On November 5th, the feminist organization Culture Égalité, from Martinique, celebrates and looks back on the birthday of Lumina Sophie, a leader of the Southern Insurrection, an uprising against slavery and anti-Black prejudice in the country. Paying a tribute to her memory, we share an excerpt from the publication Karbé Fanm No. 2, Lumina a.k.a. Surprise [Karbé Fanm n°2, Lumina Sophie dite Surprise], an issue celebrating the 150th anniversary of the Southern Insurrection in Martinique, published in 2021. In addition to the article telling her story, the organization also published an interactive multimedia map called On the Traces of Lumina, which you can access here. Read Lumina’s story below.

Lumina Sophie, a.k.a. Surprise!

She was born in the town of Le Vauclin on November 5th, 1848—that is, 5 months after the abolition.

Her legal birth name is Marie-Philomène Roptus. But throughout her life she will be simply called by her diminutive, Lumina, or even her nickname, Surprise. Just like her mother, in order to survive she is simultaneously a farmer (at their jaden bo-kay—a home garden), a rural worker, a trader, and a seamstress. In the beginning of 1870, at 21 years of age, as a young woman just out of her teenage years, Surprise is endowed with strong physical resistance. This is because she would take long walks every day to sell her mother’s products, offer to work for households during harvest season, take part in joint efforts, deliver the pieces she sewed…

In September 1870, she is two months pregnant, which does not stop her from being extremely energetic and active. She also has a strong personality, a strong character, a powerful energy, and great freedom to not conform to the standards of her time… She is just out of her teenage years, starting her life as a woman, when her fate changes during the Southern Insurrection.

The Southern Insurrection

In September 1870, 22 years after the abolition, the Southern Insurrection erupted.

Léopold Lubin, a young Black artisan from Marin, is insulted and abused by a “metropolitan servant.” The latter believes the man of color did not give way to him quick enough. Lubin presses charges, but the charges are rejected. A few days later, he takes matters into his own hands. He is then found guilty and sentenced to pay 1,500 francs in damages for “premeditated assault and ambush” and to serve seven years in prison in French Guiana (a sentence that was only imposed to “Africans and Asians”).

The Black population was outraged and expressed their solidarity with him, organizing to demand his freedom: a “youth circle” is set up in Rivière-Pilote to pressure authorities and a petition is launched to pay his heavy fee and file an appeal. Very quickly, traders, who had easier contact with rural women through markets, helped to pass those petitions around.

In addition to Lubin’s case, there was the Codé affair. In fact, the residents of Rivière-Pilote criticized Louis Codé, the owner of La Mauny residence, for his nostalgic feelings about slavery, for his arrogant attitude toward his workers, and for hoisting a white flag outside his home since the beginning of the year. For Black people, the white flag of the monarchy was closely connected to slavery. Finally further fueling resentment among the population, Louis Codé was publicly bragging, as a member of an all-white jury, for having convicted Lubin for daring to touch a white man.

The Course of the Insurrection

During the second half of 1870, France had just gone to war against Prussia and everyone in Martinique understood that the imperial rule of Napoleon III was using their last trump card.

On Wednesday, September 21st, the ocean liner La Louisiana confirms the capitulation of Sedan, the surrender of the Emperor, and the proclamation of the 3rd Republic. That was the spark that unleashed people’s disgruntlement, which was, until that point, somehow latent… Around 3 p.m. on Thursday, September 22nd, in Rivière-Pilote, the mayor, Auguste Cornette de Venancourt, following instructions, proclaims the Republic. Women then demand Lubin’s freedom and shout their hatred against Codé and other white jurors and judges. They shout along with the crowd, “Long live the Prussians!” Numerous crowds flock from the villages, joining people from rural areas nearby. Louis Telga (a former enslaved man, small landowner, and artisan butcher) comes back and forth from the village that day and an amazing crowd of 700 people follows him. He decides to go to Codé’s house, five kilometers outside the village.

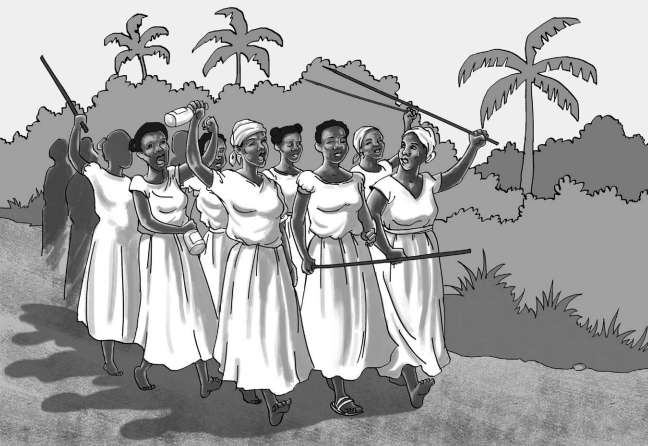

Women are there, they are active, carrying flaming torches or wielding sticks like spears. In La Mauny, the crowd does not find Codé, who ran away. The rebels set his bagasse hut and sugarcane fields on fire. That same night, between September 22nd and 23rd, around 10 p.m., the “Telga army” clashes with the garrisons of Marin, sneakily alerted by the mayor—two dead and two injured. After that moment, the riot becomes an insurrection.

The Role of Lumina and Women

The logic of social war favors the massive irruption of women in the public arena. They walk on the footsteps of sugarcane fields! They arm themselves! They fight! They take the word and the initiatives! All attitudes, aptitudes, and actions they are denied in normal times. Of the 114 women who take part in the movement, 15 are arrested.

Next to the 15 women that will eventually be convicted, there are all those from whom investigators could not hope to obtain testimonies to incriminate the “most committed leaders.” Because, in the minds of oppressors, women are easier to manipulate and more likely to give information in exchange for having their charges dropped. Reading the records of the discussions carefully, however, it is clear that they did not provide any testimonies that were particularly incriminating against the rebels, no more or less than men’s.

Moreover, heavy sentences will be imposed on the 15 women defendants. In fact, none of them is found not guilty. And the accusations, the testimonies of the accusation depict nearly all of them as Pétroleuses [revolutionary women accused of using oil to start fires], arsonists and looters. But these women did not just start fires and engaged in looting. “Of course,” they also had to cook for more than 600 people.

Lumina Sophie, also known as Surprise, was notably active. Once the insurrection was defeated, she was arrested on Monday, September 26th, in Régale, at the house of Eugène Lacaille, and taken to Fort Desaix, in the Fort De France hills. She is then less than two months pregnant.

Lumina’s Trial

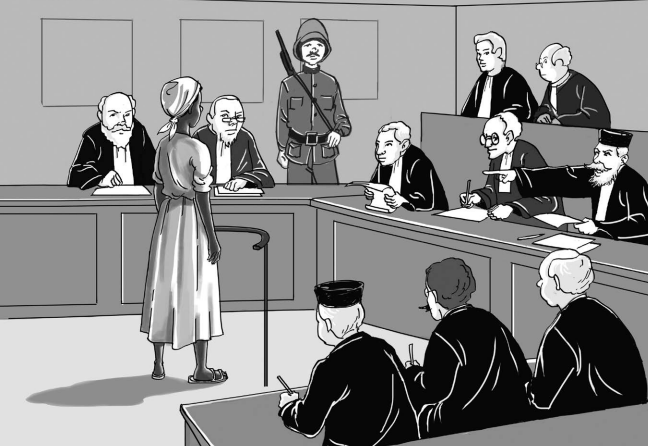

First, the court was not concerned about looking for her real name, Marie Philomène Roptus, and the records only show her nicknames Lumina Sophie, also known as Surprise. There is no concern about letting the records show her age—they claim she is 19, but she is 23. Her trial will be exclusively for the prosecution: a witness refers to her, with some disdain, as the “queen of the company” amid looters and arsonists! The governor at the time, Menche de Loisne, describes her as “the flame of the revolt.”

Actually, the court does not believe for one second that a woman could be a military leader or a conspirator. But she is charged for looting and arson. The judges punish her for expressing her hatred and her outrage against the planter aristocracy, whom she calls the enemy. More than anything, she is punished for threatening and dominating men. Because she did not conform to the image of docility, submission to men, and coyness to which all women are supposed to conform. She is some kind of monster, the anti-woman, the anti-man, the anti-mother that has to pay dearly for her outrage, because she is a bad example for other women, a threat to the family, religion, the social order, and the established relationships between the sexes. A true danger to colonial, patriarchal, and class society!

Verdict and Sentence

In April 28th, Lumina gives birth to a boy at the central prison of Fort-de-France. She is separated from her son and the prison management casually names him Théodore Lumina.

Not even her youth or her 40-day-old baby were enough to spare her from a prison sentence, in a trial held in June 8th, 1871. She was fond guilty for being a “bloodthirsty” “arsonist” and “looter” because of Codé’s killing, as well as a “blasphemer” and “leader.” She was deported on December 22nd, 1871 to the Saint-Laurent du Maroni prison. Her son later dies in prison. She passed away on December 15th, 1879. The severity of deportation, the atmosphere at the penal colony, the isolation, the separation from Martinique, undernutrition, endemic diseases—all that led to the end of the life of Surprise, the insurgent, at age 31.