We at Capire believe that grassroots feminist communication is necessarily a collective process, with a convergence strategy positioned in the dispute for hegemony and worldviews. Our political approach and the choices we make in communication are built in our vision as a grassroots movement, in our criticism of the system, and in our proposals of strategic alternatives. For this reason, the grassroots feminist communication is based on contextualized knowledge, on diversity, and on the feminist insurgence. And it is always in the plural, recognizing collective subjects, their times and complexities.

We view communication not as an instrument that is alien to our movements, but as something that is part of our politics, something based on it and built by it. The grassroots feminist communication in the World March of Women is guided, and at the same time built by a critical feminist, anti-racist, and anti-colonialist view intertwined with the anti-capitalist struggle. The choice of words, of platforms, of images and angles builds and expresses contextualized political subjects. This is why communication in our movements is not a task exclusive to specialists who perform a list of tasks, but rather it must be organic in our collective construction — it is a bottom-up process. A grassroots feminist communication may not be limited to the Internet and to the logics of social media. We need to bear in mind this perspective at all times in this digital capitalism age.

Communication in Digital Capitalism

Communication involves processes of production, distribution, and access to information. These processes, in our societies, happen mostly through a structure of concentrated ownership over communication infrastructures, communication means, and platforms. Communication has also been made through misinformation and fake news, which, although seeming to be a recent phenomenon, has been used against the left wing all over the world. These processes of communication also happen through data processing and extraction, being part of accumulation of data as capital.

Data are digital registrations of everything we do when are connected, or even when we move in cities increasingly monitored and with digitalized — transportation or health — services. These registrations are valued to the extent they are processed (classified, categorized, correlated…).

Datafication is the name given to the process of accumulation of data as capital. This is an effort to register, store, and process data about all life on the planet, guided by an extractivist and controlling logic, made possible by the structural, technical, and political conditions rooted in the financialized neoliberalism. Datafication is a technological convergence focused on data and on the capacity to progressively transform everything that is alive into a digital item (our personal and genetic data, the biodiversity, etc.), being capable of manipulating life on extreme scales. This process, thus, is not limited to Internet companies: data have increasingly becoming a production factor in a wide range of sectors, such as the health, trade, agribusiness, transportation, and insurance sectors.

It is necessary to denaturalize data. Data are not free in the environment, available to be collected. They are produced in our everyday life, in our relations and interactions, in our travels, when we purchase a good or do a research, etc. Datafication means extracting data from a large number of different sources, and, to make them massive, companies perform an active process of generation of new data. The sources used for data extraction include registrations of all financial transactions (payments, investments) and sensors spread across the most varied places and devices – whose names contain the adjective “smart”.

The “digital world” is organized around traps and structures of oppression.

In the first place, the so-called digital environment has a concrete basis composed of territories, bodies, and labor. Data do not exist in the void: they are generated by the interconnection of our lives, and they are extracted.

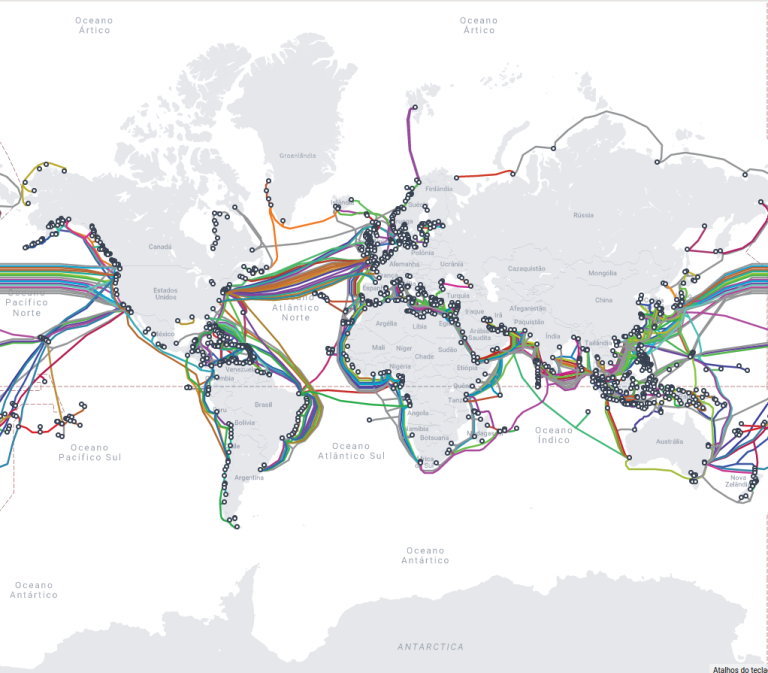

The maintenance of data storage and processing structures largely depends on energy consumption, and all batteries and devices traversed by the digital depend on mining activities. The so-called “cloud” is, in fact, a network of physical structures connected by cables, as shown in the illustration below:

This entire structure is controlled by big transnational companies. Accumulation of data as capital is a component of the corporate power machine. Such structure is also at the service of authoritarianism, vigilance, and blockades. Such dynamics is also called data colonialism.

Secondly, it is needless to say that Internet access is not an effectively guaranteed right. People have not the same Internet access around the world, and this issue is key when planning grassroots communication strategies.

Internet access is marked by huge inequalities between countries and within countries. DataReportal‘s report, for instance, shows that, while 97% of the population from North Europe have access to the Internet, this percentage is 42.2% in South Asia and 40.9% in West Africa. Internet access inequalities within countries are also significant especially if we take into consideration income, ethnicity, or location, that is, urban or rural.

But, if taken in isolation, the Internet access indicator may be tricky as well, since there are also big inequalities related to quality of connection and to what can be accessed. For example, in Brazil, the cheapest Internet packages of some carriers only allow for access to WhatsApp and Facebook. In other cases, the data package is not enough for the person to watch videos or participate in online meetings; or a person’s device might not have enough storage for applications; or, also, the country is subject to a blockade, such as is the case of Cuba, where comrades cannot participate in a Zoom meeting.

Therefore, we cannot say that all people have the same conditions of access and possibilities for using, creating, and accessing what is available on the Internet. These inequalities define our communication choices and exert an impact on our dynamics as a movement, within each country and also on the international level.

A third aspect is that the platforms and social networks are operated through algorithms. The intensive processing of our data allows companies such as Facebook to segment and direct content. They can offer increasingly “personalized” content, and an important share of the profits the company earns comes from that. Ads can be targeted to women of a certain age who live at a certain location and earn a certain income, who like and follow a certain topic (and so on).

When planning communications in social movements, we need to understand that visibility in social media is related to these dynamics of monetization and segmentation. So, often, some of us follow the page of our movement in a social media, but the movement’s content is never shown in our feed.

The creation of “bubbles” related to political views has to do with this corporate algorithmic process of social media. This process restricts our worldview and our diversity. And it keeps us trapped into the “bubble”. We need to face the naturalization of such corporate dominance and control in our lives, in our choices and information, and even in our desires. We at Capire have adopted a policy of not paying for ads, and this decision requires us to be more creative and organized so our content gets to our comrades and circulates beyond them.

How is the grassroots feminist communication positioned in such a dispute?

We see the grassroots feminist communication as a collective and permanent learning process. We base our actions on questions whose answers are not always the same.

How to build what we are going to communicate? Is the process of “doing communication” as important as the “product” of communication? How will we communicate and in what format? To define all this, it is crucial to understand the forms and the ways through which the people with whom we want to establish a communication have access to information. Do people use the Internet? Do they read? Do they listen to the radio? It is so important to be familiar with the different communication strategies and means already used by the movements at each location.

How can we express our political view and who we are in all of our communications? The challenge of this political expression is in the language, the images, the accents. And, particularly in these times when the cult of individualism prevails, our option is always to direct our words to the collective, to the collective subject built and represented by people.

One of the challenges of the grassroots feminist communication in building movements is that our diversity is not expressed only in the final product of communication (for instance, in a video), but in the very process of communicating. We say that “We are all communicators”, that communication is not owned by specialists, and that it is key to overcome hierarchies and the sexual division of the communicative labor. Much more important than the number of views or “likes” in a post are the effects and developments such content will have on the construction of the international grassroots feminism.

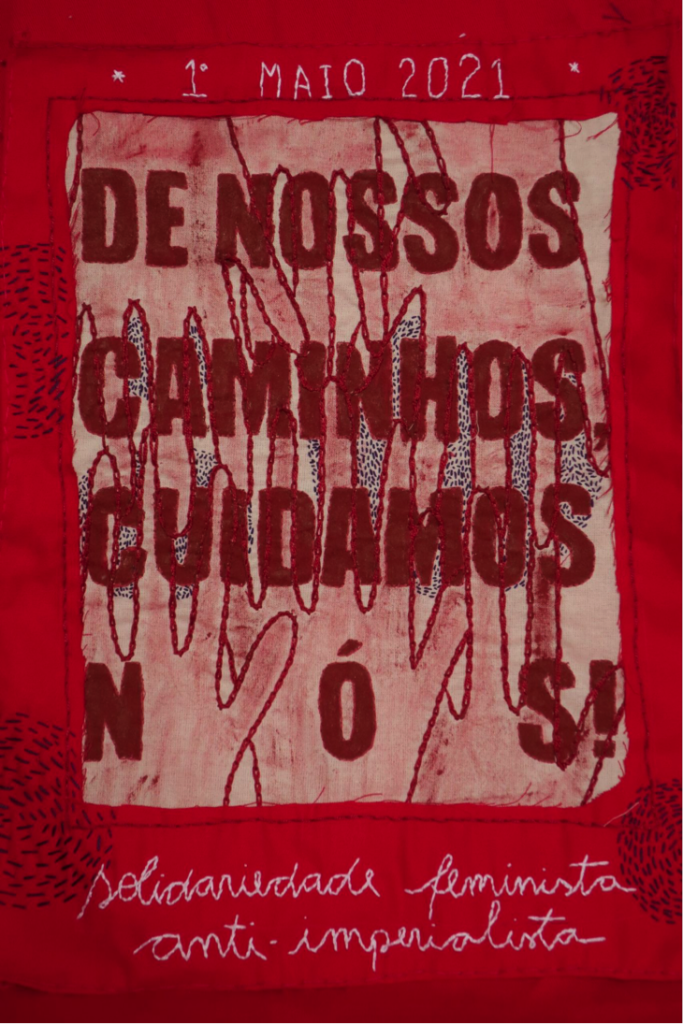

In 2021 we had a very beautiful example on Capire. For the launch of Capire, we published a text by Elpidia Moreno, member of the March in Cuba. Months later, we invited women from all over the world to produce and send feminist anti-imperialist posters. A young Brazilian militant woman embroidered a poster inspired by said text:

After reading the text of Elpidia Moreno on Capire, I could not get this line out of my head: ‘You all, friends of the world, can count on Cuban women. We will always be ready and willing to offer our efforts, our unconditional support to the just causes of the people’. I imagined hands that touched and transformed into an international network connected by the necessity to live without exploitation and violence, with freedom and will to impart wisdom without imperialist interference. The purple circles represent feminist militancy that bring possibilities to build another reality.

Renata Reis, World March of Women, Brazil

Finally, the grassroots feminist communication that faces digital capitalism has the challenge of building alliances with new political subjects that contribute to the technological sovereignty strategy. The grassroots feminism and the free software collectives may march together, struggling so that all — our bodies, territories, and technologies — be free.

Tica Moreno is a militant of the World March of Women and a member of Capire team. This text is an edition of the version published at magazine Brennpunkt.