It was September 2020, and I was listening to the radio while doing household chores. It had been seven months since the pandemic started. Radio Hala Bedi Irratia was playing the show “Suelta la Olla” (“Put Down the Pan”). They announced you would be interview: now on our show, Sarah Spatz will talk about what is happening in El Infierno, a neighborhood in Donostia, Basque Country.

I started to listen to you, and was mesmerized by the interview, mesmerized by your account, by the power you conveyed and your unequivocal denunciation of racism. I stopped what I was doing just to listen to you speak, Sarah.

In half an hour, you reviewed all the racism experienced in this country. You denounced the criminalization and stigmatization experienced by people who live in squats, police brutality, the authorities’ propaganda strategy to vilify the people who lived in El Infierno and prevent society from sympathizing with them. You criticized the Donostia city government for not being concerned about improving people’s conditions and for being ready to displace them and sign contracts with the real estate industry. You denounced the “Gag Law” that bans people from recording bad police conduct, and said that it only goes to show how not transparent institutions are. You spoke about the racial division of labor, the work that we, migrants, do, that white people don’t.

Every day the police give migrants, Black people, and people from an Arabic background a racist treatment, forcing them to lie down on the factory floor in Infierno. People who were there and spoke Castilian or had documents—including two Europeans—were allowed to stand, arms behind their backs, while they waited to be released. Meanwhile, racialized people were treated like criminals. You said, “Can’t white Europeans be criminals too?”

I really liked your appeal to engage society as well, even though I’m not really sure that’s the way to go. But I also believe in solidarity and empathy with groups who don’t share the same privileges.

I remember your words: “They’re coming after us today, they will come after you tomorrow, this will only become worse…”

After the interview, I only knew what you said about who you were: Brazilian, living in a squat in the Infierno neighborhood, in Donostia-San Sebastián. You had documents as a refugee, you had to leave Brazil because, as a trans woman and activist, the right tried to kill you.

When the show was over, I messaged Kátia, my Brazilian friend who lives in Donostia. I asked her about you, but she could not find your contact information. Then I eventually forgot about you…

When the radio show was published on the Hala Bedi website, I thought there could be a picture of you, but there wasn’t. I wish I could have met you, could have heard you close. Maybe that’s asking too much, but I wish I could have shared activism with you, because I also believe those of us who have privileges and conditions, even if they’re not much, must use them to support the people who don’t.

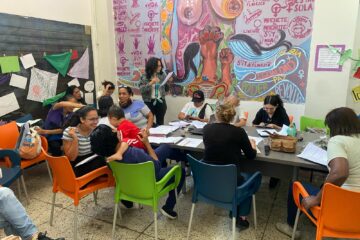

Three years later, it’s 2023, and we at the Network of Migrant and Racialized Women in the Basque Country [Red de Mujeres Migradas y Racializadas de Euskal Herria] were invited to take part in state activities in celebration of 40 years of the occupied area. We were not on the front line occupying these spaces, we got there later, to the Kartzela Zaharra in the city of Bergara, to the Txarraska, in Basauri… We don’t have our own space. How can we be part of these activities if we don’t have the privilege to occupy them? If these are still spaces for white people?

That was when you came back to my mind, because you were there, in the squats, you were the one that should have been there for that activity. I called Kátia, I asked her to look for you, to not give up. Two days later, she texted me: “Lu, Sarah passed away a year ago.” I froze, I felt sad. Even though I had never met you, I felt a pain in my chest.

We know that’s life, that we all must go, but I hoped to meet you, and hoped you could meet my sisters with the network: Ceci, Fer, Karla, Leo, Vane, Flavia, Judith, Zarys, Mabel, Aura, and Maria. I wish I knew what haircut you had, what your mouth looked like, the shape of your face… Did you look like Kátia or Sônia, my two Brazilian friends?

I can’t picture a specific body, as our territories are so diverse, it is impossible to imagine it.

But, finally, I would like to say that you touched my heart, because, like the Brazilian poet Cora Coralina wrote,

I don’t know… If life is short

Or too long for us,

But I do know that nothing we experience

Has meaning if we don’t touch people’s hearts.

May you rest in peace, Sarah. Wherever you are, you live in us.

Sarah Spatz was a trans Brazilian migrant. An activist who moved to Donostia, Basque Country, where the El Infierno squat became her home in 2020. She passed away in November 2021. There was no autopsy, because she tested positive for COVID-19.

Luciana Alfaro is Peruvian and lives in the Basque Country. She is a member of the World March of Women International Committee representing Europe, and a member of the Network of Migrant and Racialized Women in the Basque Country.