about the challenges that are still ahead of us. What are these challenges in terms of incorporating technology as part of the political debate and agenda of grassroots movements?

I don’t see the challenge as a problem, but rather as a motivation. The truth is that we need more women in technology. It doesn’t matter if they are doing other things or if they have a different work or career. The issue of technology is now reaching across everything we do, and it is important that more and more women are engaged with this issue. I really like to say this, because it’s about exploring, playing, having fun, finding different narratives. I was actually talking about this with some comrades who are creating a gynecology project, and I was telling them, “What if we connected it to a microcontroller that comrades can use by touch and it showed each part of our vagina, our uterus?” This is an example of how we could interact and use technology to explain those issues that are extremely important to us. Technology is not just about algorithms and networking cables.

We have so many technology tools, but sometimes we make a very limited use of them. It’s like the internet is only for Facebook or YouTube, all those big corporations that have been taking over our everyday lives. To me, the big challenge is: what do we do with this tool and what are the barriers we find when doing each of these things? For example, for us, in terms of community-based infrastructure, the challenge is about tackling the broadband supply issue in Latin America, because it curbs our ability to share information and creates digital exclusion. And I am not even talking about internet access, which is a very sensitive topic these days. So many people are offline, which could be both a good and a bad thing. For us, these are the major challenges to make this a safer space, respecting our right to privacy, freedom of speech, bodily integrity, and autonomy, and also to create our own technologies.

Yes, there are a lot of challenges in terms of production, even hardware. Today’s hardware products are made in China, and that leads to a lot of barriers. Also, cost control is a really big thing. Planned obsolescence poses challenges to making equipment last longer and to respecting the planet, the resources, and the people. I think these are some of the challenges. We, women, have a lot of work ahead of us to tackle technology. We need more and more women who want to experiment, play, and work to hack the patriarchy.

What would you recommend to those who want to learn more about this topic? What can we look for in terms of content and possibilities?

One of the most beautiful points of reference in terms of technology and feminism is about making a feminist internet from a women’s perspective and how we see technology. This part of the Association for Progressive Communications — APC about feminist technology is still echoing this debate. One thing that I would also recommend is looking for feminist collectives doing alternative infrastructure work. This video call we are making is using a feminist server, Vedetas, which is based in Brazil, for example. There is also a network of alternative infrastructure called InfraRed. More than anything, I would say that the internet needs our voices, as women. And this is why I love Capire, because it’s a way to occupy the internet with more than just content produced by monopolies. We need an internet with content for us, that can provide alternative worlds that we are already building and which we want to make reach more places, to show that there are possible ways to relate, live with, co-exist, and create hope for other possible worlds. We don’t need to go to Mars to be able to create a different planet and different sentiments toward a collective life.

Technology has become less alienating and less patriarchal since women started to engage with it. To me, based on noteworthy women who have been working with technology since the beginning, there have always been good intentions in their contributions, and always with more comprehensive views on where technology will go and why. We need women to continue to create these alternatives, and may our alternatives always pursue balance and feminist principles. Despite the troubles with the pandemic, we know that there are so many things that we need to follow, embrace, strengthen, and also create unity in times like this—which, as we know, are complex times. But we will overcome them with care and struggle.