Since a social uprising started on October 18th, 2019, Chile has lived a process of political and social change driven by social movements and citizens in general, as a response against the crisis of representation in institutional powers and against the social malaise experienced by grassroots and working-class sectors.

On May 15th and 16th, 2021, the country held a historic election process for local and regional government representatives—mayors, local council members, regional governors—and for members of the Constitutional Convention. The most surprising outcome of this election journey was the overwhelming win for left-wing, progressive, and independent sectors. Nearly 80% of the members of the convention that will draft the country’s new Constitution are critical of the current model.

Before the Uprising

The 2019 social uprising in Chile was a moment emerging from mounting anger and frustration after decades of neoliberal administration, marked by huge inequality and policies that criminalized social movements. Increasingly precarious life and poverty are also factors that motivated such an uprising. The Piñera administration further increased inequality. An attempt to increase transportation fares was the turning point that released the malaise that had been mounting for decades.

Since the early 2000s, different social movements have waged different struggles, such as the student movement, the feminist movement, and the No+ AFP [No more AFPs] movement[1], which proposed different answers for structural social problems. Meanwhile, territory-based and local organizations were emerging, even though more “silently,” which allowed to strengthen the social fabric and achieve the current scenario of social mobilization.

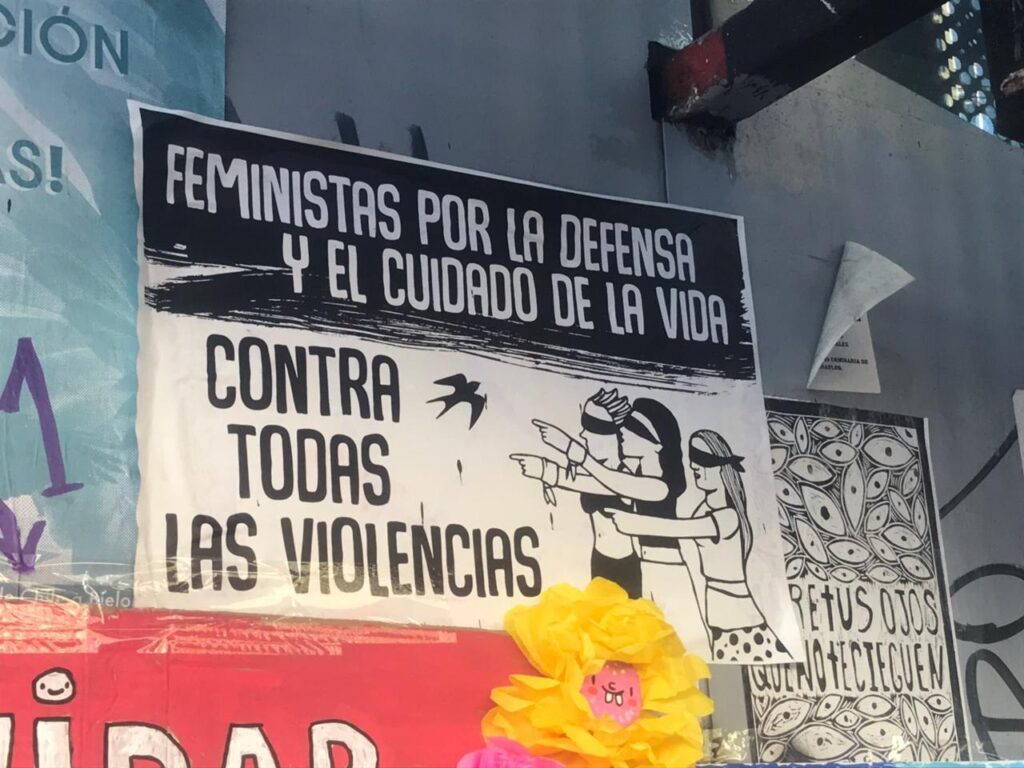

In May 2017, Chile witnessed a “feminist wave,” which exposed the huge work conducted by the feminist movement in the country. Thanks to the mobilization of high school and university students, who occupied schools and education centers, tensions were produced for the public agenda to address issues that had been disregarded up until that point, such as violence in educational institutions, gender-based violence in different territories, and the lack of progress in tackling these issues. Meanwhile, in southern Chile, Wallmapu[2] continued to be militarized, creating tensions with the Mapuche resistance as they fought to reclaim their Indigenous territories.

The silent organizing in territories and social movements started to gain exposure thanks to social media and local and community-based communication experiences, as these topics were not included on the media’s news agenda. The October 2019 mobilization was followed by an organization process in assemblies, collectives, public squares, and grassroots councils (the so-called cabildos). This has allowed each territory to promote in-depth discussions about the problems faced by Chile. Ultimately, these debates concluded that the Constitution conceived, drafted, and approved during the dictatorship was the primary mechanism maintaining inequalities in the country. The Constitution approved under Pinochet established that the role of the Chilean state was purely subsidiary and would not be include ensuring rights.

After all this process, the pandemic has made it clear that, without social and grassroots organizing, it is very difficult to survive under this system. This is why territory-based organizations have elaborated views on the future we want for women and the country. Thanks to a grassroots uprising, there is currently a huge myriad of forms of organization—networks, collectives, grassroots councils, community kitchens—who share a critical understanding about the state. The process has brought us back to rebuilding a social fabric that has been dismantled for years.

A Grassroots Assessment of the Vote

The mechanism of the Convention conducted this May had four key elements: gender parity, seats reserved for Indigenous peoples, a clean slate (which means the new draft will not draw from any previous articles), and a supermajority vote (any agreement reached by the body will require the support of two thirds of its members for approval). The election results show that the right was not even a political force in the convention, as it won 37 seats (24% of votes), less than the one third necessary to challenge their opponents’ propositions. The right will also have a limited ability to influence the convention, and progressive forces are unlikely to struggle to negotiate votes with the right.

Among progressive sectors, there are different nuances and political backgrounds, but they all agree to deny the right-wing model. On the other hand, “not being right-wing” does not mean that the proposals presented for the Constitution go hand in hand with matters such as free abortion, changes in immigration legislation, or the criminalization of movements. Left-wing sectors will have to reach an agreement about some of these aspects, respecting and integrating the discussions that have been historically built by feminism, diversities, Indigenous peoples, and migrants.

This is a decisive moment, because, after the call is made to constitute the Convention, the mechanisms for how it will work will be established within a month. The 76% of seats secured by left-wing and progressive forces may take up the reins and control the convention, establishing their own criteria for the command.

The Convention has members from Indigenous peoples who have been elected for reserved seats, such as Machi[3] Francisca Linconao. She is one of the people who has been criminalized by the Chilean state, and now she will help draft a new Constitution for the country. And she will do so along with other Mapuche women, who are engaged in a historic struggle to reclaim their lands, build a plurinational state[4], and achieve self-determination.

The most surprising outcome in these elections was achieved by “The List of the People,” who secured 27 seats with very limited campaign funds when compared to the millions of pesos invested by the right. “The List of the People” brings together several independents from territories across the country. The independent groups were challenged and criticized by the political establishment, but today nearly 70% of the Convention are independent members, who work in their communities and know Chile’s reality. They are Mapuche women, Indigenous people, environmentalists, people who live with chronic illnesses, feminists, and working people.

According to Chile’s Electoral Service data, only 41% of people who were eligible to vote actually voted in this election. The low turnout may be explained by the fact that the process was not largely publicized, polling places were changed at the last minute, and many people did not believe in change through institutional mechanisms. Social and political work beyond the boundaries of legalism is as valid and necessary as the work conducted to change the Constitution.

Where We Want To Go

With the latest elections, the historic process of change in Chile is moving forward. From the base, from residents’ associations, grassroots assemblies and working-class territories, organizations will be actively observing and monitoring the institutional and political process, which will help to strengthen grassroots work. There is a complex task to monitor and strengthen what members of the Convention propose and make sure there is unrestricted access to information.

It doesn’t take a constitutional lawyer to know the changes Chile needs. The people knows that. This new Constitution is expected to substantially improve the people’s quality of life in the future, once Chile makes sure to provide basic rights such as water, public education, health care, housing, and territories free from zones of sacrifice and violence. From feminism, there are demands to conduct profound changes to make sure life is free of violence, with a community care system and access to sexual and reproductive health care. In this process, the new Constitution must achieve a plurinational state and recover its natural wealth and basic public goods that have been removed by this extractivist and neoliberal Chile.

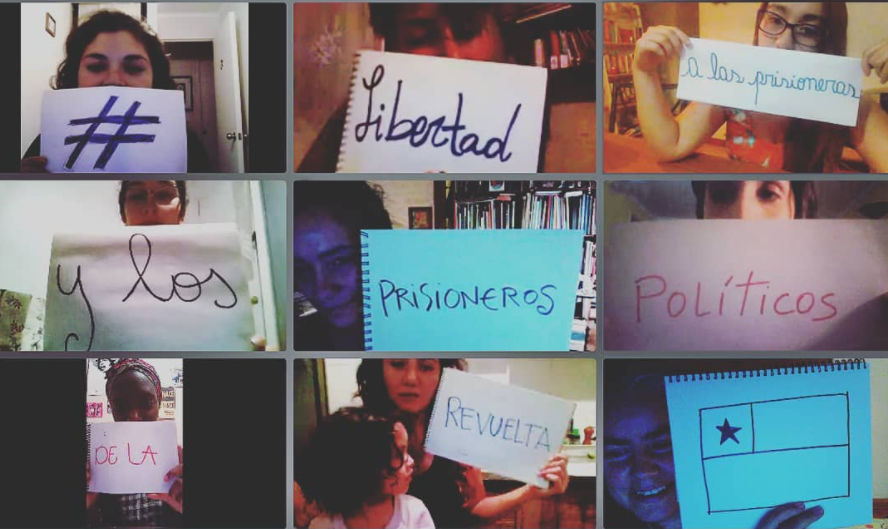

Chile is living a moment that was built through the continuing struggle of people out on the streets and communities, demanding real and structural change that can put an end to precarious living conditions. Let us not forget those who have died, been abused, mutilated, arrested. There are political prisoners from this uprising who have not even been entitled to a fair trial. Their freedom is part of the role of democratic change.

The creation of a new Constitution can be an opportunity to formulate a more participatory and democratic political and economic system. In Chile, this is all yet to be done, and facing this is a task for people who live and sustain their territories.

Danixa Navarro and Rocío Alorda are members of the World March of Women Chile. Danixa Navarro is a professor and holds a master’s degree in culture and gender theories. Rocío Alorda is a journalist and holds a master’s degree in political communication.

[1] No+ AFP [No More AFP] is a Chilean social movement which aims to put an end to the country’s current pension system. AFP is the Spanish acronym for Pension Fund Administrators.

[2] Wallmapu means “surrounding territory” in Mapudungun language, and it is the Mapuche name for the large area where Chile is located.

[3] Machi is how Mapuche communities call their religious authorities, healers, and advisors, who are also leaders defending their people, culture, and territories.

[4] “Plurinationalism” is a space (in this case, the state) where different peoples, nations, and ethnic groups live together respecting and acknowleding each other and promoting each other’s culture. Including plurinationalism in the new Constitution is a demand to promote the visibility of several peoples who live in different territories, as opposed to one restrictive national identity

.