Maamankhuu Sodnom is a herder from Tsogttsetsii soum, Umnugobi province, Mongolia. She lives in a small community place called Mandakh and has been herding for over 60 years. She is the head of the Mongolian Gobi Nomadic Herders’ Association and the regional coordinator for Central and East Asia of the World Alliance of Mobile Indigenous People (WAMIP). WAMIP is a key organization for the 3rd Nyéléni Global Forum, that will happen in Sri Lanka this September 2025 and will bring together international grassroots organizations from around the world to discuss the system of oppression and the people’s alternatives for a systemic transformation.

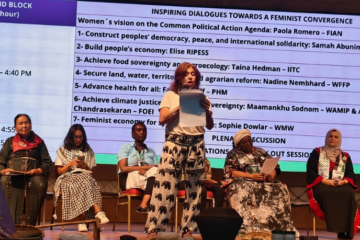

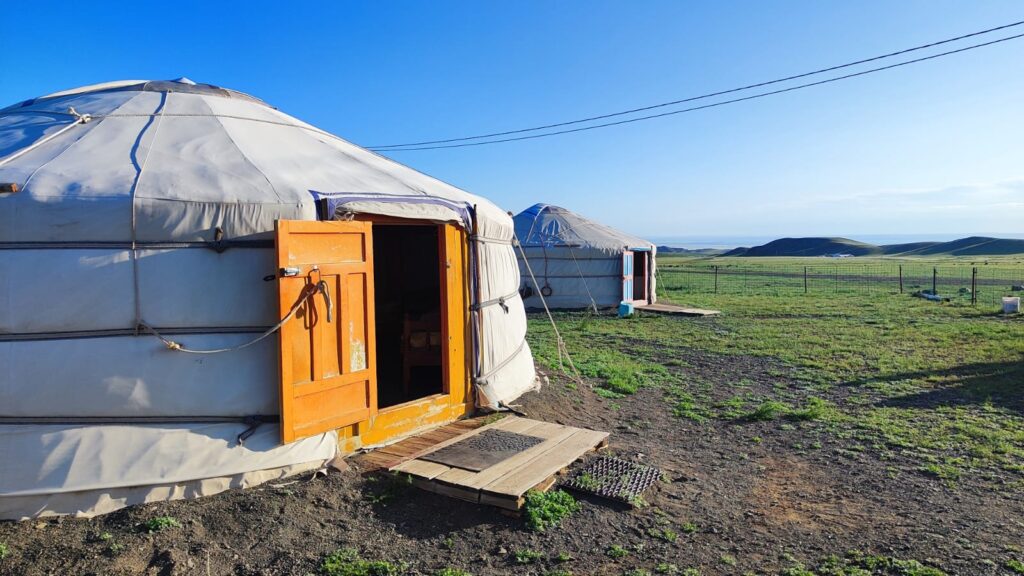

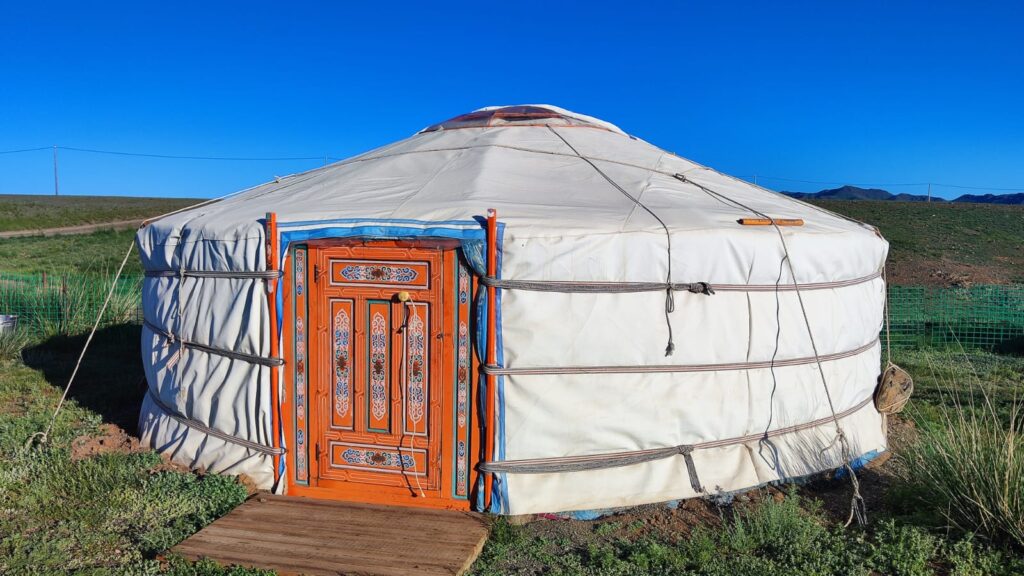

This article is an edit of an interview given by Maamnkhuu during the activity “Empowering Herder Women: Challenges, Solutions and Opportunities” organized by the World March of Women (WMW) in partnership with WAMIP and the Association. This event took place in the end of June, and it was part of the 6th International Action of the WMW calendar. During the event, “over 150 women gathered in Mongolia’s Gobi region to address critical challenges faced by pastoralist women, particularly those related to mining and pastureland management”.

The country rich in coal, copper, and other important raw-materials for the tech industry has been historically struggling against the impacts of mining for local communities and for the uplift of traditional and indigenous forms of living, often ignored in the so-called process of modernization. In the article below, Maamnkhuu describes her history in the movement, the historical context and the current struggles.

During the Soviet Union, we had community groups who were assigned to work together to meet the requirements set by the government, and I was very active in my community. After the transition to the market and democratic society, we decided to have some of those practices, so I created a new community group called Oyud. We were working as a team with the other herders. Then I was invited to attend an international conference in Nairobi, Kenya, on nomadism and herding. They asked me to give a speech, where I highlighted that the herders in Mongolia are just left in their small town, and no one even knows that they exist and that they have a problem. After that, I was approached by a person from Iran to talk about those issues. This work continued, and in 2007, in Spain, the World Alliance for Mobile and Indigenous People was established. That was the beginning of our international work.

This first congress held in Segovia, Spain, was very unique. We brought our traditional equipments that we usually use while herding. A person from Spain brought their animals to the center and went to the government palace with them, but it wasn’t that easy to have the international impact and accreditation. 32 country representatives participated, and we had participatory activities. It was a very meaningful event, where we identified key challenges from the places we came from. One of the key issues is about women herders, particularly in Mongolia, whose labor is never valued and all the work is accredited to men. So that was the biggest issue: how we can identify the challenges and opportunities to make sure that the women and men herders are equally valued, and how we can identify the opportunities for care economy that is put on top of women herder’s shoulders.

Following the event of 2007, there was a big event held in India. In there we held the first women herders conference and dialogue. After these discussions, I came back to Mongolia and decided that we should have an own organization that can represent particularly women herders. That’s how the Mongolian Gobi Nomadic Herders’ Association was established in 2014. We wanted to do the work with or without the international support, so it was more of a locally driven action.

Our first action was to support one of those politicians who ran for the member of parliament. When he was elected, it gave us an opportunity to reach the Ministry of Agriculture and bring them to our hometown to explain our concerns, challenges and the opportunities we have.

Thanks to this collaboration with the Ministry of Agriculture, we submitted our recommendations also had in-person discussions with policymakers at the ministry level. We gave them a list of 1,000 professions which usually herders do on a daily basis. That’s how we could identify herders as the holders of 1,000 professional qualifications. Based on that, the Ministry decided to give every herder in the nation a certificate recognizing that they are the holders of those professions and accepting herding as a profession. There were other requests and policy recommendations too. For example, we also asked them to identify elder herders as trainers and certify them, to use their indigenous knowledge and to make sure that the elders are also involved in the formation of the next generations. But that wasn’t accepted by the Ministry.

Current concerns

Given the fact that mining is typically linked with economic growth, I’d like to highlight that almost 80% of the nation’s economy is dependent on our land, particularly the place where we held the women herders’ discussion. This is also one of the key issues we want to address through our actions and the events and other policy recommendations.

Herders have been used as election tools for the politicians to have their votes. So they care more about us during the election period or election year, and then they just leave us. It’s very concerning how the herders have been used for political purposes. In election time, there will be a lot of conferences and policy discussions. At national and local level, regardless of if it’s national or local, they usually never give a seat to herders. They never allow the herders to speak. It’s only the elite or the politicians or the power holders who often speak. We have a limited space for expressing ourselves.

I’m very proud that the Mongolian women, particularly women herders, are very strong and very brave. In terms of social, political and economic life in Mongolia, almost 70% of the work is on women’s shoulders. That’s why they don’t want to support us and invest in us. They want to keep us silent and there is a lot of pressure on women’s shoulders, but we don’t want that. There are some NGOs that usually try to influence our work too. It’s a kind of usual thing, which gives us the message of how they see the herders, particularly the women herders, as weak, and they try to oppress. We are happy to collaborate with the NGOs, but they usually use our knowledge and our system, more for their own benefit rather than for mutual benefits.

Other concern is regarding the elders, and the older herder’ indigenous knowledge. It’s been a while that this knowledge isn’t considered, accepted or passed through to the younger generations. That’s why women from Inner Mongolia came to the WMW and WAMIP event to show how they are getting their indigenous knowledge from their older generations and passing through, developing it and making sure it will be passed to the next generation.

I would like to thank the World March of Women for making this possible. It has been a hard time for us to be brave and to have a platform and space to speak as women herders. As a final remark, I’d like to ask the World March of Women to give more attention to educating women herders and helping them to develop personally and professionally and to understand and see herding as a profession and think how to improve it. Also educating the herders to help them understand the importance of the wisdom coming from the older generations and older people and passing it to the next generation. We need to collaborate on educating our herders and to making sure that all the wisdom and traditions are passed to the next generations.

Photos taken by Sibel Tekin during the “Empowering Herder Women” activity