Hebe is gone, and as we say goodbye, we mumble words with a lump in our throats, words that can neither express the sadness we have felt since we received the news nor the unease that comes from the contradictions we have experienced in so many moments we have shared.

Hebe is gone, and it is hard to know that the postponed embrace will no longer come. And it is hard to know it because we have shaped affections and distances, commitments and differences, passions and divergences, all equally intense, always saying what we had to say outspokenly, with no ulterior motives, looking into each other’s eyes, with persistent endearment, despite annoyances.

Hebe is gone, and I have this weird feeling, a very private and very collective sorrow. We know that her ashes will forever rest on the Plaza de Mayo, but we will no longer meet her every Thursday with her large body, her grave posture, her shout so often necessary, essential to inspire rebelliousness, and her statements, sometimes incomprehensible. But… Who are we to talk about what drove her and the way she trusted and distrusted the people to whom she offered or did not offer her love?

I will not forget that afternoon on December 19th, 2022. We were just finishing the semester at the then brand-new People’s University Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo [Universidad Popular Madres de Plaza de Mayo] when we heard that a state of siege had been declared. An assembly was immediately established by the Mothers, by us, professors who were there, and the students. A very young man, extremely respectfully asked the university director: “Mother, what do we do when a state of siege is declared?”

Hebe very calmly, yet bluntly replied, “You just ignore it.” And she explained what we would experience later, said these measures only become real when the people believes in them. In the following hours, in the Plaza de Mayo and its surroundings, tear gas canisters were shot and launched against everyone who did not believe in the state of siege, and things remained like that until the next day, when, in the middle of the morning, the world seemed to have come to a halt.

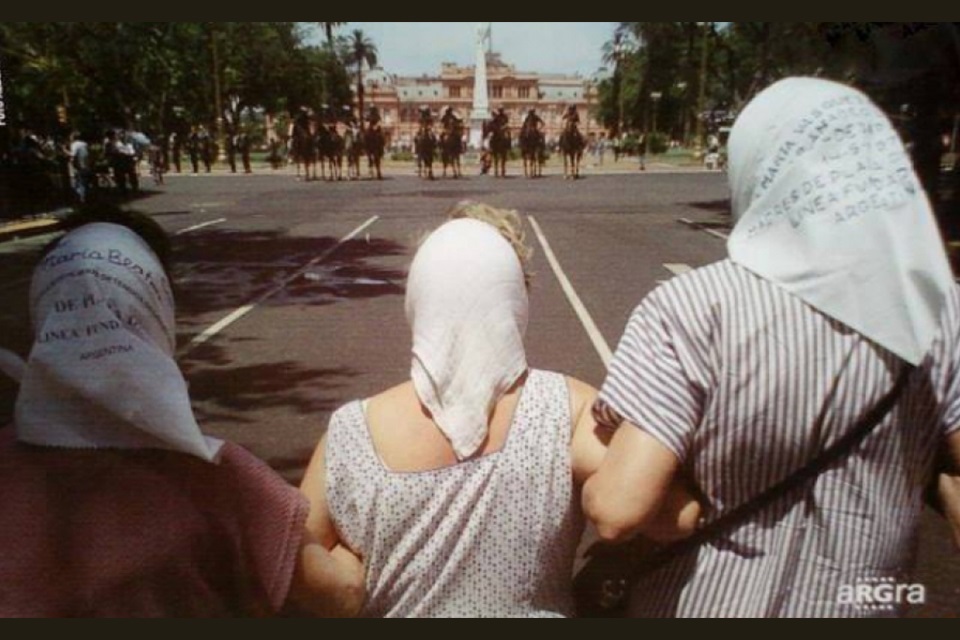

A group of the Mothers, led by Hebe, walked into the square demanding the end of the crackdown. Within few minutes, we were able to gather strength and take a deep breath. The mounted police then reacted and started to hit. They hit the Mothers. On TV, they showed footage of the bloody white scarf (pañuelo). That image really touched something deep in the Argentinian people, who took to the streets to say, “no one messes with our mothers.” Crowds started to flock into the city center. We took the Mothers out of there in a car owned by the radio station FM La Tribu and took them back to the House of the Mothers, their headquarters located in the People’s University. As if everyone had listened to Hebe’s magisterial class the day before, in which she called for disobeying the state of siege, the slogan was “state of siege up your ass!”

We had learned from Hebe and the Mothers that “the only struggle you lose is the struggle you renounce,” and that you have to call things by their names: “bread is bread, wine is wine, a killer is a killer.” With them, we shouted that day and the other days: “out, all of you—we don’t want any of you” and, as usual, “no step back.”

It was a poignant time. During that time, Hebe turned the March of Resistance into a picket. At the Plaza de Mayo, Darío Santillán and other comrades and sisters of picket organizations 1 came along, burning tires. During those years, we visited the town of General Mosconi to meet the Unemployed Workers’ Union [Unión de Trabajadores Desocupados], spearheaded by Pepino Fernández. During those years, we welcomed the struggle of Brukman and Zanon factory workers, of workers with no bosses. During those years, we visited Brazil, to attend the Landless Workers’ Meeting.

This was how Hebe and the Mothers assumed the socialization of motherhood. Those who struggled were their sons, their daughters, their children.

Hebe embraced Lohana Berkins, loving her deeply, in the struggle against the murder of travestis, and for all the rights of the travesti and trans community. Lohana was a professor at the University. There, Marlene Wayar studied investigative journalism. Diana Sacayán was a grassroots education student. All that may seem obvious now, but it wasn’t so back then. Hebe opened her arms for the people who experienced difficult situations, victims of police persecution.

Classes were sometimes interrupted and we would run out to join some protest, because the way of being was always to be there, with your full body. Other times, classes were interrupted because the Mothers had received a special gift, like a merry-go-round that they decided to put in the park in front of the University. But they were not willing to request a city license. Watching the Mothers closely was a great school of disobedience. Whenever public servants would come to take away the merry-go-round, someone would warn them and all the Mothers would run as fast as they could. As much as they could, they would hop on the horses and elephants. Who would get them out of there? These were women with white scarves on their heads representing their children’s diapers. Women who would again go around, mocking the power.

Hebe is gone. And we will continue to think about her in terms of disobedience, fearlessness, shared passions, and conversations to have. We will continue to remember how she embraced Fidel, embraced Chávez and the Latin American revolutions.

Many of us would prefer that her affections and disaffections would have taken different paths. But what right do we have to judge her faith, her ways of coping and providing unforgettable lessons about human dignity?

Hebe is gone. And how much that hurts. I can picture her cursing death, wanting to discuss whether it was the right time or if it came too early. But I can also picture her with the secret hope of meeting her children. Because she believed that she would once again hold them in her arms, in some twist of mystery.

Hebe, mother of the plaza, the people follows you on this journey and holds you in our arms.

Claudia Korol is a grassroots educator and a member of the collective Scarves in Rebelliousness [Pañuelos en Rebeldía] in Argentina.

- The picketing movement (piquetero in Spanish) was established by unemployed workers in the late 1990s and gained momentum in grassroots struggles during the 2001 crisis in Argentina.[↩]